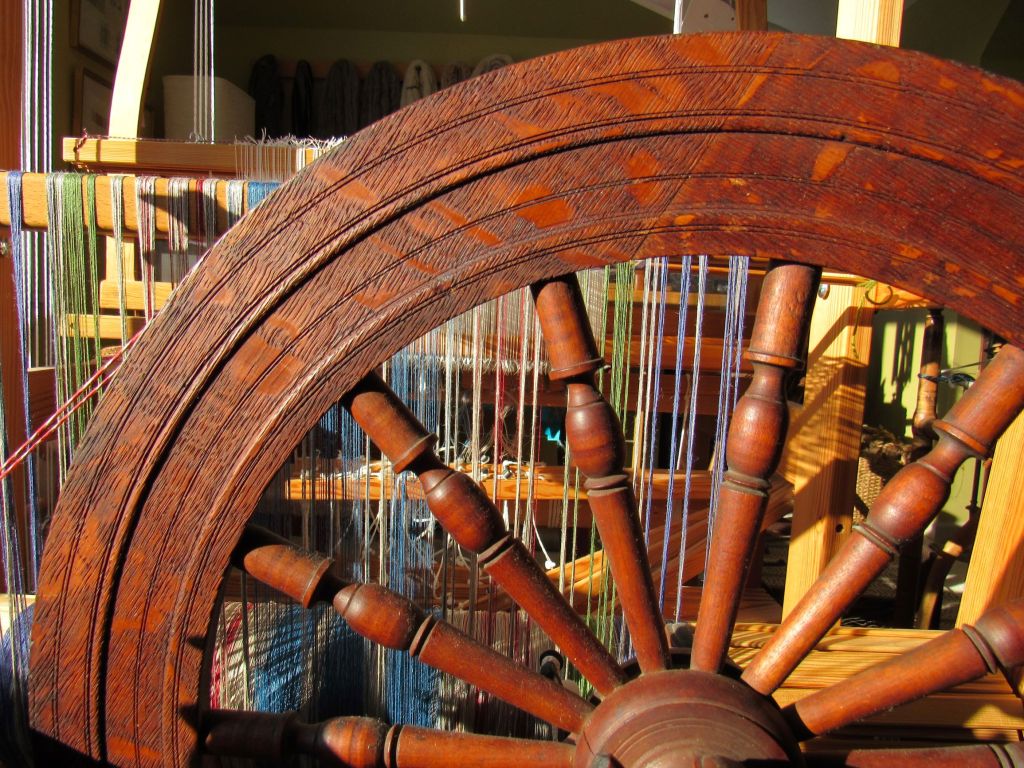

This wheel—made more than two hundred years ago—is a testament to the superb skills of Connecticut wheel makers in the late 18th and early 19th century. It was made by Silas Barnum (1775-1828), one of a group of wheel makers from southwest Connecticut, who are most well-known today for their double flyer wheels.

From this group, the most well-known are Solomon Plant, the Sanfords, the Sturdevants, and Silas Barnum. The earliest, born in the 1740s, included Solomon Plant and Samuel Sanford, two men who likely were making wheels before the Revolution. A second generation, born in the 1760s and 70s, arose with John Sturdevant, Jr., Isaac Sanford (Samuel’s son), and Silas Barnum, who, in turn, were followed by another generation, born in the 1790’s, including Beardsley Sanford (Samuel’s great-nephew), Elias Bristol Sanford (Isaac’s son), Josiah Sanford (Samuel’s son by his second wife), and John Sanford Sturdevant (John Sturdevant Jr.’s son).

J. Platt appears to have been part of this group, too, but, as far as I know, no one has determined just who he was. These men, and a few others, made wheels of a distinctive style, recognizable immediately as having come from a particular time and place in our history.

For more on these wheel makers, see the previous posts: “Mindful Pond” (Solomon Plant); “Louisa Lenore” (Sanfords); and “Katherine the Witch,” “Mercy,” and “Judith and Prudence” (J. Platt).

To help keep these wheel makers sorted out, in a previous post about Silas Barnum, “Big Bear,” I included a timeline, map, and family history that helps to understand how these particular wheel makers were connected. All of them were from families that settled on the Connecticut shore in the 17th century and gradually migrated inland.

Their family names are found repeatedly, along with Platts, Pecks, Smiths, Beardsleys, and others, in the history of this area. Silas’s mother was a Sturdevant, his older sister, Sarah, married wheel maker, John Sturdevant, Jr. Their son (Silas’s nephew), John Sanford Sturdevant (likely named after his Sanford grandmother) was also a wheel maker. Silas married Martha Platt, although whether she was related to wheelmaker J. Platt remains a mystery.

While there is ample evidence of family relationships between Barnum and other Connecticut wheel makers, we know little about their working relationships. Did Barnum work with his brother-in-law, Sturdevant, Platt, or any others? How well did these men know each other? Was their wheel making competitive or cooperative, or a likely mix of the two? We just do not know.

We know that Barnum, the Sanfords, the Sturdevants, and likely Platt, worked in neighboring towns and their wheels share some remarkable similarities, so there was cross-pollination, but it would be fascinating to know more about the interplay of design influences, creativity, innovation, and marketing.

For example, in trying to determine how J. Platt fit into this group, I was struck by the remarkable similarities between Platt and Barnum’s great wheels (see “Big Bear”), which seemed to indicate some relationship between the two men. But, when I found Barnum’s flax wheel, I was surprised by how different it was to Platt’s in the details.

Was the difference one reflecting the time they were made or just the personal style of the makers?

Barnum’s wheel is more finely and elaborately turned and has the small chip carvings dotted on decorative black bands so typical of these Connecticut wheels (but missing from Platt’s).

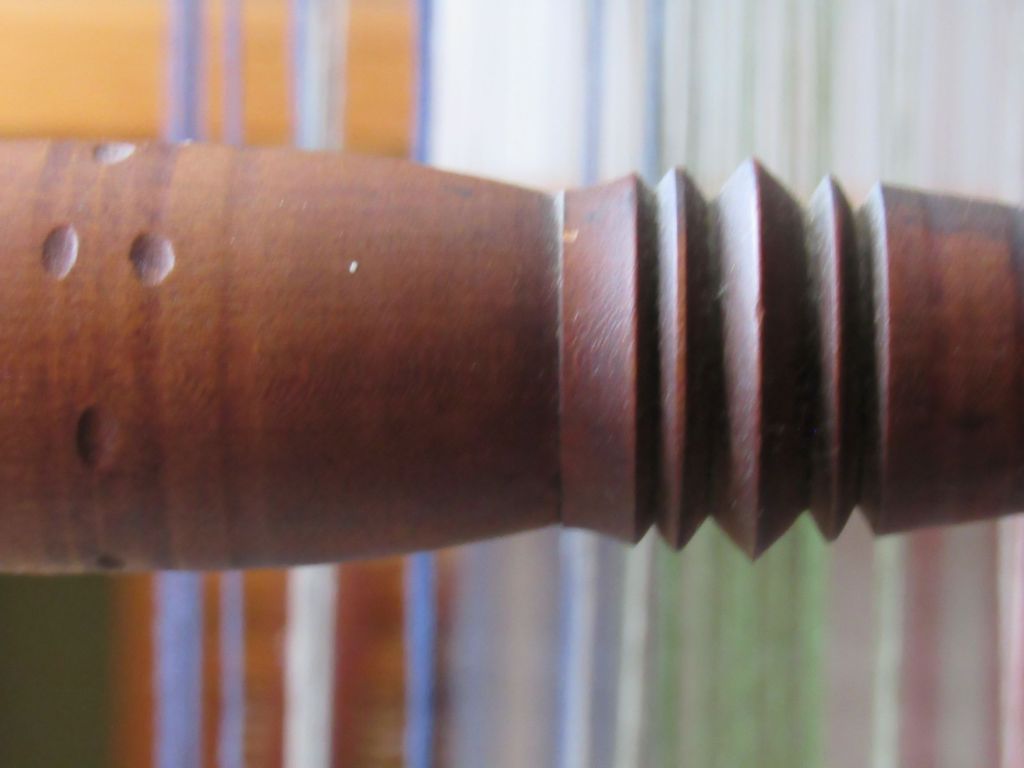

The spokes, also, are different.

Barnum’s spokes are more elaborate. He used the wonderfully-named “shotgun shell and olive” style, often found on Connecticut and Pennsylvania wheels of this era.

Despite these differences, though, both wheels share the same overall look and excellent craftsmanship typical of this group of wheel makers.

Barnum’s fine work on this wheel is illustrated by the spokes.

They rest up against the rim lip, with pegs cut perfectly flush with the drive rim.

Despite the wheel’s impressive age, not a spoke has a wiggle or gap, and the drive wheel is perfectly solid, straight and aligned. The drive rim’s four parts have different patterns of shining ray flecks that glow in the sun.

There are fine turnings on the maidens and distaff (the top part is missing).

In contrast, the table is a bit more crude,

appearing to have been cut from an imperfect chunk of lumber, with one bottom edge at an angle and a concave area on the top.

Perhaps Barnum chose it for the grain, which, as with the drive rim, has highly contrasting fleck.

The table underside is smooth, without scribe marks.

The wheel end legs stick up through the table.

Each leg as a nail in the bottom, which is fairly unusual, in my experience.

I often find one in the far-side leg, but seldom in all legs.

The wheel shows considerable use,

but is in excellent working condition.

The treadle is almost worn through at the front

and right side edge and bar.

The original flyer assembly is missing. It came with a funky one that likely was made in the 1970s or so. I replaced it with one that fits perfectly and has its own elegant style, well-suited to the wheel.

The spinner-side maiden is pegged into the mother-of-all

but the far-side one only has small peg underneath,

which keeps it in the mother-of-all but allows it to turn for easy flyer removal of the flyer.

The tension knob shows no signs of wear from being used for winding off.

There is one unturned secondary upright support that runs to the table.

This is a common feature seen on these Connecticut wheels. There are chip carvings on both ends of the table

and deep double grooves down each side.

It came with a rawhide footman attached to the treadle bar with a metal hook with a nut underneath.

As I mentioned earlier, Barnum’s life spanned the period at the end of the first generation and beginning of the next generation of these Connecticut wheel makers.

To some extent, this must have been a transition period. His spokes and turnings are similar to Solomon Plant’s, but a little more refined.

The olive and shotgun shell spoke was found on the early Sanford wheels and those of John Sturdevant Jr. and Solomon Plant. But, the later Sanford wheels evolved to have simpler spokes and finials, which according to Pennington & Taylor’s book “Spinning Wheels and Accessories,” this evolution reflected the change in style to plainer turnings for furniture in the 1810s to 1830s (p. 81).

Barnum did, interestingly, venture into a style of double flyer wheel that the later generation of Sanfords embraced, with the wheel above the flyers rather than below.

In discussing this style wheel, Pennington & Taylor highlight one made by Elias Bristol (E.B.) Sanford, who was born 16 years after Barnum (p. 82-83). E. B. Sanford apparently patented the wheel in 1816. It had unusual metal flyers, but the tension system looks very similar to a wheel signed by Barnum, which was discovered languishing in a North Carolina junk shop by Kelley Dew a few years ago.

Kelley generously shared photos of her wheel,

showing similarities to E.B. Sanford’s, even down to the unusual decorative black marks on the wheel post.

There are differences in the wheels,

but enough similarities to indicate that one maker influenced the other.

Elias Bristol would have been about twenty-five years old when his patent was granted, while Barnum would have been forty-one.

Did the older Barnum first make his wheel and then Elias Bristol improved and patented it?

Or did Barnum take from Elias Bristol’s design, possibly without the patented parts? Who knows?

Fascinating to think about, though.

I am still hoping to learn more about Silas Barnum.

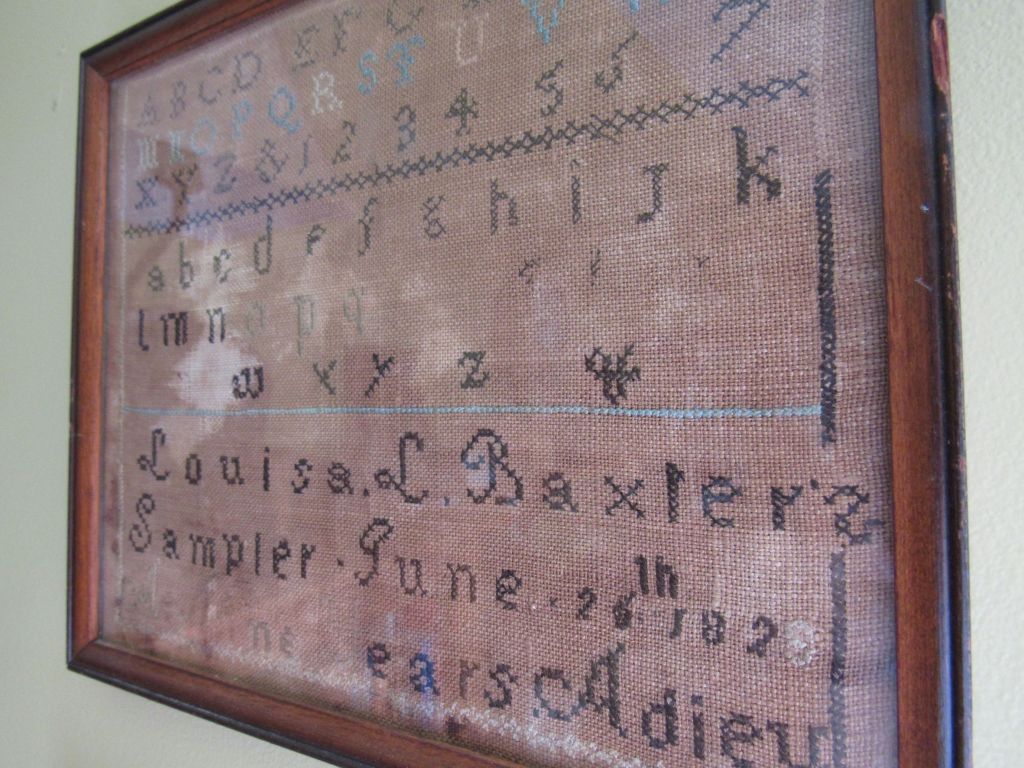

I knew that I had Barnums in my Connecticut family background and recently learned that my great, great, great, great grandmother, Hannah Barnum Baxter, was Silas Barnum’s older cousin.

She married and moved to upstate New York before Silas was born, so likely never knew him. But spinning on a wheel made by someone sharing a small part of my ancestry gives me a special thrill of connection.

Thank you to Kelley Dew for allowing me to share her photographs of her stunning Barnum double flyer wheel.

For more information

Bacheller, Sue and Feldman-Wood, Florence, “S. Barnum and J. Sturdevant Double Flyer Wheels,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue #31, January 2001 (and “Update” Issue #32, April 2001).

Pennington, David A. and Michael B. Taylor. Spinning Wheels and Accessories. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2004, pp. 81-83.