Most wheel makers remain a mystery. Even when they mark their wheels, leaving names or initials, it can be difficult to determine who they were or to find any details about their lives.

That is not the case with Marlboro (or Marlborough) Packard. He marked his wheels and lived in a town–Union, Maine–with an unusually well-documented history, allowing us to get a small glimpse into his life.

Marlboro was born in 1763 in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. According to DAR records, he served as a private in the Massachusetts militia during the Revolutionary War. At some point after that, he moved to Maine, joining his uncles, Micah and Benjamin, who had been there as early as the 1770s.

His uncle, Benjamin, in fact, has a role in Union’s early history. Initially called Stirlingtown, Union was born in controversy. A group of Scottish men first claimed possession but, soon after, a Massachusetts man, Dr. John Taylor, bought the land, despite the previous claims. After some dispute, Taylor prevailed, and in 1775, Marlboro’s uncle, Benjamin, worked with Taylor’s indentured servants to clear the land and cut lumber for Taylor. History of Union, Maine, pp. 27-39.

That year, Benjamin Packard built the first permanent house, a log cabin, in what would become Union. The next spring, in 1776, the Robbins family moved into the cabin and their story was the basis for the novel “Come Spring.” The foundation of the house built by Benjamin is still intact near the shore of Union’s Seven Tree Pond.

It’s unclear whether Marlboro came to Maine right after serving in the militia, but the 1790 census shows that, by then, he had joined his uncles, living in Cushing on the coast. That same year, he married Mary Ann “Nancy” Blackington. They had seven children, all of whom lived to adulthood–no small feat in those days. According to his children’s birth records, Marlboro appears to have been living in Union in the early 1790s, then moved to nearby Warren and Thomaston, and eventually returned to Union by 1803.

He lived the rest of his life in Union, on a farm on Clarry Hill, at times serving the town in positions such as selectman. He died in 1846, days shy of his 83rd birthday. Marlboro’s descendants still live in and around Union. His oldest son, Nathan, named his first son (born in 1828) “Marlboro.” This namesake grandson became a well-known master shipbuilder in Searsport, Maine, clearly inheriting his grandfather’s design and woodworking skills. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marlboro_Packard.

As noted in the previous post about Marlboro’s flax wheels, “Clarry,” his wheels are well-designed and attractive. And, as with his flax wheels, Marlboro’s great wheels are immediately recognizable as his.

He used a double-nut tensioning system–a somewhat unusual design found primarily in wheels from New England and New York. The wheels are sturdy, with some lovely turnings and scribe marks, and his signature “MP” stamps.

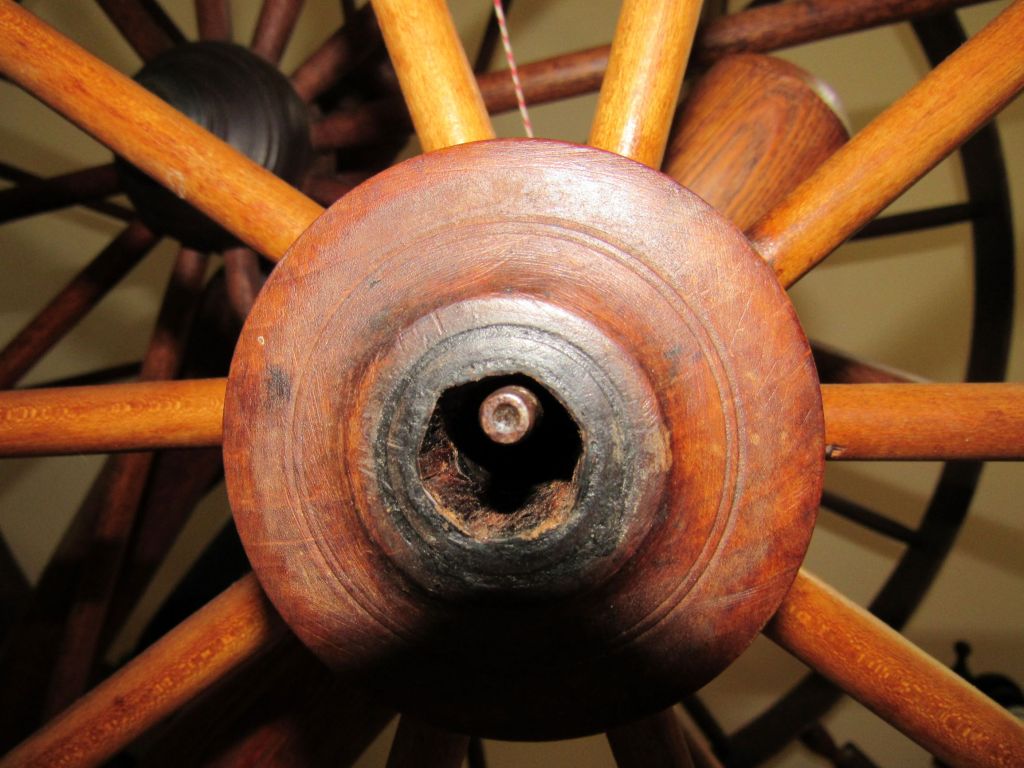

The hub is particularly nice, with brass bearings in both ends.

The axle has square base, holding the wheel away from the upright, and nuts to tighten down each end.

My wheel originally came with a Miner’s head, but I replaced it with an old bat head, new spindle, and new cornhusk spindle bearings.

As with his flax wheels, Marlboro’s great wheels show no influence from the Shakers. For example, the top of the spindle support is hefty–flat, wide, and collar-less–in contrast with Shaker wheels, which generally have slender, curving uprights with a collar.

Interestingly, a few wheels have turned up that look almost identical to Packard’s, but with the initials “MS.” It is not known whether MS may have worked with Marlboro, copied him (or the other way around), or whether the similarity is coincidental.

Thanks to some friends who spotted her, I found my great wheel in the front window of an antique store in Liberty, Maine, two towns away from Union, where it had been sitting for a long time.

According to the store owner, it had belonged to a Liberty woman, Ida Quigg McLain, who lived in a old square farmhouse with a huge central chimney.

Whether that chimney is responsible, I’ll never know, but the spinner side of the wheel is badly blackened and charred,

likely from being too close to an open fire or hot stove.

The charring doesn’t affect the wheel’s spinning, though. She spins beautifully and I love that she’s a local girl—made from trees one ridge over from where I now live, by a man with one of my all-time favorite names—Marlboro Packard.

For more on Marlboro Packard and the history of Union, see the previous post “Clarry,” and these books:

Sibley, John Langdon, History of Union, Maine, originally published in 1851, reprinted by New England History Press, Somersworth, N.H, 1987.

Williams, Ben Ames, Come Spring, Houghton, Mifflin Co., Boston, 1940.

Update December 2020: Last month I picked up a Packard great wheel in Nobleboro, a nearby town, for my friend, Susanne. The seller had found the wheel at the Waldoboro dump. Its drive wheel did not appear to be original, but the rest of the wheel was lovely and had some interesting differences with my wheel. My wheel is on the left in the photo below.

Susanne’s wheel had a slightly daintier feel than mine. The tension screw supports were smaller overall and fit up snugly against the table–in contrast to mine and another wheel of Susanne’s, which have a significant gap between the supports and the table.

In addition, the ball at the top of the wheel post is flatter on Susanne’s than on mine.

The legs are much the same.

Intriguingly, Susanne’s wheel had a “VII” inscribed on the table, the front tension screw support and the wheel post–something I have not seen on other Packard wheels.

It is hard to say whether the numbers were for disassembling the wheel for transport, used because apprentices or others were helping with assembly, or for some other reason.

It would be interesting to know whether Marlboro Packard changed his wheels slightly over the decades of production or whether he changed things up from wheel to wheel. It was a treat to be able to compare these wheels side by side.