Flax is amazing. It has been used by humans for fiber for about 30,000 years.

Fiber flax today, Linum usitatissimum, is a slender plant, often three feet or more in height, topped with a blue flower that bobs and sways in the wind.

Its stem contains long fibrous strands that, when separated from the woody parts, can be twisted or spun into strong, long-lasting linen thread. But getting from plant to linen is a laborious, exhausting process, made somewhat easier by tools developed over centuries. Fortunately, in New England, where I live, many of these tools can still be found in barns, antique stores, and at auctions.

Many European settlers in New England came from flax growing regions and brought with them the skills and knowledge for flax production. New England’s climate was well-suited for growing flax and during the 17th and 18th centuries, it was widely grown and processed by households for bedding, clothing, ropes, string, and sails.

It must have been a beautiful sight to see acres on acres of flax in bloom. But the work involved for a family to process enough for its own use is almost unimaginable to me. After processing my own flax for several years, I will never look at linen in the same way again. I am in awe of the fabric and the people who produced it, one backbreaking season after another.

I became intrigued with the thought of growing and processing my own flax after seeing a demonstration at Maine’s Common Ground Fair the year we moved here. Soon after, I read A Midwife’s Tale, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book based on the diary of a Maine woman, Martha Ballard. I found a complete copy of Ballard’s diary online and searched for all references to flax growing and processing to get a better idea of how it fit in to the rhythm of her year. http://dohistory.org/diary/1785/01/17850101_txt.html. When I planted my flax seeds the next year, I followed Martha’s schedule.

Flax is easy to grow in Maine and has thrived in my garden. I plant it in May and harvest it 90-100 days later, when the plant has turned a golden-yellow on the bottom third. The flowers only last a day and then rapidly turn into roundish seed pods, which change color from green to gold as they mature.

Flax also is valuable crop for seeds and seed oil, but seed flax is a different variety than fiber flax and does not grow as long and tall. Fiber flax is harvested by pulling it up, roots and all (the roots are small). It then is bundled and dried, usually by setting the bundles into shocks or by hanging them.

After it has dried, the seeds are removed—a process called rippling. This can be done by laying the flax down and crushing the seeds with a wooden mallet or flail or by using a rippling comb, also called a ripple.

Of all the flax processing tools, ripples are the hardest to find in New England. It was not until this summer that I found one, and I had already rippled the year’s flax.

So, I don’t have a photo of it in use. Instead, I took some stray flax plants that grew from seeds dropped in the garden while harvesting and used them in the photo to give an idea how it works. The ripple has metal teeth, nicely spaced to whomp off the seeds while allowing for a nice smooth motion pulling the plants through.

Two prongs at the bottom can be secured between or in boards and allow the ripple to be easily carried for use in different places.

There are initials “CW” in a corner on mine and some decorative lines and balls. I can’t wait to put it to use next year.

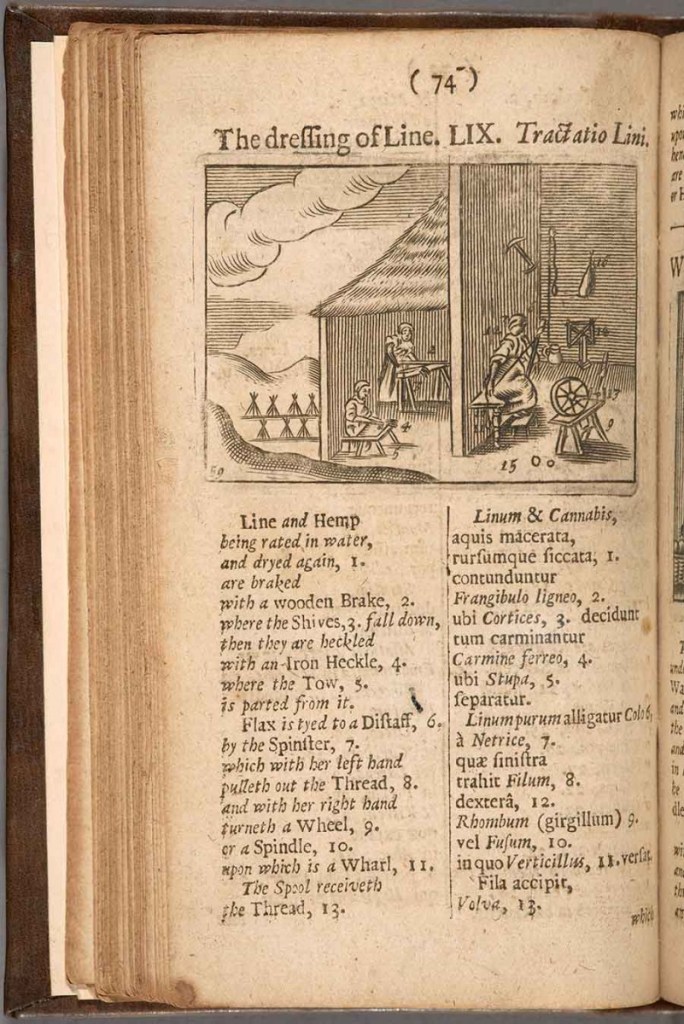

Rippling is just the start of processing. The next stage, retting, is a tricky one. Retting dissolves the pectins connecting the fiber bundles in the stem, allowing the fibers to be separated from the woody inner core and outer skin. It is essentially a bacterial rotting process, but must be handled carefully so that it doesn’t progress too far and break down the fiber itself. Traditionally, two types of retting were used—water retting and dew retting. I also use a third, less common method—snow retting. In water retting, the flax is submerged and weighted down.

It is the fastest, and smelliest, retting method, usually taking about 5 days for me in summer heat. For dew retting, the flax is laid on the grass and turned regularly. I usually dew ret in September and it can take anywhere from 10 days to three weeks, depending on the weather.

For the last two years, I have retted some of my flax on snow, laying it down when there is sufficient snow cover to keep it from touching the ground then leaving it there until snow melt—2 to 3 months.

Every type of retting produces a different color fiber—almost white for tub-retted, gray for dew-retted, and golden for snow-retted.

It is tricky to time the retting just right, but every year I get better at it. Once the flax is retted and dried again, it is ready for breaking–the process that removes the fibrous strands from the wood core and epidermis. The woody bits that break off are called boon or shive.

Mallets can be used for breaking but hinged wooden flax breaks (or brakes) are much more efficient.

They have a blade or blades on the upper arm that descend into grooves in the lower part, smashing the flax between them.

Most breaks are on legs, but some were designed to be used on a table. This break has three blades on top and four on the bottom. I bought it from a friend in Maine and another Maine friend has one that is almost identical.

Interestingly, there is one just like them from Lunenberg County, Nova Scotia, pictured in a book about early handweaving in eastern Canada, Keep Me Warm One Night (p. 28, photograph 6).

I have also seen a photo of one in Kentucky and some similar ones in Switzerland.

It is a good solid break, the crossbars on the legs make it easy to pick up and move around.

My second break appears to be much newer.

In fact, I suspect it may have been made in the 1960s or 70s. I bought it at an auction for $10.

The auctioneer had no idea what it was and called it a “farm implement of some sort, maybe it could be used to make pasta, ha, ha.”

It has two blades on the top and three on the bottom.

It is simple, sturdy and works well.

Each break has its own feel and way of working—both good, but different.

I also bought this beauty at an auction.

It had belonged to couple living on Rings Island near Newburyport, Massachusetts. Unlike most breaks, it is dated and initialed and has a seat. I have seen a few breaks with these seats and would love to know more about them. (see the update below) Breaking is rough and repetitive—hard on the back, the hands, the wrists, and the legs. It must have eased the burden to be able to sit on the bench. I like to think of it as an old woman’s break. Sadly, it is riddled with woodworm tunnels, so I only use it occasionally.

Finally, here is a little toy break.

I would love to know how old it is and for whom it was made.

After breaking, flax still needs to be scutched and hackled before it can be spun. Scutching knives and hackles come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and I will do later posts on them. In the meantime, there are wonderful books on flax for anyone interested. I only skimmed the surface here.

Burnham, Harold B. and Dorothy K., ‘Keep me warm one night,’ Early handweaving in eastern Canada, Univ. of Toronto Press, Toronto and Buffalo, 1972.

Dewilde, Bert, Flax in Flanders Throughout the Centuries, Lannoo, Tielt, Belgium, 1987.

Heinrich, Linda, Linen From Flax Seed to Woven Cloth, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 1992.

Meek, Katie Reeder, Reflections From a Flaxen Past, Pennannular Press Int’l, Alpena, Mich., 2000.

Merrimack Valley Textile Museum, All Sorts of Good and Sufficient Cloth, Linen-Making in New England 1640-1860, Merrimack Valley Text. Mus., North Andover, Massachusetts, 1980.

Zinzendorf, Christian and Johannes, The Big Book of Flax, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 2011.

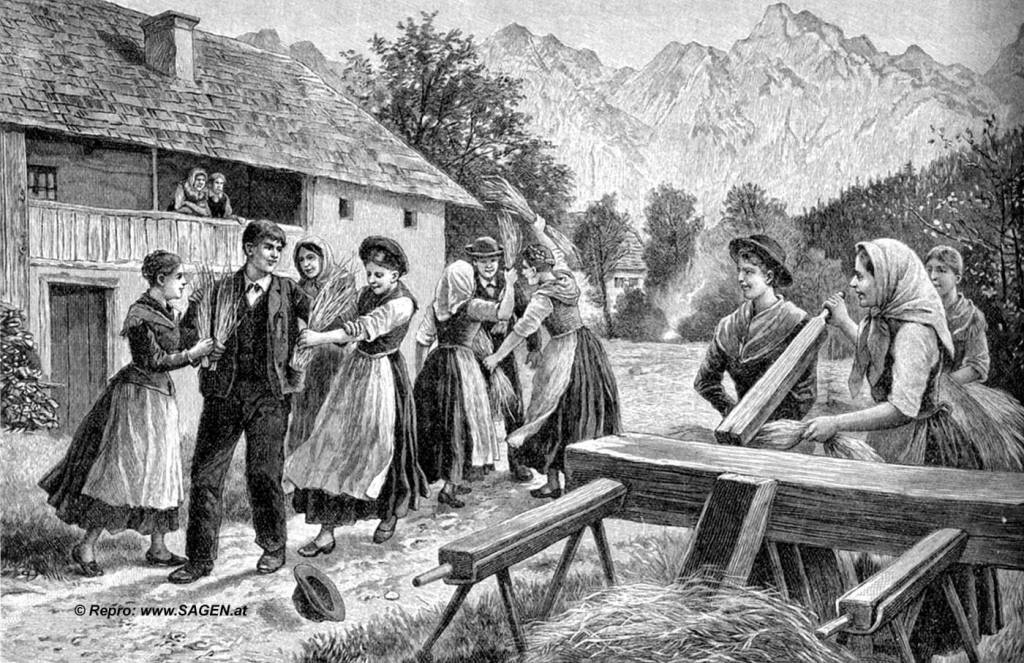

Update on October 1, 2021: Recently Christiane Seufferlein, who started the wonderful group, Berta’s Flax, on Facebook, posted this photograph of a woman using a seated flax break like the one I bought from Newburyport.

According to Christiane, this photograph was taken in the 1930s in the Bavarian region of Austria. She also sent me a photo of a similar seated break and scutching wheel from the Mühlviertel region of Austria. Similar scutching wheels were used in North America and there is a photograph of one from Pennsylvania in the post “Scutching Knives.”

And, finally, here is a drawing of flax processing in Austria with an intriguing multi-station flax break.

As Christiane explained, “There have been many customs when it came to flax processing. In Kärnten, one part of Austria it was common to celebrate the breaking of the retted flax. This task was done by the women if a farm and whenever a man came near he was ‘attacked’ with flax. The girls stuffed the little flax bundles in his collar and pockets and only stopped when he paid for his freedom. In the evening there used to be a dance in the barn.”

Thank you to Christiane for allowing me to use these photos and, especially, for her work in sharing the dowry flax of Berta, Rosa, Maria, and others to people around the world.