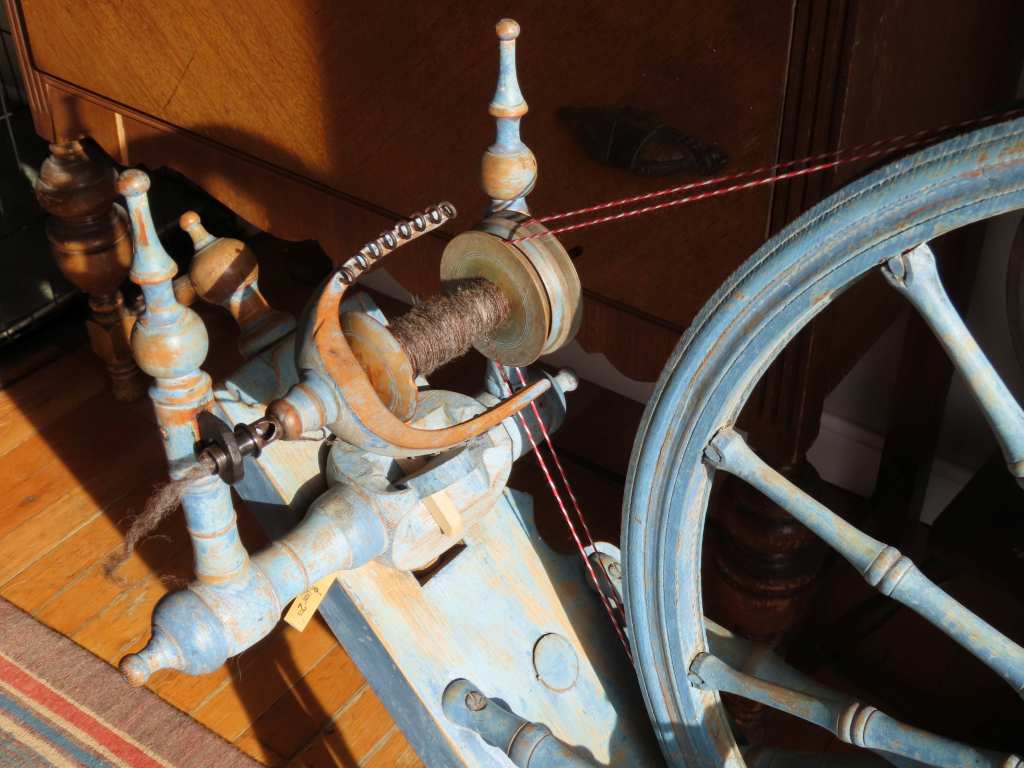

This robin-egg-blue Norwegian wheel is (to borrow from Max Verstappen) simply lovely. As with the OAP wheels in the previous post, this style comes up for sale with some regularity in the US midwest and even Canada.

In fact, the man I bought this wheel from had found it in Ontario, where he said they called them “crowder” wheels. I have not heard that name before, but wonder if it refers to the compact footprint designed to fit in crowded spaces. Just speculation …

The nickname I am familiar with is “BESS,” from the antique spinning wheel folks at Ravelry. “BESS” is an acronym for “Black Earth Super Slanty.” The “Super Slanty” describes the shape–an extremely slanted table with legs protruding from the table end (not bottom) following the same angle as the table. “Black Earth” refers to a photo taken in Black Earth Wisconsin around 1873 of five women in the Rustebakke family. The matriarch, Siri, sits in the middle with hand carders in her lap. Four younger women surround her (likely three daughters and a daughter-in-law), all posed with spinning wheels in front of them. The spinning wheels, each meticulously angled in a way that highlights their elegant style, are what make the photograph so captivating. I wanted to include the photograph in this post, but the Wisconsin Historical Society, which owns rights to the photo, charges too much for me to reproduce it here. ***For my rant about these charges, see below*** Although I cannot post it here, the photo (and a second one that include’s Siri’s husband and a dog) is easily found by doing a search for “Siri Rustebakke.”

What is significant about the Black Earth photo is that all the Rustebakke women are using the same style wheel. Were they all brought from Norway, were they built in the US based on a Norwegian style, or both? The answer remains unclear. The Rustebakke family came from the Valdres area of Norway and evidence shows this style wheel in that area. The Valdres Folkemuseum has several of them in its collection.

The Vesterheim Norwegian American Museum in Iowa also has examples in its collection with “Valdres” frequently appearing in the wheel description (thank you A. Myklebust for this information). Many families from Valdres also settled in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin, about 12 miles from Black Earth, and one of these wheels shows up in this postcard from “Little Norway,” a living museum, there.

Patricia and Victor Hilts, in their article about Wisconsin spinning wheels suggest that the wheel at Little Norway may actually have been one of the Rustebakke family wheels. Hilts, p. 19, fn. 86. The Hilts also speculate that these wheels may have been made in Wisconsin rather than Norway. Hilts, pp. 18-19.

They note that some wheels have maker’s initials of “JS” and that there was a furniture maker named Jacob Schanel advertising in the area. An absolutely fascinating piece in the book “Creators, Collectors, Communities,” discusses Aslak Olsen Lie, a furniture maker from Valdres, who immigrated to Blue Mounds and continued to make furniture in a meld of traditional Norwegian and American popular style. link here (I could not help but notice the robins-egg-blue paint on the back of Lie’s cupboard).

While these furniture makers could also have been making wheels, there is no evidence showing that they did, as far as I know.

We do know, however, that spinning wheels were made in Valdres. A Wisconsin settler, A. O. Eidsmoe, wrote: “I was born in Southern Aurdal in Valders, Norway, the 13th of February, 1814. My first or earlier childhood years passed without anything of importance.

Our parents were poor and with six children (three boys and three girls) were able to make both ends meet, nothing more. As soon as we were old enough, we had to go to work. We boys learned to run a turning lathe and made tynneturer, lobbismarer, peppergrinders, rolling pins, distaffs, and as we learned the trade, we commenced to make spinning wheels.” The Norwegian Settler’s Story.

Perhaps the best evidence that these wheels were made in Norway is that they turn up for sale there. I was delighted to see this recent beauty on Facebook Marketplace for sale in, not surprisingly, Aurdal, Valdres.

While some have makers’ initials, most seem to be unmarked. It seems likely that, in a pattern typical for many regions of Norway, Finland, and Sweden, Valdres used its abundant water power for furniture and spinning wheel production and there were multiple makers in the area, all producing the same regional style wheel. If that was the case (and it’s purely speculation at this point) it is very possible that one or more of these makers continued to make this style wheel after immigrating to the midwest.

Whether all were made in Norway, or some made here, there do seem be be multiple makers and individual differences between the wheels. Some have fancier turnings and some have internal cranks, for example. But all share certain characteristics. The spokes and legs are turned to resemble bamboo–a style found in late 18th and 19th century furniture, but uncommon in spinning wheels.

A cross brace between the two downhill legs gives stability to the highly slanted table,

as do the screwed-in struts.

The table itself is adorned with a decorative swirled edge on the non-spinner tension end

and subtle shaping on the other end.

The MOA has a nifty sliding mechanism,

with nicely scooped edges,

for precise adjustment of the drive band angle. It also allows the spinner to easily use different-sized flyers for wool and flax.

The treadle is very wide,

working equally well for one- or two-footed treadling.

The flyer on mine is a generous size,

with a relatively large orifice.

The leather flyer bearings are cut flush with the maidens on the backside.

Unlike many Norwegian wheels, the whorl turns righty-loosey.

The the bobbin whorl

neatly nests into the flyer whorl, a feature found on other styles of Norwegian wheels.

Mine is a good spinner, although it required quite a bit of initial adjustment to properly align the whorl.

The spokes, which have fat pegs holding them to the rim, are loosey-goosey along the hub, with lots of play.

The original hardware keeping the axle ends in place was replaced with clunkier modern hardware, which, while not particularly attractive, works well.

With a little shimming of the rear axle, some leather washers, and a clarinet reed under the MOA,

everything aligned eventually and she became a pleasure to spin. And, I have to say, I enjoy just looking at her–such a sublime color. These wheels were often painted, sometimes in multiple colors. I believe that the blue paint on my wheel is original, but there are traces of red highlights, too, which have worn off.

Interestingly, as with some of my other Norwegian wheels, the paint strokes are visible in some areas–it looks like a fast and not-very-meticulous paint job.

But it has lasted for well over a hundred years and makes this wheel especially visually satisfying to me. Combine it with the design features–not too cluttered, clean lines, elegant stance, rounded yet restrained turnings–it is like a sculpture in motion.

References:

Amund O. Eisdmoe’s “Story of His Own Life” is found in “The Norwegian Settlers Story” in the online Norway Heritage–Hands Across the Sea, link here

Hilts, Patricia and Victor, “Not For Pioneers Only: The Story of Wisconsin’s Spinning Wheels,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Volume 66, #1, Autumn 1982.

Thorlow, Peter, “Aslak Lie Cupboard,” Creators, Creators, Collectors, edited by Ann Smart Martin, Mount Horeb Area Historical Society and UW Madison, 2017. Available online through Creative Commons.

*** I been writing these blog posts for years now and, in doing my research, have been fortunate to deal with a wide variety of generous people and institutions. Most are curious and enthusiastic people who share my love of trying to unravel the history of objects and pass it on to others. In writing posts, I do my best to abide by copyrights, to ask permission to use material, and to properly attribute photographs, research, and quotations. When I contacted the Wisconsin Historical Society for permission to include the two Rustebakke family photographs in this post, I found the fee to post each photograph (special non-profit rate!) was $20, for a total of $40. This is the first time I have ever been asked to pay a fee to use a photograph–other places have simply requested attribution. I fully understand that it costs money to collect, maintain, and digitize a collection and would have no objection to paying a small fee. But $40? I could rescue a wheel for that.

I gladly contribute to small historical societies manned by volunteers and struggling to keep their doors open. But, this historical society (according to its website) has an annual budget of over $35 million dollars, well over 100 paid employees, and is building a $160 million dollar history center. It does not need to charge such high fees for use of its photographs, especially when the user, like me, is unpaid, and making no profit whatsoever from use of the photographs. Such a charge seems outdated in the internet age and a frustrating impediment to further sharing the story of the Rustebakkes and their spinning wheels. Making history accessible to all and connecting people to the past through collecting, preserving, and sharing stories is part of the Society’s mission and vision. They missed an opportunity to do that here.***