I know little about this wheel. A vertical double flyer wheel, stamped on two sides with a “D.S” maker’s mark, seems distinctive enough to have generated some body of research.

But this style seems to be a bit of a mystery.

The most familiar North American double flyer wheels are the two-table variety made in Connecticut in the early 19th century (see the post “Louisa Lenore”).

According to Pennington & Taylor, who refer to this lesser-known style as “t-top” double flyers, they likely were made during the the same popular surge of Connecticut double flyer wheels that produced the two-table version. (Spinning Wheels and Accessories, p. 86-87)

I do not know what evidence indicates that the t-tops were also made in Connecticut, but it would be interesting to know if they were a double-flyer variation that evolved in a different geographic area of the state or in a nearby state.

Why double-flyer wheels became so popular in Connecticut at that time is not really clear, but I find it interesting that both of the Connecticut double flyer wheels I have owned appear to have been little used.

It makes me wonder if the wheels became a “must have” item but, once acquired, spinners realized that they preferred their single flyers.

After all, while double flyer spinning increases production, it takes a skilled spinner and fine flax to produce as consistent high quality linen thread as on a single flyer wheel (see the update to “Louisa Lenore” for more information on double-flyer spinning production).

I am not aware of any evidence suggesting that these double flyer wheels were used for a specific purpose in Connecticut, such as on this Conder token from 1796 in Plymouth, England, which shows a double flyer wheel being used in “sail canvas manufactory.”

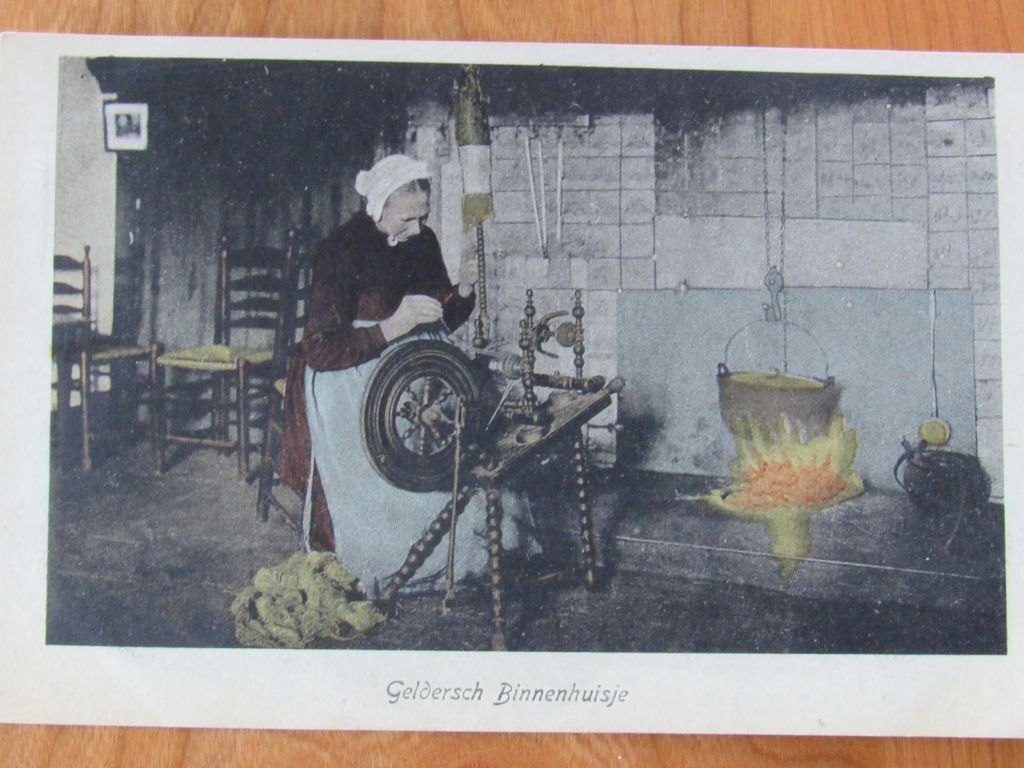

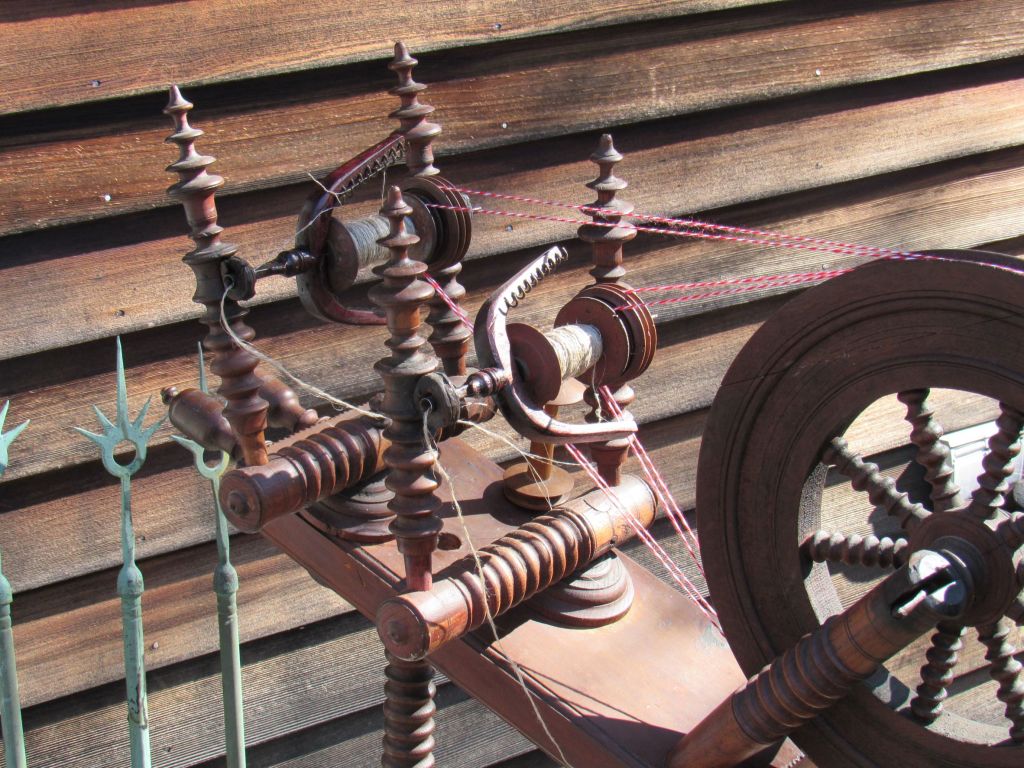

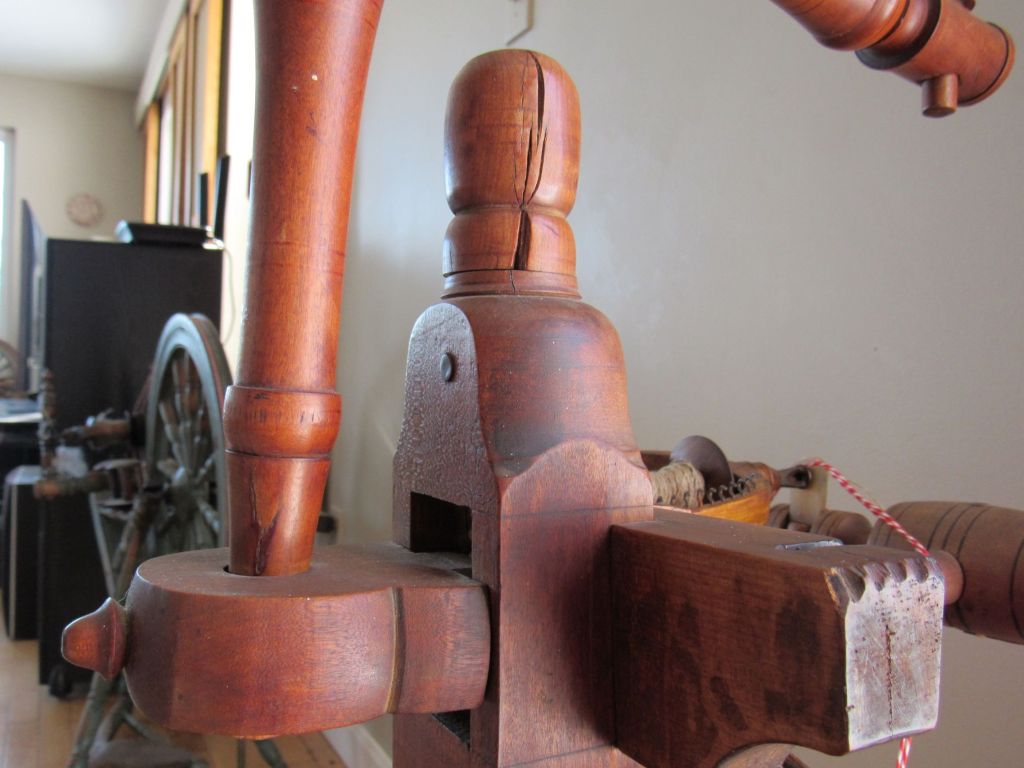

However they were used, they did come in several different styles. “T-top” is a wonderfully descriptive name, because this style wheel has a t-shaped support for the two flyers. It gives them an almost weightless, elegant look.

In contrast with the double table wheels, most of which are marked with the maker’s first initial and last name, the t-top wheels, when marked, tend to have initials only.

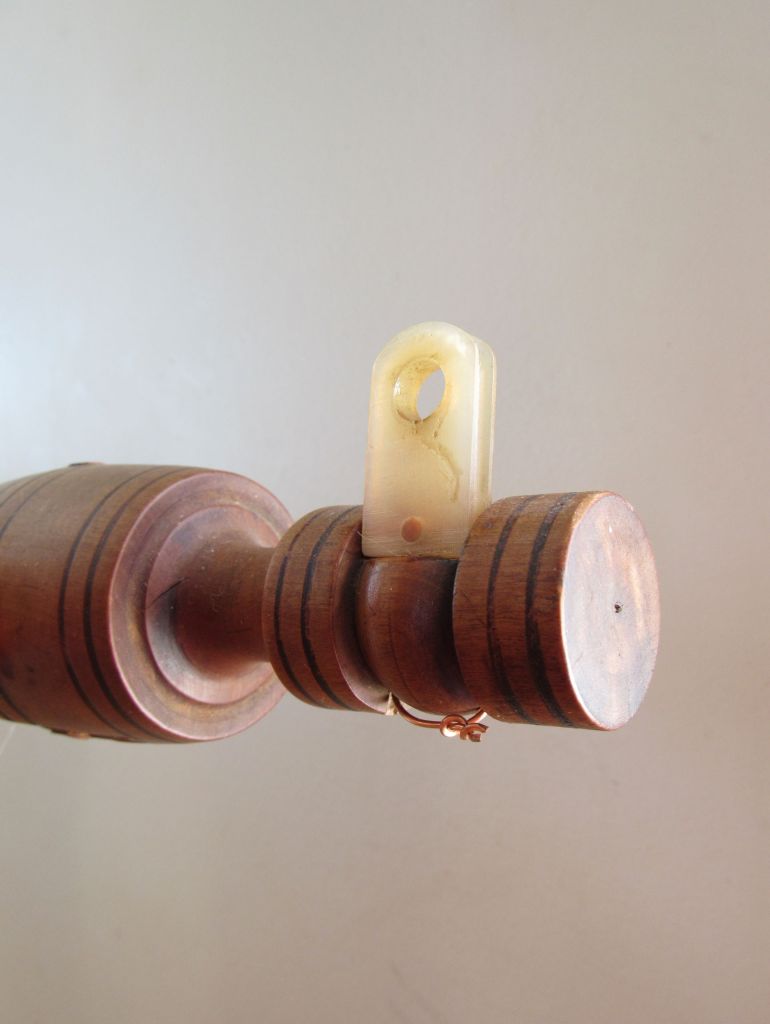

Examples have been found with “AT,” “TM,” “EB,” and “DS.” Why would the t-top wheel makers consistently use only initials? And who were they? Another mystery are the flyer bearings.

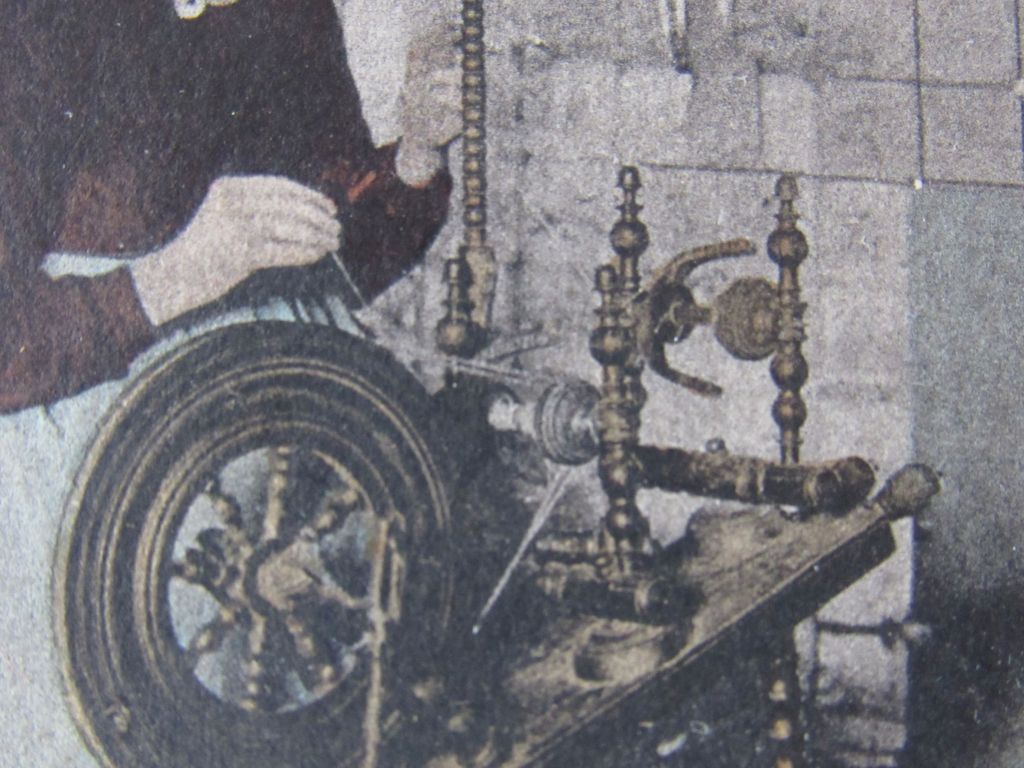

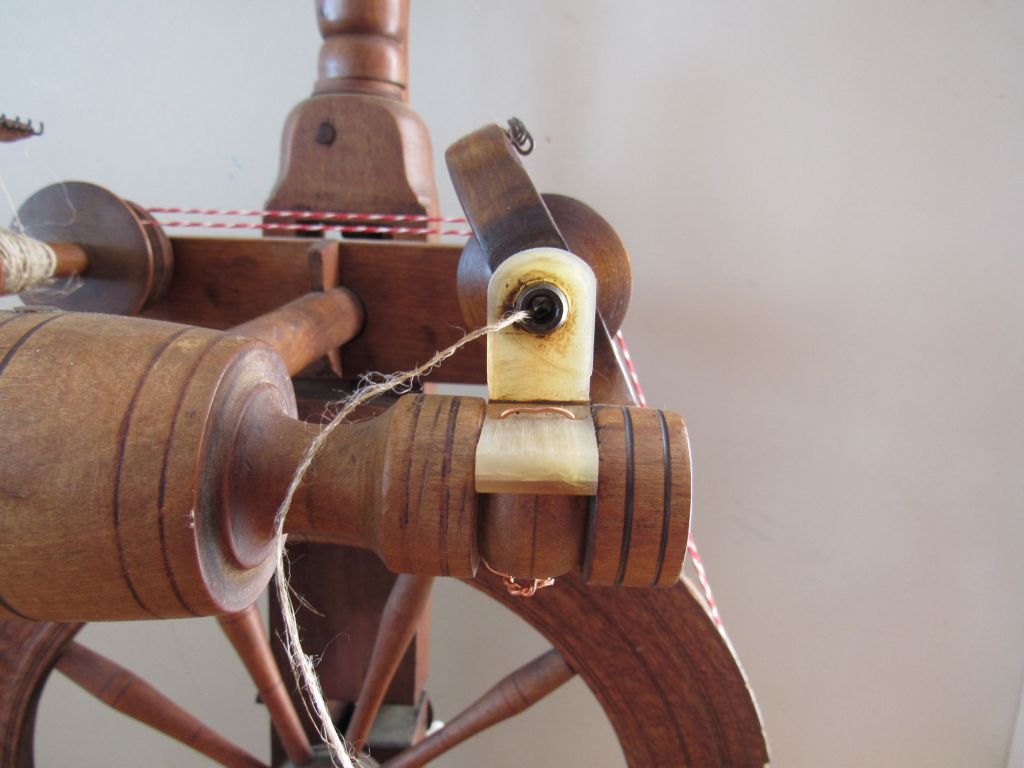

Apparently, they were often horn rather than leather. When I bought my wheel, both flyers were missing and there were no bearings at all. Where each bearing belonged, all that remained was a recessed flat space with two holes.

The other end of the flyer rests in a groove cut into the rear cross piece.

One side is marked with an “X,” which likely matched with a corresponding mark on one of the flyers. This is sometimes seen in double flyer wheels, although why it would matter which flyer goes on which side is not clear to me. Was each flyer slightly different for some reason?

There are small wooden pegs underneath that reach up into that groove. The peg tops are just visible at the bottom of the groove and appear to have some sort of hole or groove near the top.

The vertical tension screw has a keeper peg.

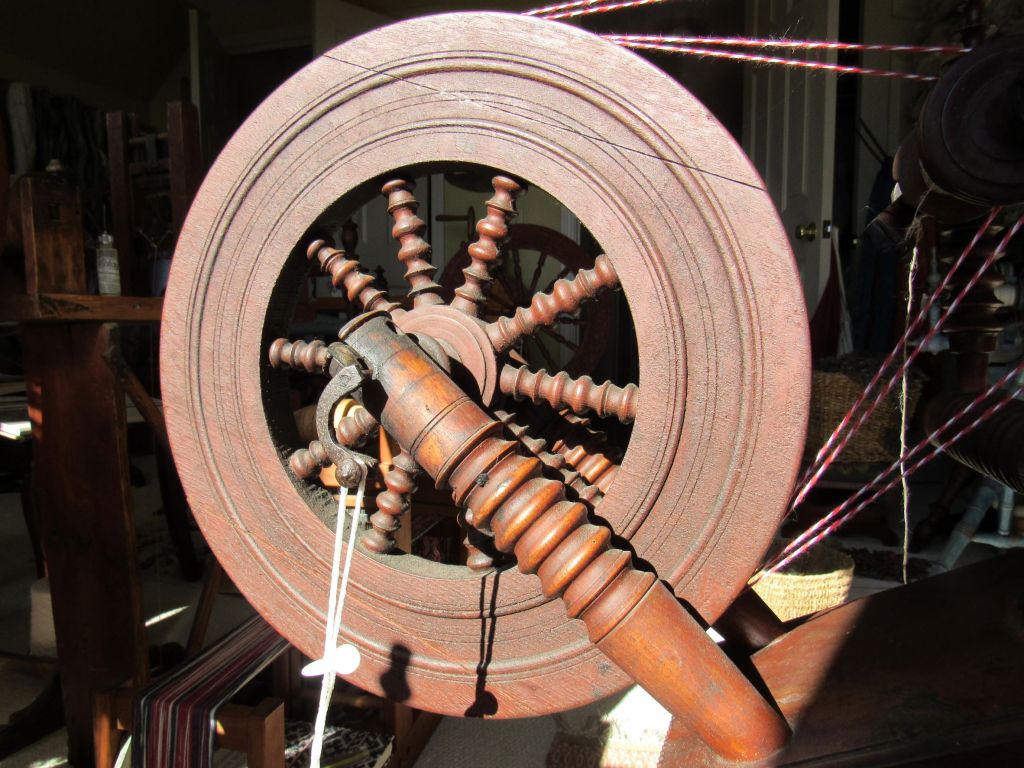

The spokes are cut to fit over a ridge in the drive wheel rim

and pegged through the outside.

The wood on the table is a little rough,

especially in comparison with the thoughtful decorative details on the rest of the wheel.

She is a very pretty wheel and, without flyers, she remained merely decorative for a year or so.

Then, one day I found a small flyer assembly that was a perfect fit. Similar to the wheel, the flyer looked barely used.

But there is an extra set of holes for the flyer hooks, which seems odd.

Why would the hooks be replaced if the flyer was little used? I decided to have another flyer made, along with some horn bearings, so that she could be spinning again.

And, she does spin. But, so far, I have not particularly enjoyed spinning on her. For one thing, she has a stubborn leg.

It falls out. Constantly. None of the usual fixes have worked so far. She also has a surprisingly fragile feel.

Most of my wheels obviously were designed for hard use and to stand up to wear and tear.

In contrast, this wheel feels as if she wants to fly apart.

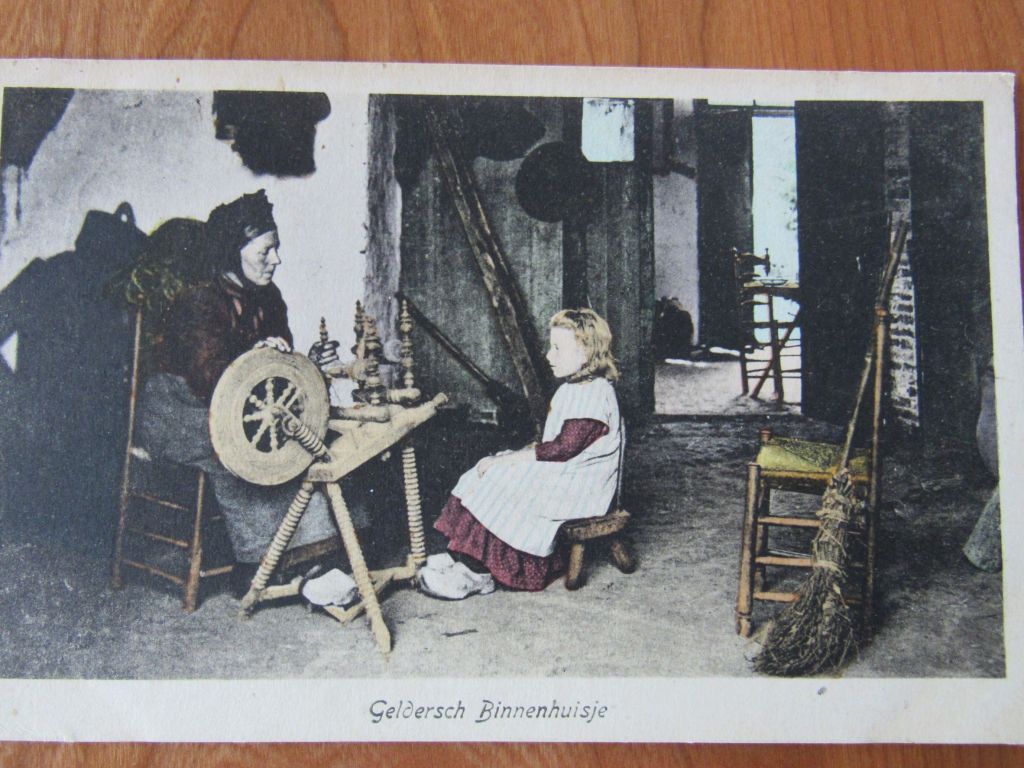

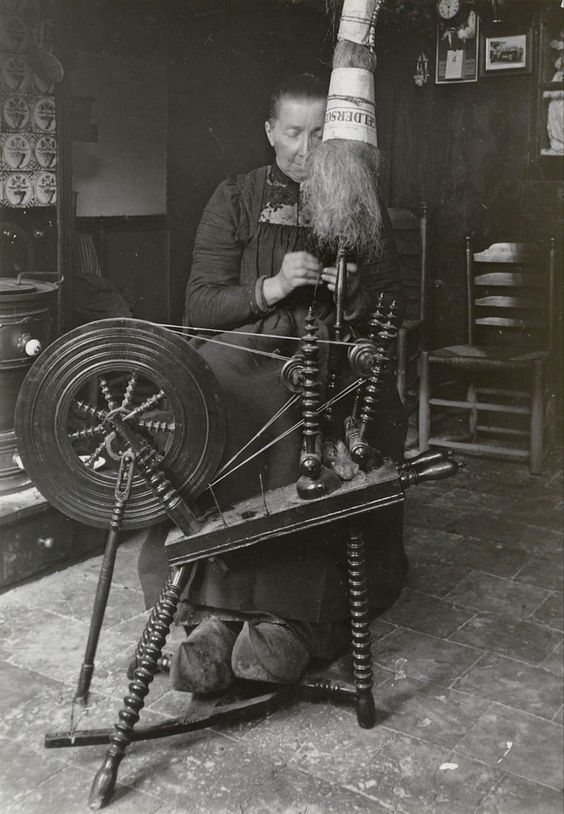

As for the spinning, I have become spoiled by “Truus,” my Dutch double flyer wheel. Truus has a horizontal set up, with each flyer on a separate tension system. I much prefer that to these vertical wheels, which have only one tension screw for both flyers.

I have not yet been able to get Henrietta to have the same uptake rate on both bobbins, which makes for frustrating double flyer spinning.

I am hoping that with more time and attention, we will get along better. In the meantime, she’s lovely to look at.

For more information see:

Taylor, Micheal, “A ‘T-Top’ Double Flyer Wheel,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue #64, April 2009.

Pennington, David A. and Michael B. Taylor. Spinning Wheels and Accessories. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2004, pp. 86-87.