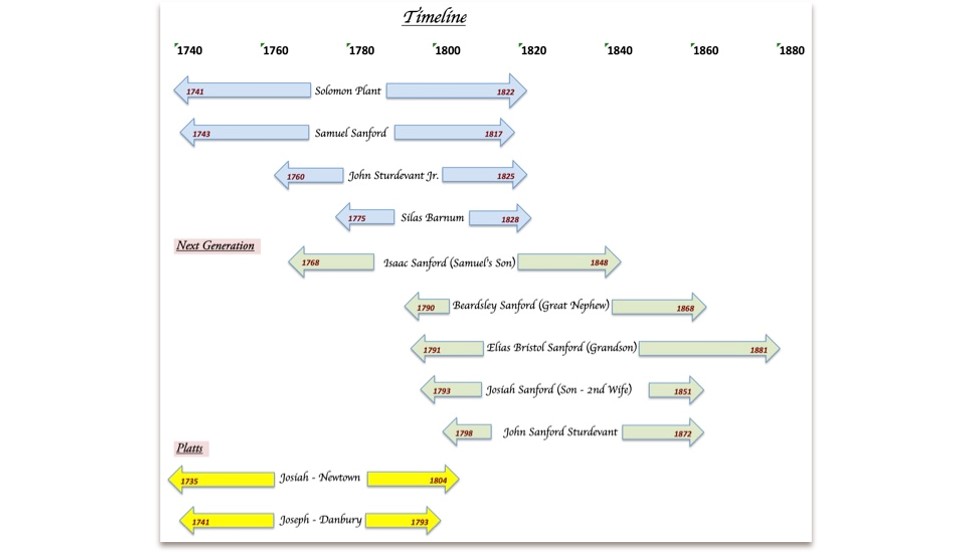

Silas Barnum (1775-1825) was part of a group of Connecticut wheel makers working in the late-1700s to mid-1800s. They spanned generations and had numerous connections–some clear, others more elusive. I like to refer to the early generation–Barnum, Samuel Sanford, John Sturdevant, Jr., Solomon Plant, and J. Platt–as the “double flyer boys,” because they are best known today for their distinctive upright double flyer wheels.

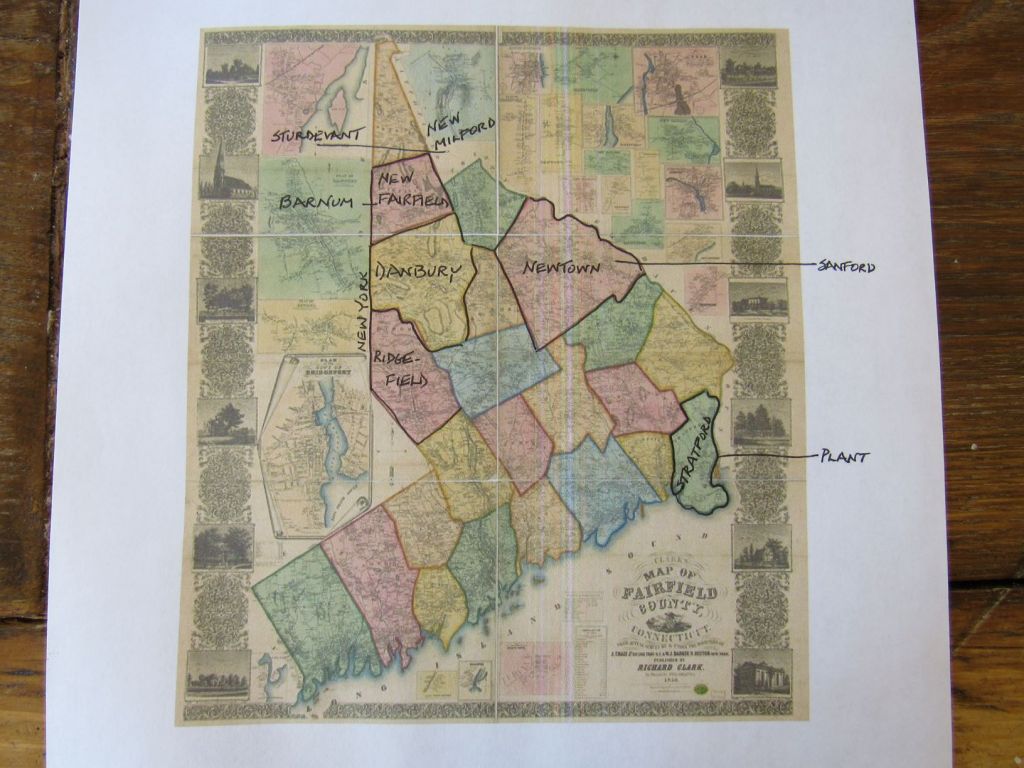

These men and their wheels share many similarities. With the exception of Plant, who lived a few towns away on the coast, they lived in neighboring towns in southwest Connecticut.

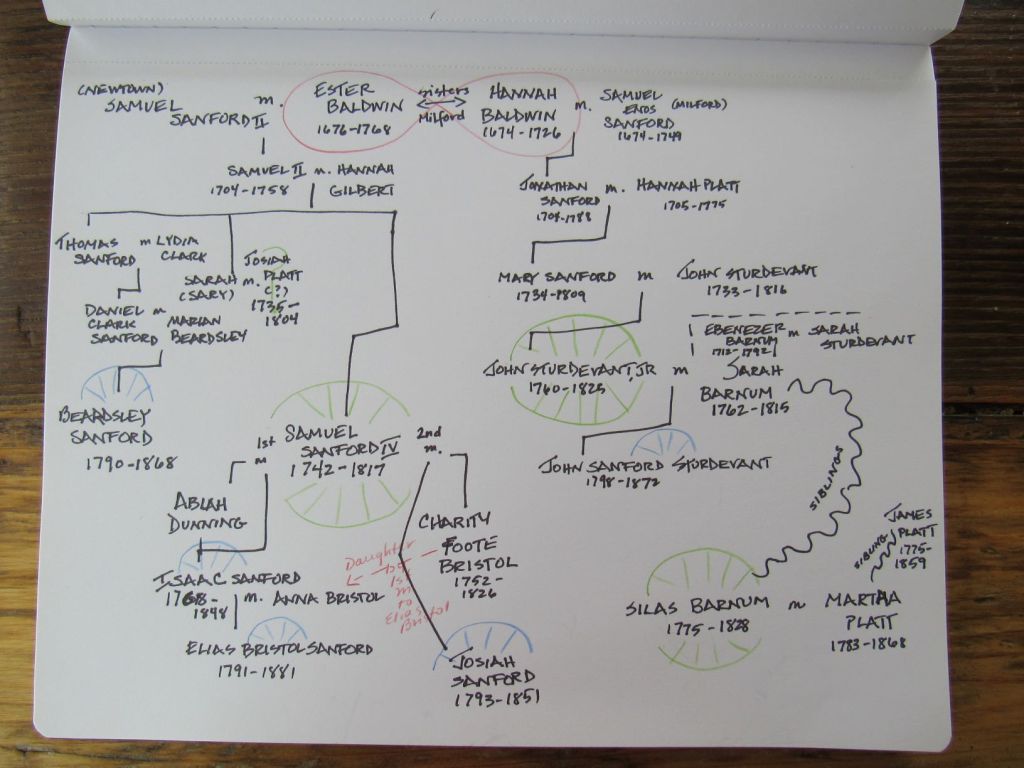

Their families were early settlers in the area, with a web of interconnected family relationships. For example, Silas Barnum’s older sister, Sarah, was married to wheel maker John Sturdevant, Jr.

This chart is the best I’ve been able to do in tracking the family connections.

We don’t know whether some of these men apprenticed or worked for others or if the similarity in their wheels simply reflected what was in demand at the time.

It’s doubtful that the similarities were just market driven, however, since Silas Cheney—who was working in the same time period just a couple of towns away—made wheels in an entirely different style (see previous post—”Sweet Cicely and Chancey”). And, with all of the family ties, there must have been shared work and design tendencies to leave such a legacy of style.

I found my Silas Barnum great wheel, “Big Bear,” on Facebook.

The seller, a spinner in New Haven, Connecticut, had recently bought it at an estate sale of her artist neighbor—a very old man at the time of his death.

She believed that he had owned the wheel for many decades. It’s a big, solid wheel, with a two-posted barrel tension system and lovely direct drive head. It’s hard to tell if the head is original to the wheel, since they were so often replaced or interchanged.

The style is right—many of Barnum’s wheel predated accelerated heads and these nicely turned spindle supports were typical of the time and region.

The wood is lighter than the wheel itself and, interestingly, has the dark bands so prevalent on the flax wheels of this group of wheel makers.

The wheel has a large crack in the table that was nicely repaired with pegs.

The drive wheel rim is beautiful ray-flecked oak, with a generous 3 inch width, and a 41 ½ inch diameter.

It’s a good spinner, with a wheel that invites the body to lean in and work with its heft, weighted so that the wheel comes to rest at a certain point.

There is a remarkable similarity to J. Platt’s great wheel (“Mercy” in previous post), although the Platt drive wheel has a larger 44” diameter and the rim is a smaller 2 5/8 inch width.

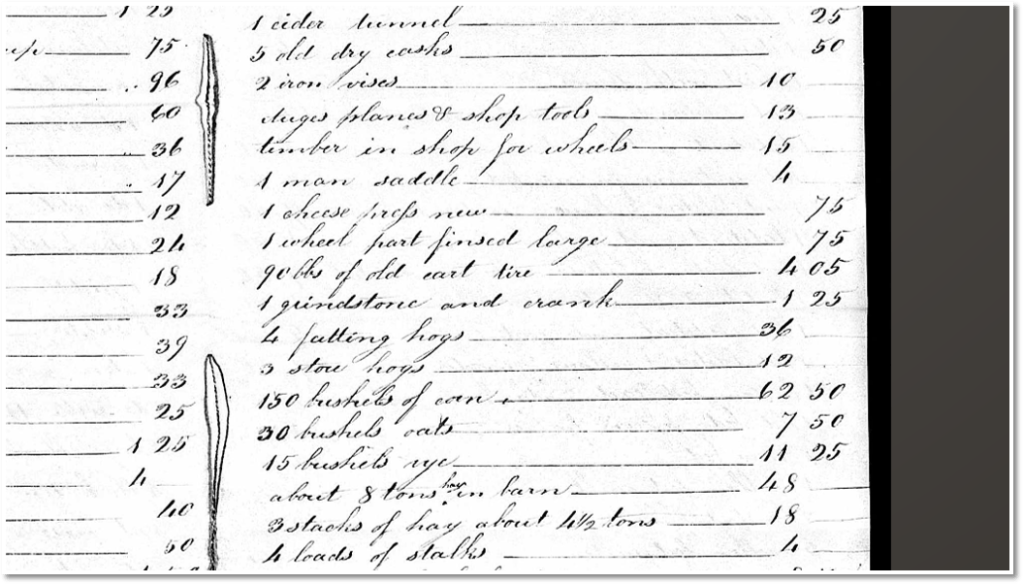

I did a lot of research into possible connections between Barnum and Platt—digging into family trees and probate records. As with most wheel makers, probate inventories reveal a lot (and give a fascinating glimpse into 19th century life).

Barnum’s shows clearly that he was a wheel maker, referring to “timber in shop for wheels,” and “1 wheel part finished large.” In my research, I found several J. Platt connections with Silas Barnum. But none of their probate records showed a wheel maker. The first was through Barnum’s wife, Martha Platt. I had high hopes that her brother James might be J. Platt the wheel maker, but probate records showed that he was a city dweller and no craftsman.

A Josiah Platt was another good possibility. He married Sary Sanford, sister to wheel maker Samuel Sanford, but there is no evidence at all that he was a wheel maker or had anything to do with furniture making and the timing isn’t quite right. There is a Joseph Platt that could possibly be our man—he had some connections with Barnum and appears to have done some furniture making—but the evidence is inconclusive.

So, I’m still researching the Barnum/Platt connection. Whatever the maker’s relationship, the wheels look like siblings—closely related, but with their own unique characteristics. More information can be found on Silas Barnum and his double flyer wheels in the Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issues 31 and 32.