While many Finnish wheels found in North America, including those in the two previous posts, likely were made in the 1900s, occasionally some older ones come along.

This curvaceous green beauty, which I found in Pennsylvania, was probably made in the mid- to late-1800s.

There does not seem to be any dispute that this style wheel, with its distinctive treadle design and abundant curves, is Finnish, but its specific origin remains unclear.

One advertisement, with a wheel marked 1855, indicated that the wheel was from the southeast coast of Finland, but I have not been able to confirm that.

Although several of these wheels have been posted on the Finnish Rukkitaivas Facebook group, so far, as far as I know, no one has identified a maker or region where they were made.

As with many other Finnish wheels, these wheels have double arched uprights and treadles set into the treadle bar, rather than pivoting from the legs.

On mine, there are metal pins attaching the uprights to the arch, on the spinner-side only.

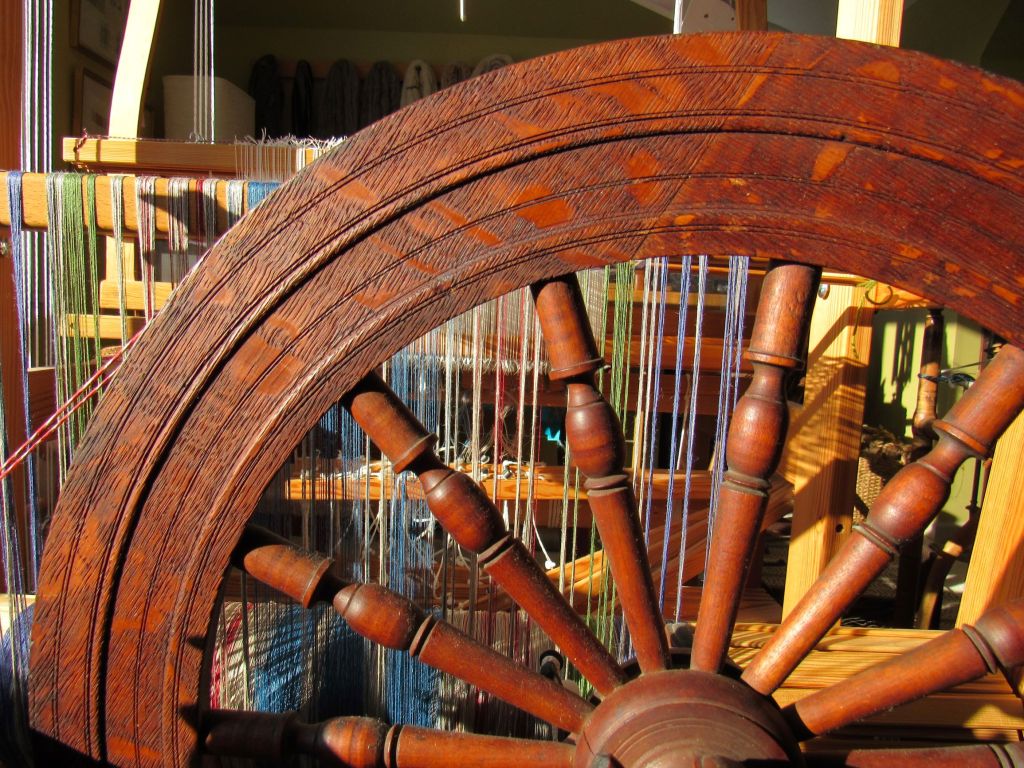

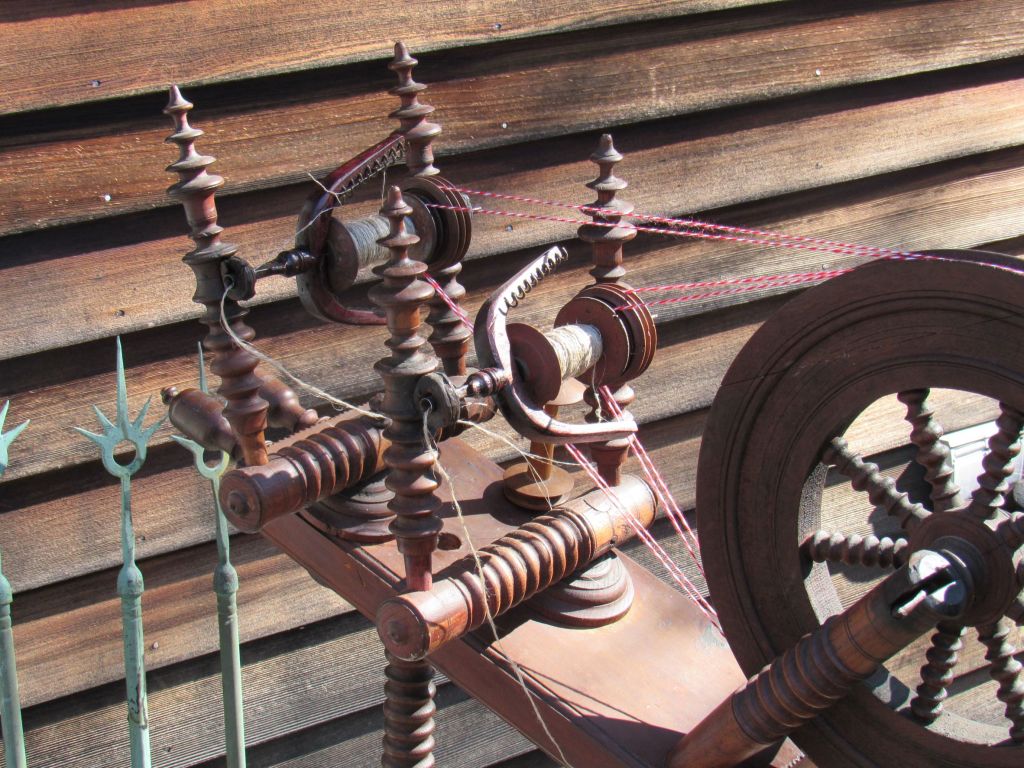

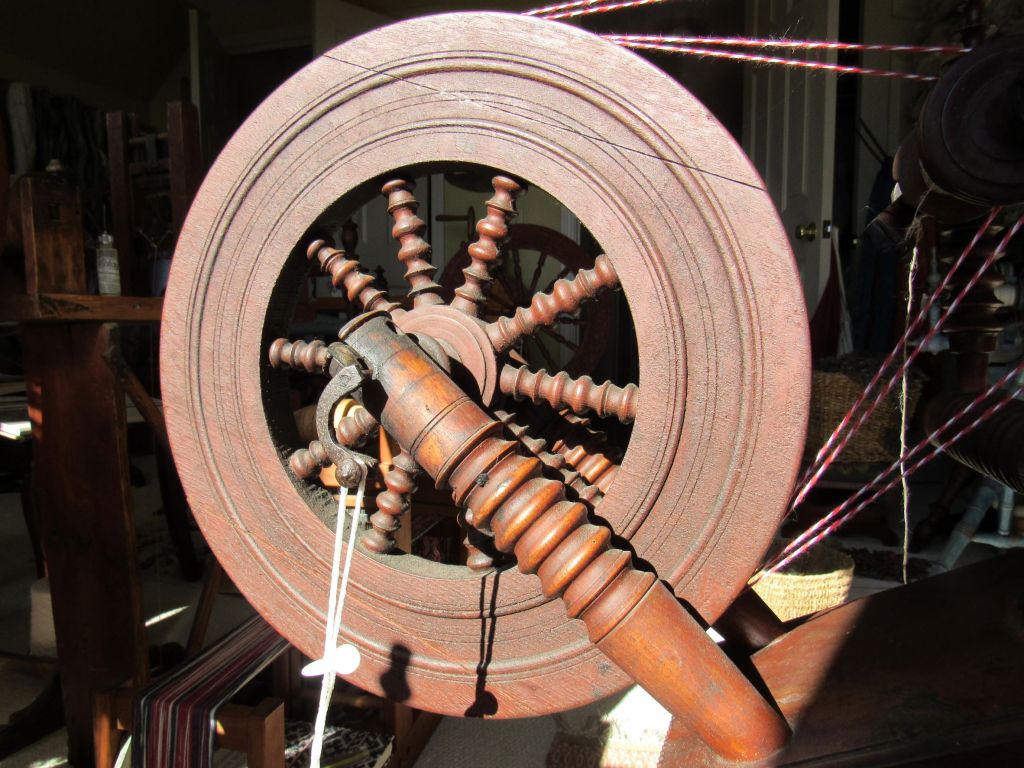

The drive wheels have from 16 to 20 delicate-looking spokes, giving them an almost spider-web look.

What makes these wheels stand out most, however, is the overall curvaceousness.

From the bulbous mother-of-all and legs

to the swooping treadle triangle embellished with curls,

there is not a straight line to be seen.

Even the tension knob looks pregnant.

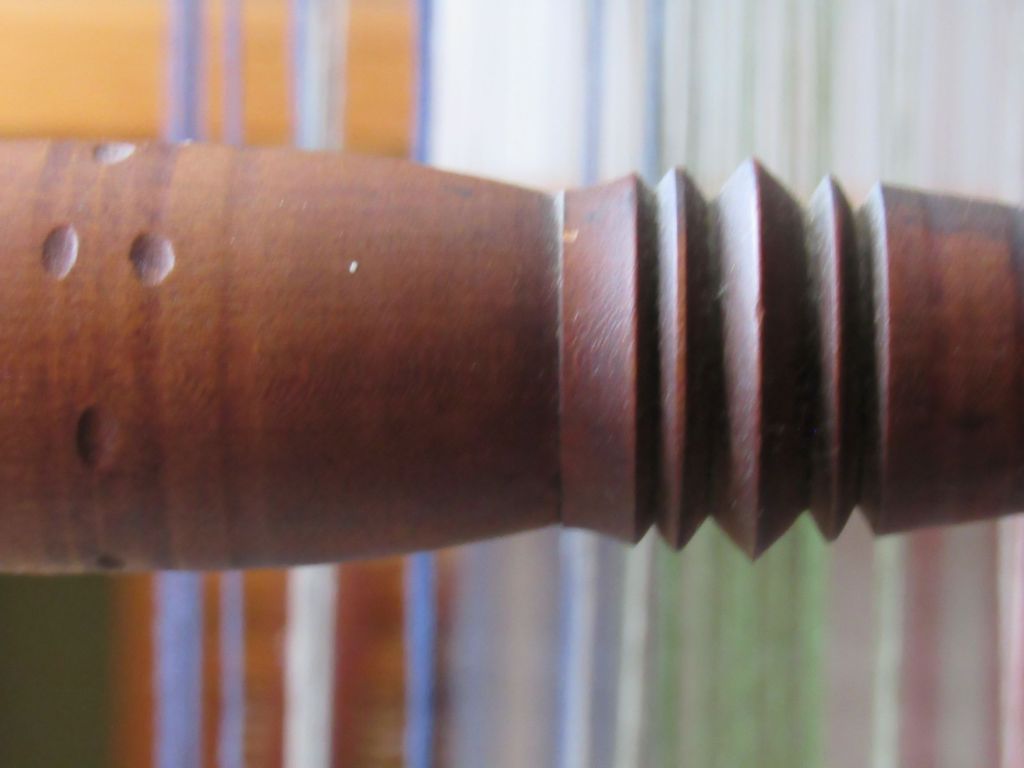

The treadle itself is an unusual exaggerated shape,

with chamfered edges underneath.

The sculptured treadle pad is set into a base with mortise and tenon joints.

That base, which has the treadle pins, is then set into the spinner-side treadle bar, which extends between the legs.

The recess for the tension-end treadle pin is supposed to have a small wooden piece and wooden pin, covering the treadle pin, which on my wheel is missing.

Curved bars run between all of the legs, with the feet set into the corners.

While most of the dozen or so photos I have seen of this style wheel closely resemble Tuulikki, there are some variations. The 20-spoke wheels seem to be a little larger than those with 16 spokes and have metal wires running from the table to the wheel uprights, similar to those on Impi, in the previous post.

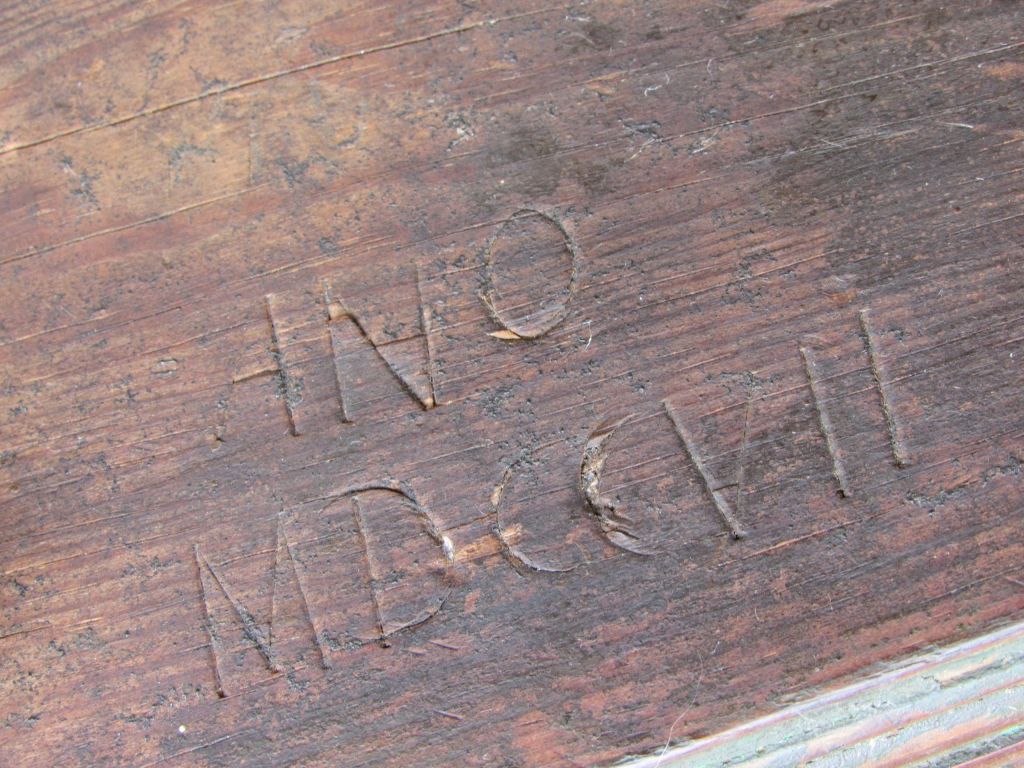

Most are painted, including the underside. Some have painted dates or initials, and some are slightly more embellished. I suspect they were all made by the same wheel maker, or perhaps a family of wheel makers, but, on the other hand, this could have been a regional style used by several wheel makers.

As with most wheels from the mid-1800s, Tuulikki has seen a lot of use. The wear on the treadle is interesting. The treadle bar is very worn down, with two concave areas (more pronounced on the right side).

Where the treadle meets the bar, there is little wear, with wear showing again on the treadle before the swoop. It could be that the treadle is a replacement, but I have seen other wheels with a similar wear pattern. Interestingly, this Finnish treadle design creates a pivot of two pieces of wood that tends to pinch the foot when spinning barefoot. Which leads me to wonder if it was unusual to spin barefoot in Finland. On this wheel, the wear pattern could be explained by a spinner wearing shoes or boots with small heels neatly resting on the treadle bar, with an instep high enough to span the pinch-zone–an area with no wear–and then wear again where the ball of the foot rested on the treadle.

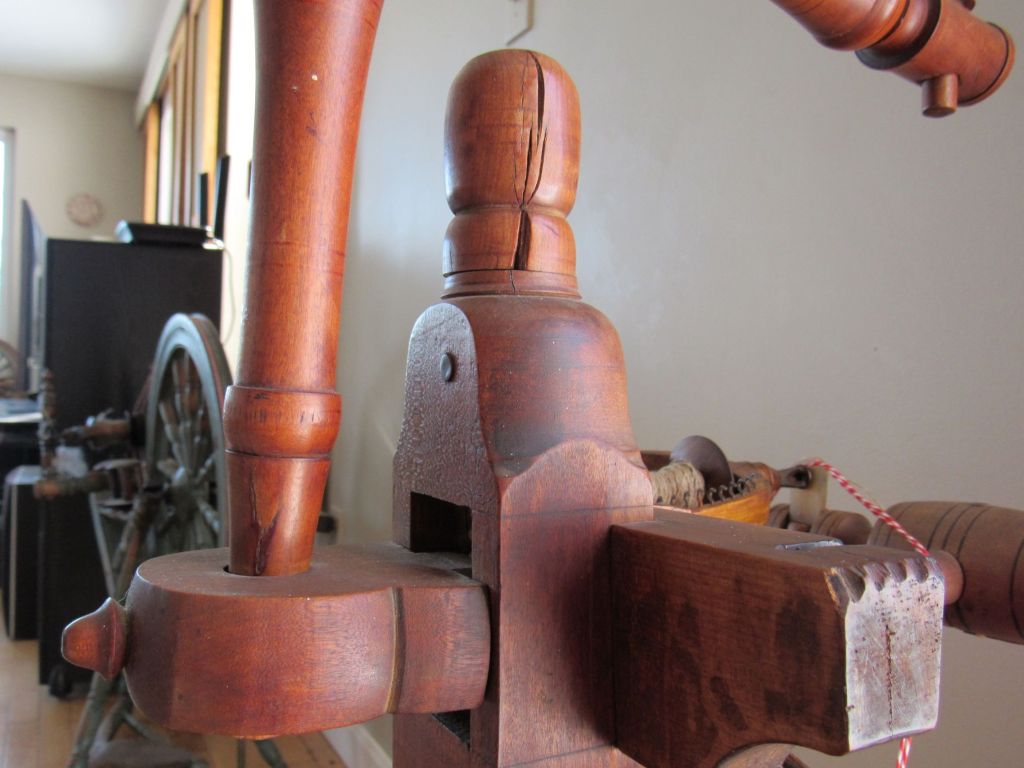

In any case, there is no question that this wheel was heavily used. There was one large shim on an upright when I bought it.

Closer inspection showed that every upright was heavily shimmed in the past–all broken off through time.

I have placed two clarinet reed shims of my own.

There is paper shimming under the collar and multiple pegs in the maidens,

all designed to keep the wheel tight and in working order.

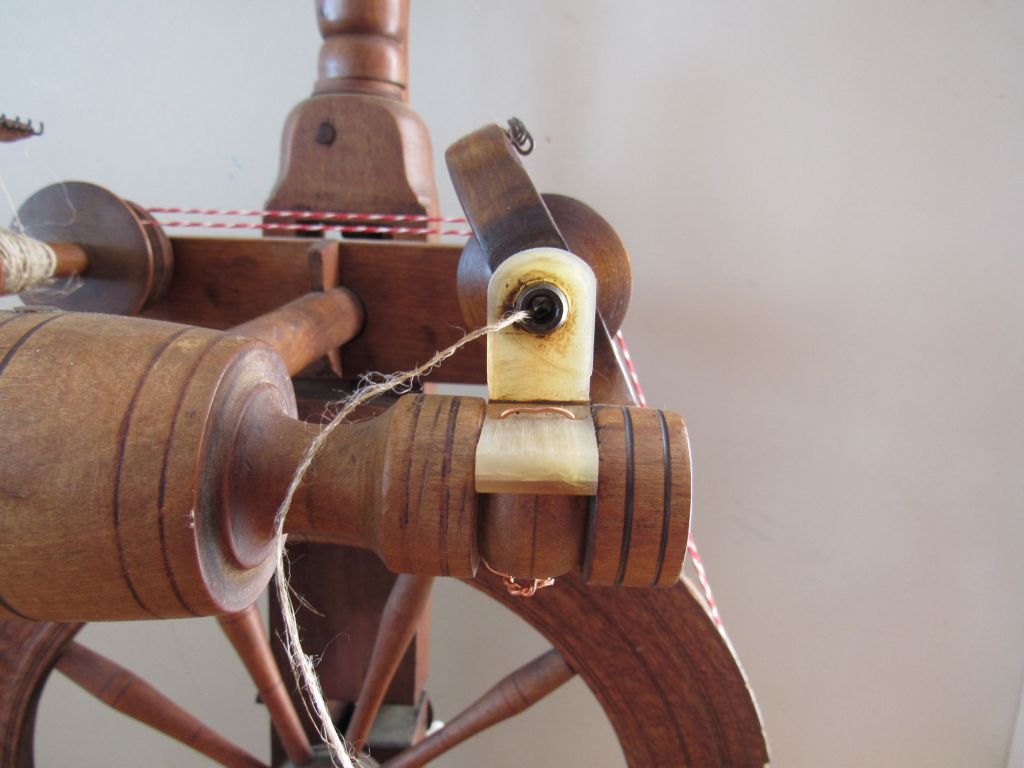

The flyer is beautiful, but was in rough shape when I got it, missing an arm and a good part of the bobbin.

It has some fluting on the orifice and wear marks on the mandrel. After an expert repair, it is back to work.

The axle bearings are thin metal, a bit crumbled,

with unpainted wooden keeper screws for the axle, providing the paint/no paint contrast that I love on so many Scandinavian wheels.

The top of the footman matches the keeper screws–a beautiful feature.

So much thought went into this wheel that I found it strange that the leg by the footman had its ample curve sheared off to make room for the footman. Again, this may be a sign that the treadle is a replacement, and slightly bigger than the original (it does look larger than the treadle on the Minneapolis wheel shown earlier).

The axle was loose in the hub when I bought it, but, with expert direction, I was able to do a shim repair myself. Not something I want to mess with very often.

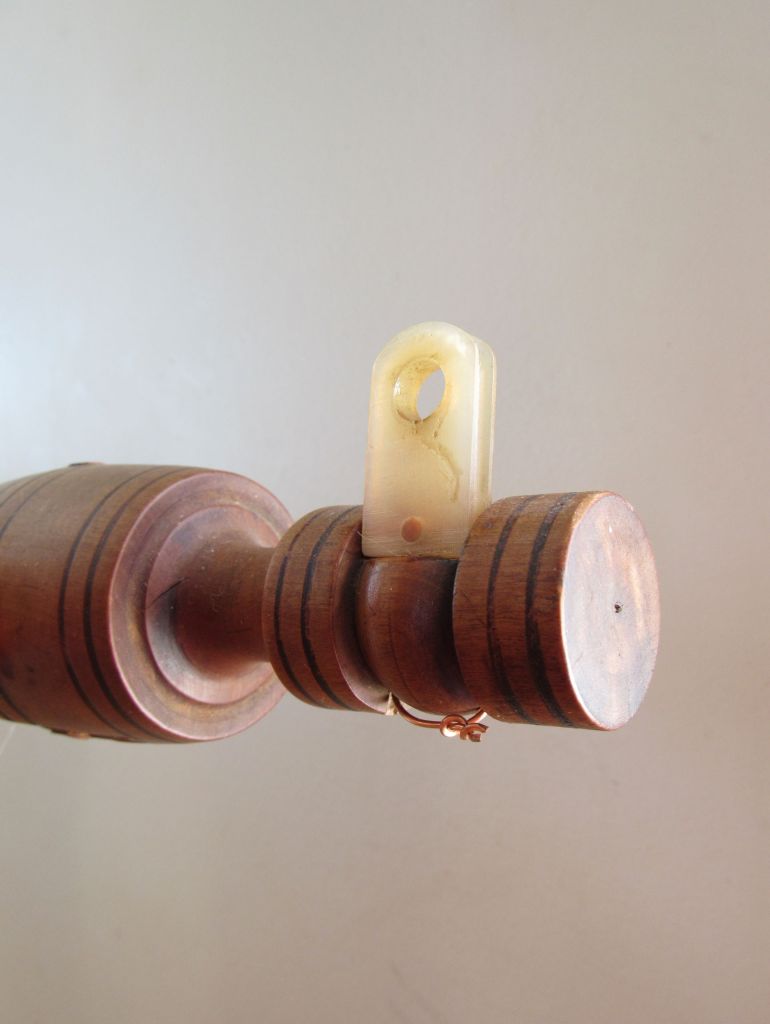

The distaff shaft extends way below with table.

Tuulikki came without the top part of the distaff, so I bought a truncheon style one that is a good match.

I was surprised to find that the top of the distaff unscrews

and the outer portion can be removed from the core.

I do not know if that helps for dressing the distaff or if there is some other reason for this feature. If any one knows, please let me know.

This wheel was created with a real eye toward beauty. But she is a great spinner, too, and has been maintained, with various fixes, as a working machine. I am privileged to be part of the chain of people who have worked on and spun with this special wheel.

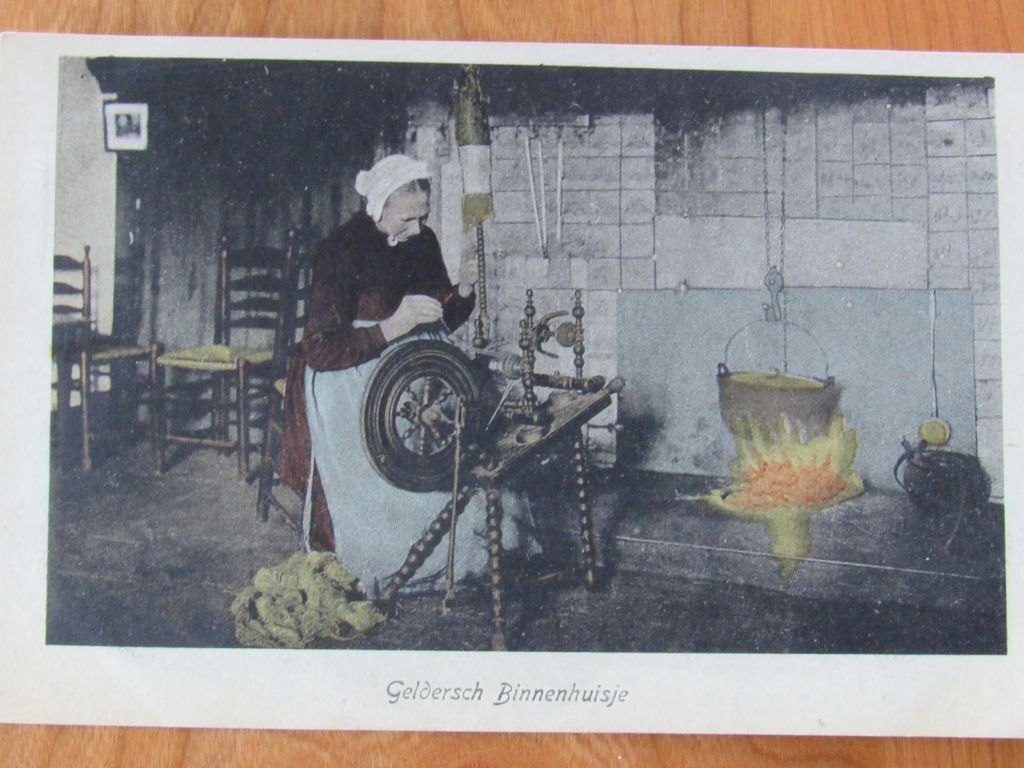

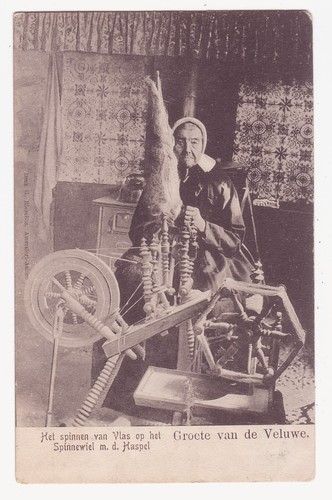

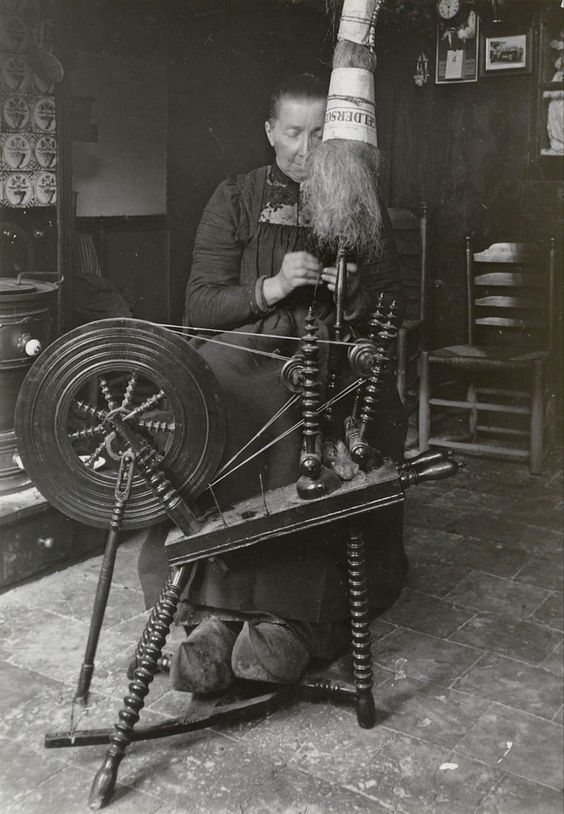

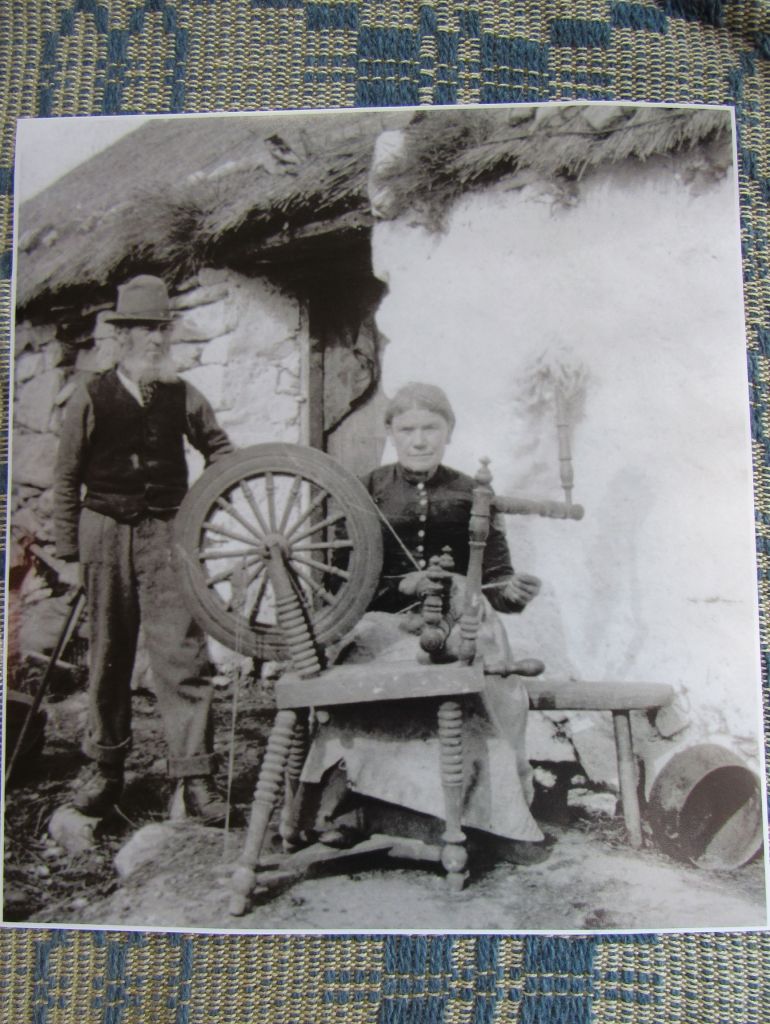

Update June 9, 2025: Thanks to folks on Ravelry, a wheelmaker in Lapua, Finland has been identified who made wheels somewhat similar to this style. Juho Pelanteri (1847-1923) was a third generation wheelmaker who made the wheels in the photo below. These wheels have some features in common with Tuulikki–many fine spokes, generous turnings, wide curvy treadles and often painted–but have different uprights, larger drive wheels, and metal struts. Pelanteri (also referred to as Johan Pelander), with his father and grandfather made about 60 wheels a year–3000 in total. museum link for photos here

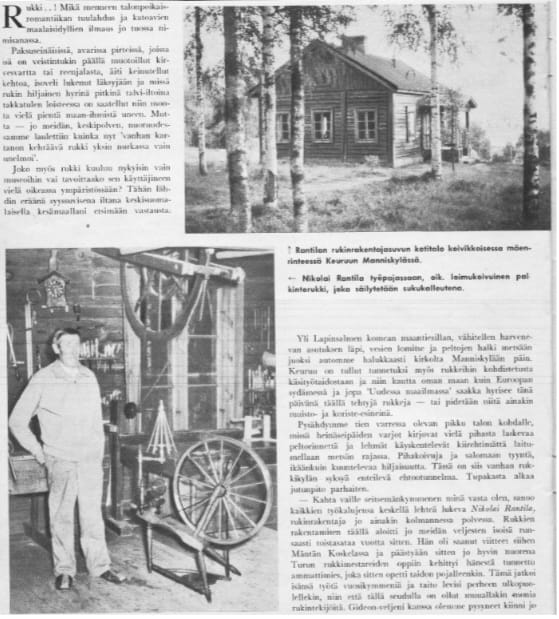

This is the Pelanteri house: