The Maine Shakers made thousands of spinning wheels and I am lucky enough to have one.

Shaker missionaries first started settling in Maine in the 1780s and by the early 1790s had established several formal communities. Two of those communities, Sabbathday Lake and Alfred, starting producing wheels soon after.

Many Shaker communities in other states also were involved in wheel production and it’s estimated that the communities combined may have produced more than 10,000 spinning wheels from the 1790s to the mid-1800s. My wheel was made in Alfred, Maine.

Maine’s Alfred community was a major wheel producer, perhaps turning out as many as 3000, the majority being wool wheels.

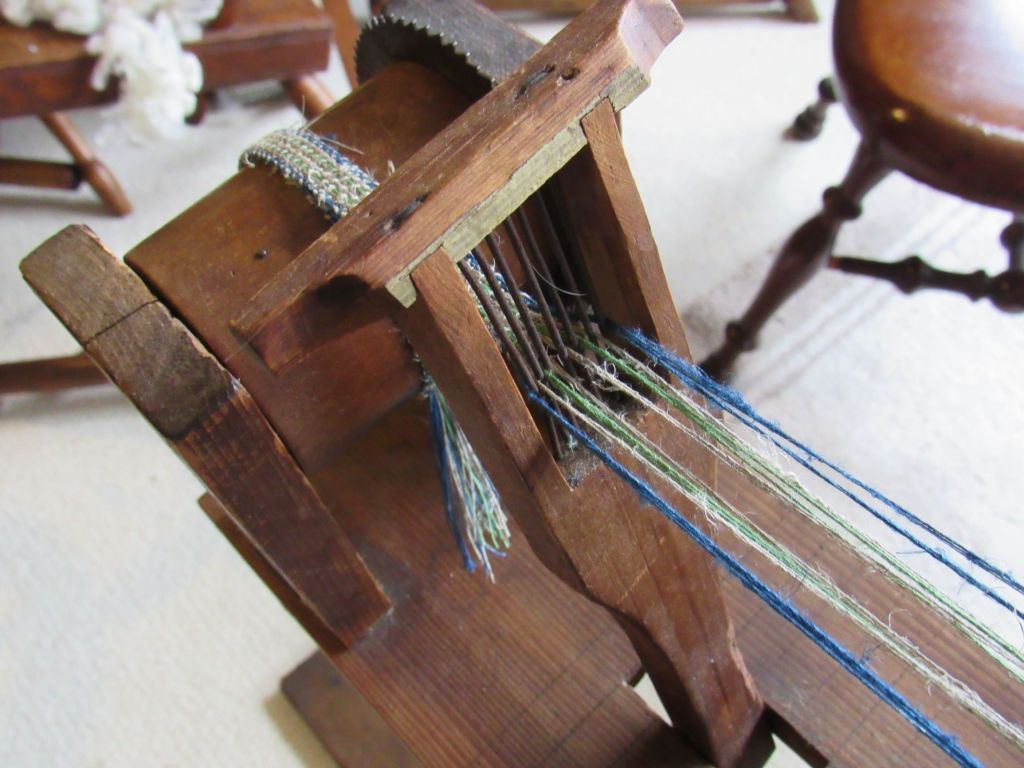

But they did produce flax wheels, too, with simple, graceful lines highlighting wood that appears to have been carefully chosen for its beautiful grain patterns and ray flecks.

The Shakers didn’t mark all of their wheels, but many have initials stamped in the end grain of the tables. The initials were those of the community’s trustees, who may or may not also have been wheel makers. The earliest Alfred wheels were marked “TC” for trustee Thomas Cushman and, after 1809, flax wheels were marked “SR AL” for trustee Samuel Ring.

Even though Ring wasn’t a trustee for long and wasn’t a wheel maker, his name continued on the wheels after he retired in 1814. Those initials must have essentially become a brand for Alfred Lake wheels at that point.

The simple design of Shaker wheels was a huge influence on other wheel makers in Maine and New Hampshire. The designs were similar between the different Shaker communities, but each community’s wheels had some distinctive features. The Alfred Lake wheels have beautifully curved maidens with small teardrops at the top.

The wheel upright supports are encircled with multiple scribe marks.

Mine has four on each side.

Whether the number of marks has any significance is up for debate. There are fourteen plain spokes–with no ornamentation.

The treadle bar usually is a half-moon shape, likely designed for ease in using both feet to treadle.

The legs have a gentle curve with a rounded foot. I’m always struck by how many of the shapes on these flax wheels resemble curves in the human body–an interesting feature since the Shakers were celibate.

The flyer assembly and distaff top are not original to my wheel, although both are probably from other Shaker wheels. Mine is an absolutely wonderful spinner, especially for flax. And she’s easy on the eyes.

My resources for the information on Shaker wheels are:

Pennington, David A. and Michael B. Taylor. Spinning Wheels and Accessories. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2004, pp. 131-39.

Michael Taylor, “Shaker Spinning Wheel Study Expands,” The Shaker Messenger, Vol. 8, No. 2, (spring 1986).