All of the wheels I have documented so far have been from New England—specifically Connecticut and Maine. But many of my favorite wheels are Canadian. I have wheels from Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. They differ hugely in style, but every single one is a splendid spinner.

Probably the most widely known Canadian wheels are from Quebec and now commonly referred to as “Canadian Production Wheels” or CPWs. Caroline Foty, in her book about these wheels, “Fabricant de Rouets,” defines them as double-drive saxony-style wheels with very large drive wheels measuring 27-30 inches in diameter, and having a tension mechanism (usually with metal components), which tilts or slides along the table rather than the more typical wooden screw tension system.

The general time of manufacture was 1875-1935, a period of innovation in wheel design in an attempt to make home spinning more productive and efficient. And CPWs were productive–wonderfully suited to spinning wool fast and fine. But the wheels that fall within the CPW definition are not the only Quebec wheels designed for fast production. Many of the wooden screw tension wheels are extremely fast spinners–some have drive wheel diameters larger than any CPWs, and others have two drive wheels for accelerated speed. So, another way to more precisely categorize Quebec wheels, is: screw-tension, tilt-tension, slide-tension, accelerated, and flat-rim (which sometimes have screw tension and sometimes scotch tension).

Zinnia Rue is a Quebec slide-tension wheel. Her drive wheel is smaller than most CPWs, at just 26 inches.

She appears to have been made by Ferdinand Napoleon Vezina (1841-1898) of Vercheres, Quebec, who likely developed this tension system. Faint remnants of his “F.N. Vezina Vercheres” stamp on the wheel’s table can just barely be discerned.

Ferdinand was part of a family of wheel makers, carpenters, and inventors, including his uncle Joseph, brothers Pierre and Charles, nephew Polycarpe, and son Antoine Emile. Their last name was variously spelled Vezina, Visina, and Vesina (see Fabricants de Rouet, pp. 96-110, for extensive information on the Vezina family).

This beautiful wheel was part of Joan Cummer’s collection. It is wheel No. 87 on page 190 of her book, and in its description, she notes that it is slightly smaller than the usual “Great Canadian” wheels—her term for CPWs. Cummer purchased the wheel from an Antrim, New Hampshire antique dealer and later donated it, along with the rest of her collection to the American Textile History Museum.

It was put up for auction after the museum closed, when I purchased it and brought it home. There were two Cummer Quebec wheels up for auction that night and I was intending to bid on the other one. But when my foot met the treadle on this one, to see if the wheel turned true, I was immediately drawn to it. It is funny how some wheels don’t speak to me at all and others suck me right in. This wheel is a wonderful spinner and I am hoping to pass her on to a friend who has been looking for a CPW and will give her a good home.

She has the common fleur-de-lis style metal treadle and a leather footman

with old greenish (copper?) rivets,

which perhaps was part of a harness originally.

The footman is attached to a to a loop in a wire twisted around the treadle bar.

The front axle bearing has the color and texture of lead,

but the back one is more yellowish.

The flyer was broken and glued and repaired (I since added some metal plates, as back up to the glue) but the arms, interestingly, do not have any wear lines on them and the hooks are in great shape.

The orifice does, however, show wear with some deep grooves where the yarn emerges.

The orifice is bell-shaped and fluted, something seen on many Canadian wheels.

There has been debate about the fluting, with some people arguing that it is a result of wear. On my wheels, the bell shape and fluting go together and appear to be a deliberate manufacturing feature. Wear, as with the deep groove in this wheel’s orifice, looks different to my eyes.

The treadle bars also show lots of wear, indicating that the user probably used both feet to treadle.

There is an added wooden piece on the treadle bar.

I’m not sure if it was intended to elevate the foot or if it had some other purpose.

While the slider and tilt tension wheels did away with the need for wooden tension screws, they retained a sort of residual non-functioning screw that serves as a handle to pick up and carry the wheel.

I love the slider tension on this wheel—just loosen the wing nut and the MOA can be moved in very small increments.

The slider has two parts—one part, bolted to the table, has runner on each end to contain the second part which is bolted to the mother-of-all.

The slider aligns with the spinner side of the wedge-shaped table.

I am a little surprised that this tension style it did not become more popular. Francois Bordua, the creative Quebec wheel maker whose wheels sometimes sported Christmas tree and eagle treadles, also used a slider tension (marked with his initials) on some of his wheels, but slider tensions do not show up very often.

The maidens have a typical Vezina look.

The leather flyer bearings appear to be quite old, perhaps original,

and there is an odd thin nail sticking out of the MOA.

Its purpose is a puzzlement. There also is a nail—what looks like 2 nails, actually, one quite old—in the bottom of the non-spinner side leg, presumably to keep the wheel from sliding across the floor.

The wheel underside has some rough spots.

There is one upright support on the non-spinner side of the wheel.

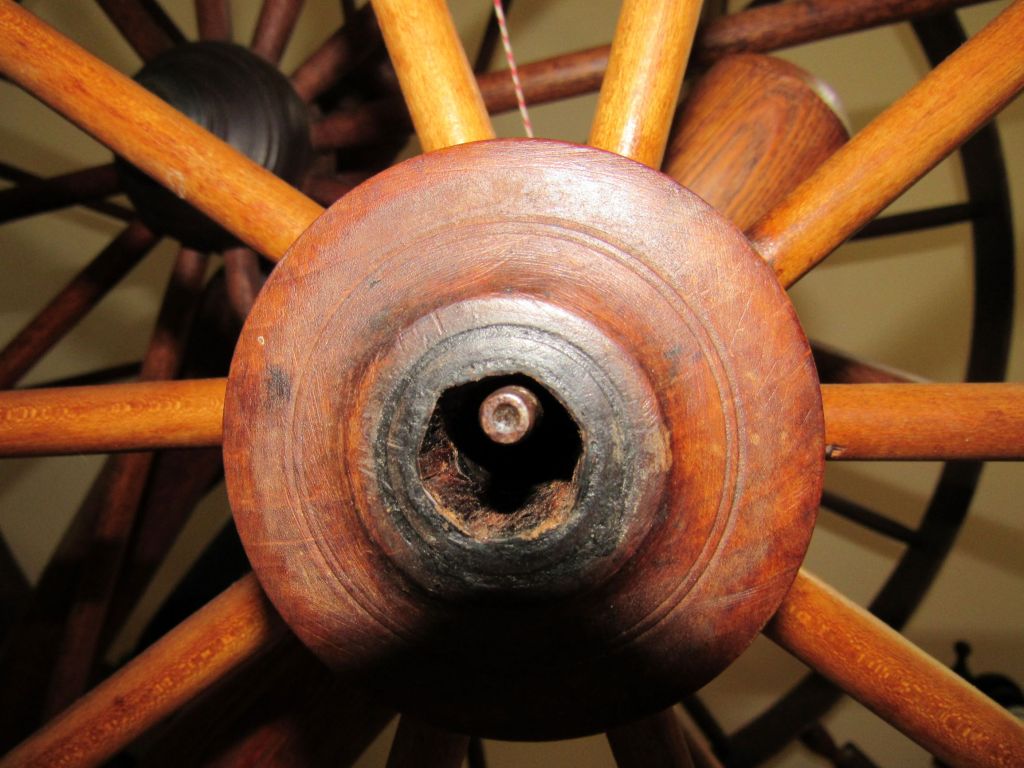

The drive wheel is a bit of a puzzle. Most Vezina wheels have spokes with two or three beads and the earlier ones are even more ornate.

These simple spokes show up occasionally on Quebec wheels of several different makers, but are fairly unusual.

Oddly, both of my Vezina wheels have this spoke style. The drive wheel rim also is not typical of Vezina wheels, which tend to have a simple three mound “quilted” rim. This one is more interesting.

While drive wheels and other parts were often mixed and matched as needed, this particular drive wheel is not associated with any particular maker, as far as I know. The drive wheel is multi-colored, with most of the wood being dark, but some being light. The rest of the wheel also has different shades of wood. And the drive wheel look as if it belongs.

So, I am inclined to think it is original, but it is hard to say. Original or not, it carries a mark of the maker, whoever he may be. There is a saw mark on the rim where it looks as if a cut was started at the wrong angle but then used with mistake intact.

Another feature of this wheel is the wood itself.

Quebec production wheels were turned out at a great rate with a good price.

Beauty in wood was not a prime consideration. Yet, this wheel’s wood is worth a slow look and appreciation.

For more information on Canadian wheels see:

Burnham, Harold B. and Dorothy K., ‘Keep Me Warm One Night’ Early Handweaving in eastern Canada, Univ. of Toronto Press, Toronto and Buffalo, 1972.

Buxton-Keenlyside, Judith, Selected Canadian Spinning Wheels in Perspective: An Analytical Approach, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa, 1990

Cummer, Joan, A Book of Spinning Wheels, Peter E. Randall, Portsmouth, N.H. 1984

Foty, Caroline, Fabricants de Rouets— this book is available for sale as a downloadable PDF by contacting “Fiddletwist” by message on Ravelry.