If the value of a wheel can be measured by the lengths taken to keep it spinning, this wheel must have been very highly regarded. It could be a textbook for how to keep a spinning wheel running with whatever is on hand. Belying modern wheel owners who too often declare such wheels “a piece of junk,” and those who insist that flyer arms must be “balanced,” with all its makeshift repairs, this wheel still spins beautifully, more than two hundred years after it was made.

The wheel was part of Joan Cummer’s collection, which she donated to the now-defunct American Textile History Museum. Along with most of Cummer’s wheels, it was auctioned off after the museum closed and I was fortunate enough to become the next owner.

The wheel, “No. 34,” is pictured and described on pages 80-81 in Cummer’s “A Book of Spinning Wheels.” Cummer notes that it “is probably Scandinavian judging by the slope of the table and general proportions.” (p. 80) She did not know that the wheel contained a hidden clue as to its origin.

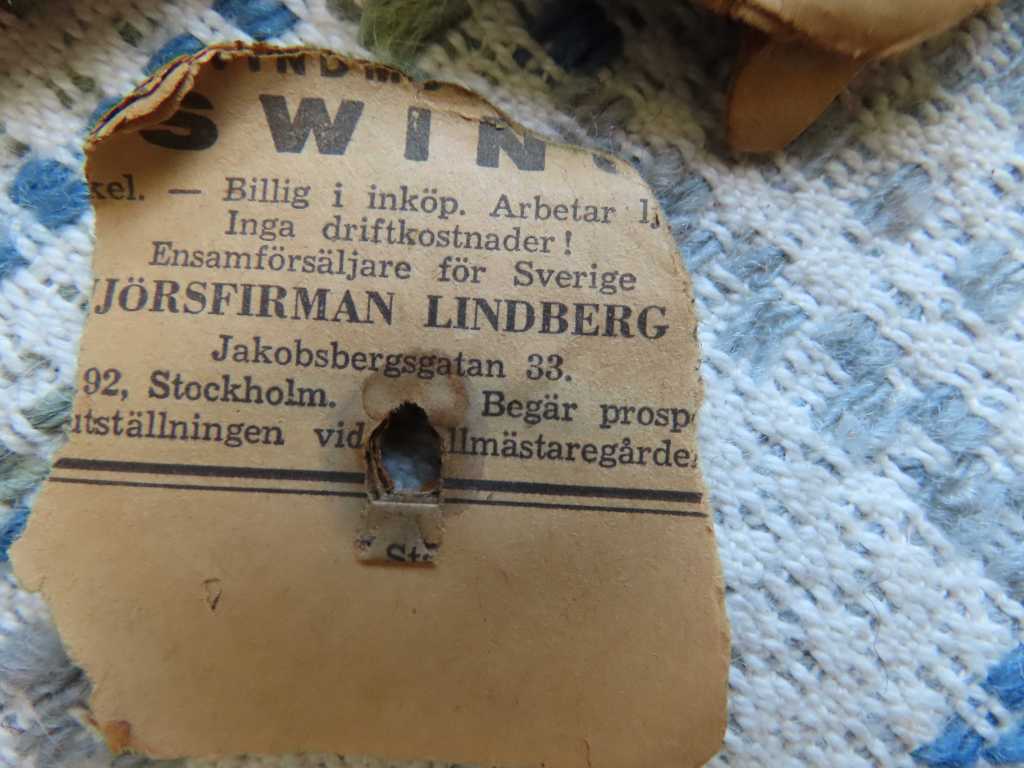

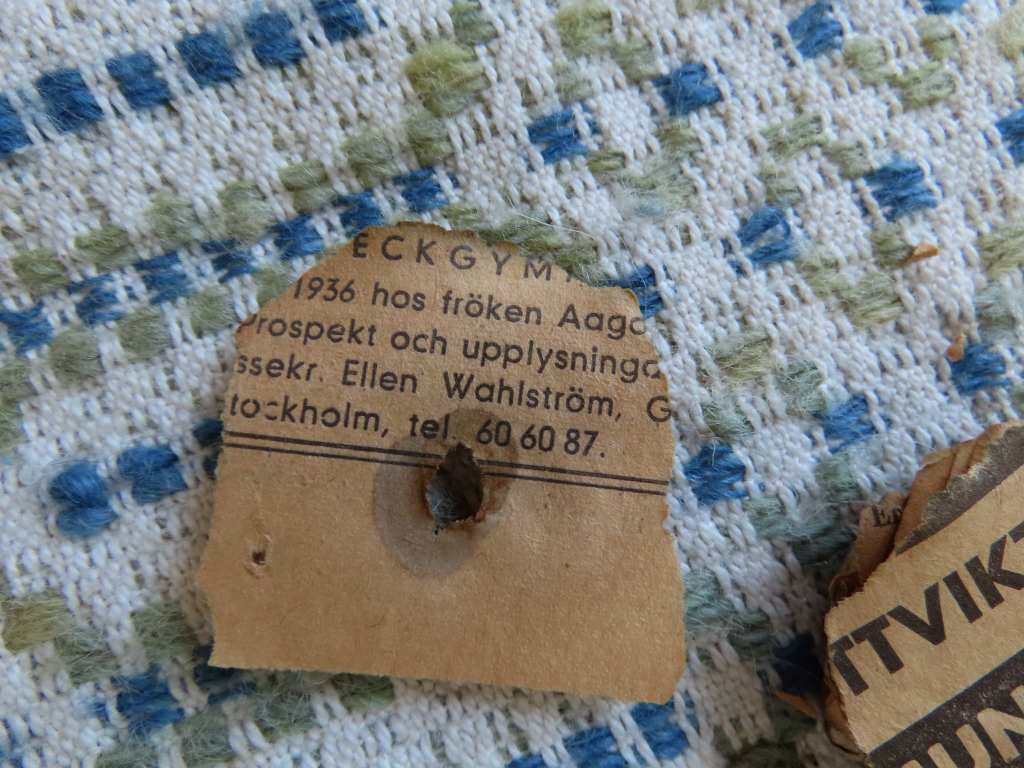

After bringing the wheel home, I wanted to get it spinning. On the mandrel, between the bobbin and flyer arms, was a spacer made from layers of leather, cardboard, and newspaper.

I carefully removed the layers and found that the newspaper pieces were in Swedish and contained Stockholm addresses and the date 1936,

evidence that this wheel—made in 1818—was being used well into the 1930s, either in Sweden, or by Swedish immigrants with access to a Swedish newspaper.

That was all I knew about this wheel until the fall of 2023, when the Rydals Museum in Sweden advertised on their Facebook page a presentation by Hans Johansson on wheels made in Hyssna, Sweden. Johansson runs Kvarnen y Hyssna (The Mill at Hyssna) (this link to his website has fantastic old photographs of Hyssna). Johansson is the fourth generation of a mill and sawmill family in Hyssna, a town east of Gothenburg, Sweden. With its ample water power and lumber, the town had a tradition of woodturning, passed down from father to son since the 16th century. By the mid-19th century, there were about fifty spinning wheel makers in the area, making a distinctive wheel style associated with Hyssna.

These “Hyssnarocken” were pictured on the Rydal Museum’s notice of Johansson’s talk and I excitedly realized that my 1818 wheel, Astrid, shared their features.

Although the museum people confirmed that Astrid likely is a Hyssna wheel, I have not been able to identify the actual maker. The most well-known Hyssna wheelmakers seem to be fairly recent ones–Johannes Persson and his son, Oscar (who was making wheels into the 1970s). The 1818 date on Astrid is the earliest I have seen on a Hyssna wheel.

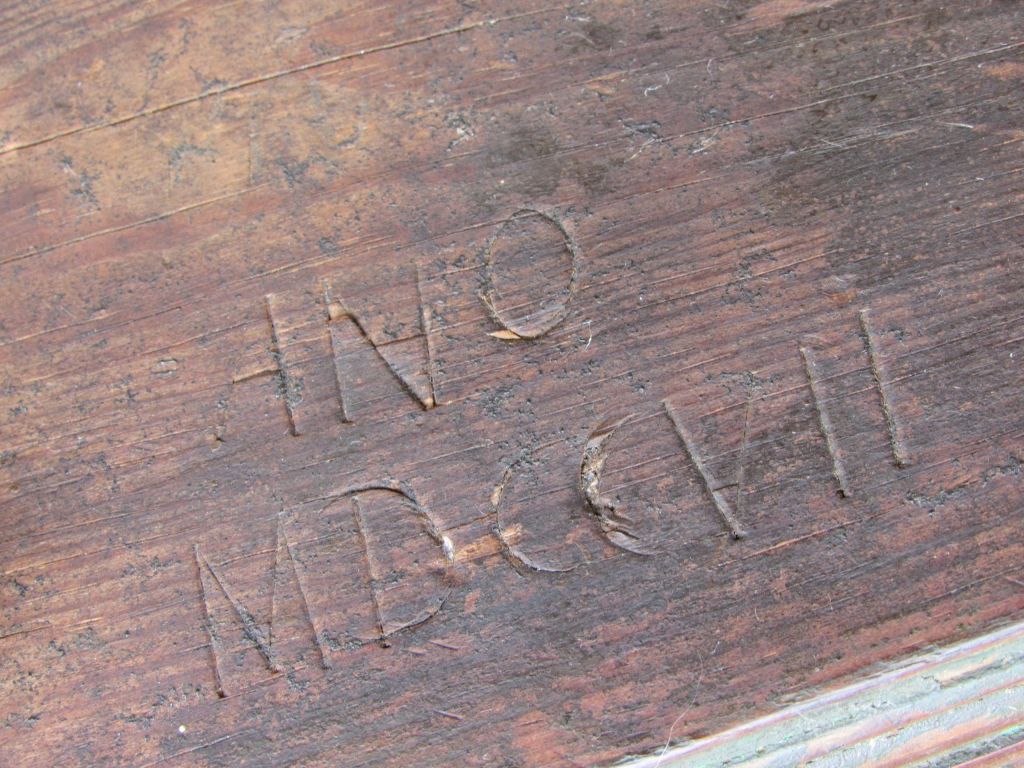

With that date and the initials “ACSS” on the table end and “BAS” on the table top, it probably would not be too hard to trace the maker. But, with my limited Swedish skills, I am happy at this point just to know where the wheel is from.

Hyssna wheels have several distinctive features. There is a particular tilt to the table and angle of the legs that mark them, even from a distance.

They have painted highlights, usually in red, green, and black.

Aside from the painting, the wood has an unfinished, almost rough quality.

The table has initials, and often a date, carved and painted on its top, accompanied by decorative carving.

As Joan Cummer mentioned in her book, it is generally believed that initials on the end of the table belong to the maker, while those on the top are those of the owner. Whether that is always the case with Hyssna wheels, I do know, but the wheel in this Clara Falk blog post appears to have Johannes Persson’s initials on the table, if I understand correctly.

Two secondary upright supports extend down to the legs and the axles are held in place with pegs that go down the side of the upright rather than across it.

Another unique feature for most Hyssna wheels is the treadle set up, in which the treadling is done by the foot (or feet) resting across the cross bars rather than on a flat treadle piece. There is a small piece between the cross bars to the right of the spinner’s feet and the spinner-side legs go through the cross bar.

Astrid has a more traditional treadle set up, which leads to the fascinating fixes made to this wheel over the years.

There are holes in the legs for treadle bar pins, which usually would not have been present in Hyssna wheels. Oddly, in this case, in addition to the holes, someone fashioned a metal bracket to hold a pin rather than have it go through the leg.

It is possible that the treadle set up is a replacement—its turnings and wood look a bit different than the rest of the wheel—and it may not have fit the holes well. Or perhaps it is original and just popped out of the hole too much. A similar metal bracket holds the axle in place after the hole for the axle peg eroded and was no longer functional

and a front axle bearing was made with folded metal hammered into the upright.

While it is hard to tell if the treadle set-up is a replacement, it is easy to see that the spinner-side maiden came from another wheel.

Not only does it have mismatched turnings, it does not come close to fitting properly in its hole. The peg to hold it in place is missing but someone stuffed a piece of fabric under the maiden which holds it tight and lends a nice bit of history to the wheel.

The collar for the mother-of-all is shimmed with layers of paper and leather.

The wheel rim, still bearing paint traces, has a largish gap showing a peg at an awkward angle.

The crowning glory of the make-do repairs is the flyer, with its now-rusty metal patch holding a broken flyer arm in place. I replaced the spacer made of leather and newspaper with some woolen yarn wrapped on the mandrel. The whole thing looks a mess and certainly is not balanced, but it spins surprisingly well.

The orifice only has a one-sided opening as it emerges to the flyer.

The table underside is beautifully shaped

but my favorite touch is the decorative shaping of the wheel end of the table.

Joan Cummer noted that the other “end of the table bearing the tensioning screw is beautifully shaped and sculptured. Much care and pride seems to have been taken in the making of this wheel.” (p. 80) I agree. And much care was taken to keep it functioning for over 200 years.

Thank you to the Rydals Museum staff for their patience and time in helping me learn about the Hyssna wheels.

The information on Hyssna wheels is from the Rydal Museum’s summary of Hans Johansson’s presentation and a piece that he wrote: “Spinnrockar, förläggare och svavtradition i Hyssna,” which is in a book available through the museum.