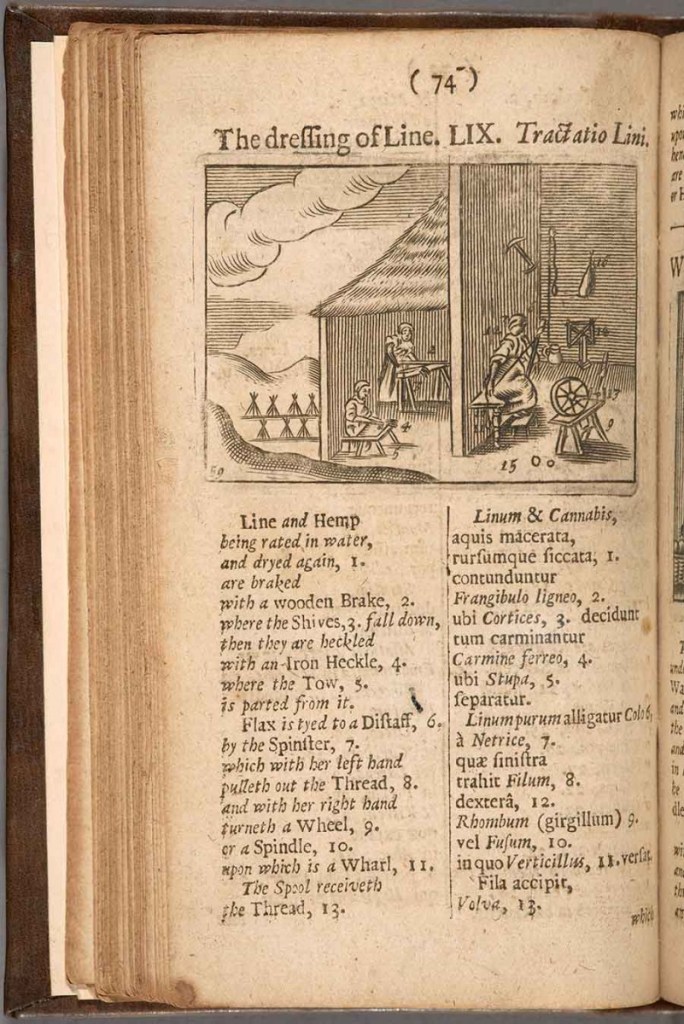

It is not easy to turn flax into linen. There are multiple steps, with marvelous names that evoke the Middle Ages—rippling, retting, breaking, scutching, and hackling.

In a previous post, I wrote about the first steps for processing flax into linen.

In short, after flax is grown and the seeds starting to mature, it is pulled and dried.

At this point, the seeds usually are removed

—a process called rippling–and the stalks are retted, so that the fiber can be separated from the woody boon or shive—usually with a flax break. For detailed explanations and photographs of these initial steps, see my previous post “A Ripple and Breaks.”

After breaking, the next step in most flax growing regions is the scutching process. Scutching helps further remove the woody boon and shorter tow fibers, while softening and aligning the long fibers for the final step—hackling (or heckling or hatcheling).

The term “scutching” derives from the Middle French word “escochier,” meaning to beat or strike. Another term for the process, “swingling,” similarly came from the Middle Dutch term with the same meaning, “swinghel.” And that is how scutching works, by striking the flax fibers at an angle to scrape away the bits of boon still clinging to the flax fibers after breaking.

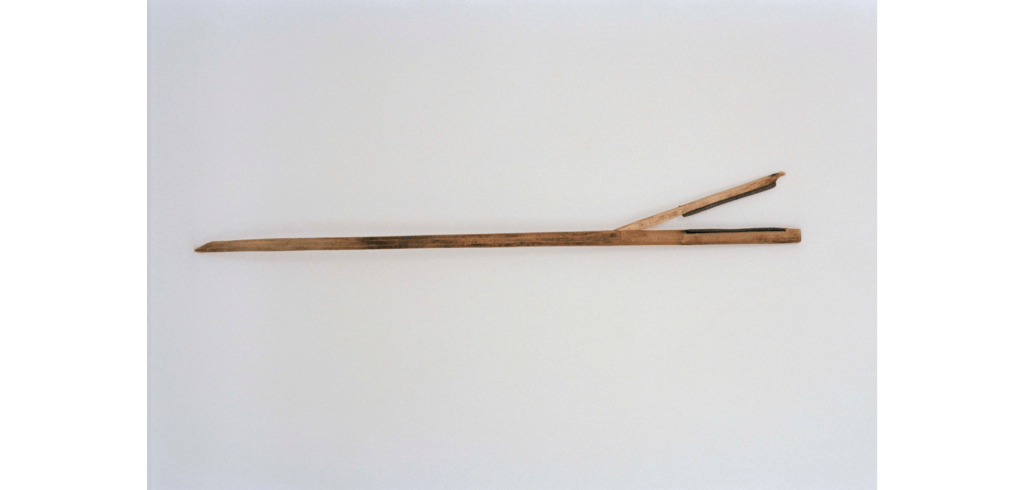

The simplest method is to use a wooden scutching knife while holding a bundle of flax against an upright board. As with most steps in flax processing, there are regional variations. In Sweden, for example, other tools were also used to remove the boon, a draga (puller), which looks much like a flax break with metal edges and a stångklyfta (cleft bar), which looks like a long pole with alligator jaws, again with metal on the edges. In some places, the scutching step is skipped altogether.

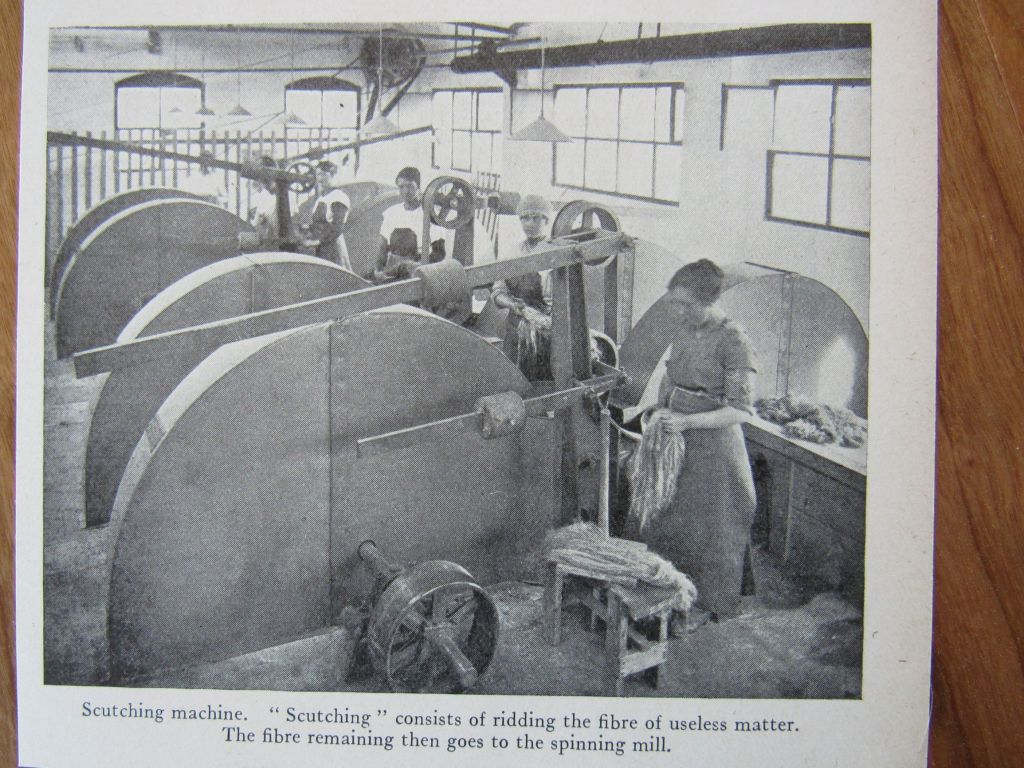

But in most flax growing regions in the 18th and 19th centuries, some version of a scutching knife was used. By the 19th century, scutching machines were developed. These had multiple blades on a turning wheel, powered by foot or, later, water.

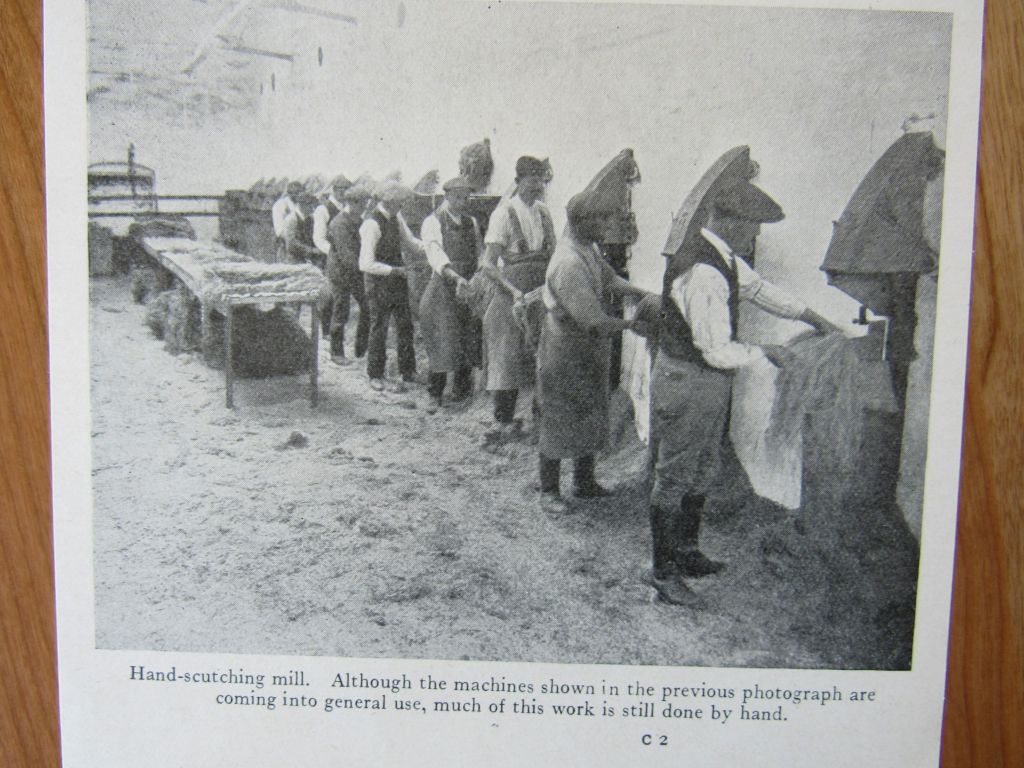

Eventually scutching machines were mechanized and in Ireland, scutching mills were commonly used by the mid 19th century. They were efficient and dangerous, with fast whirring blades always a threat to cut off fingers and hands, or even entangle long hair.

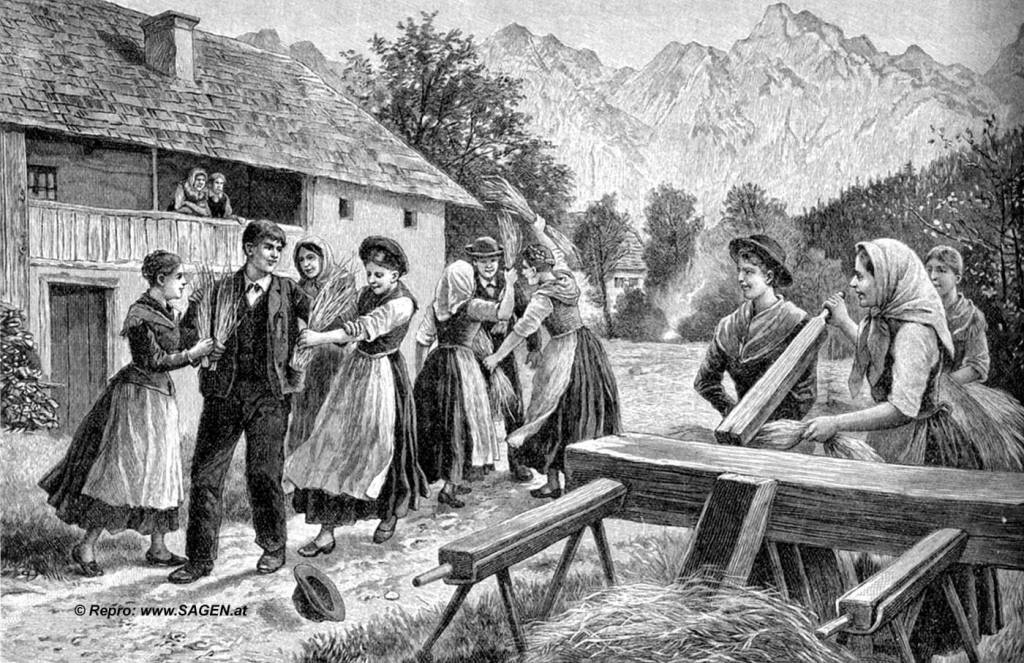

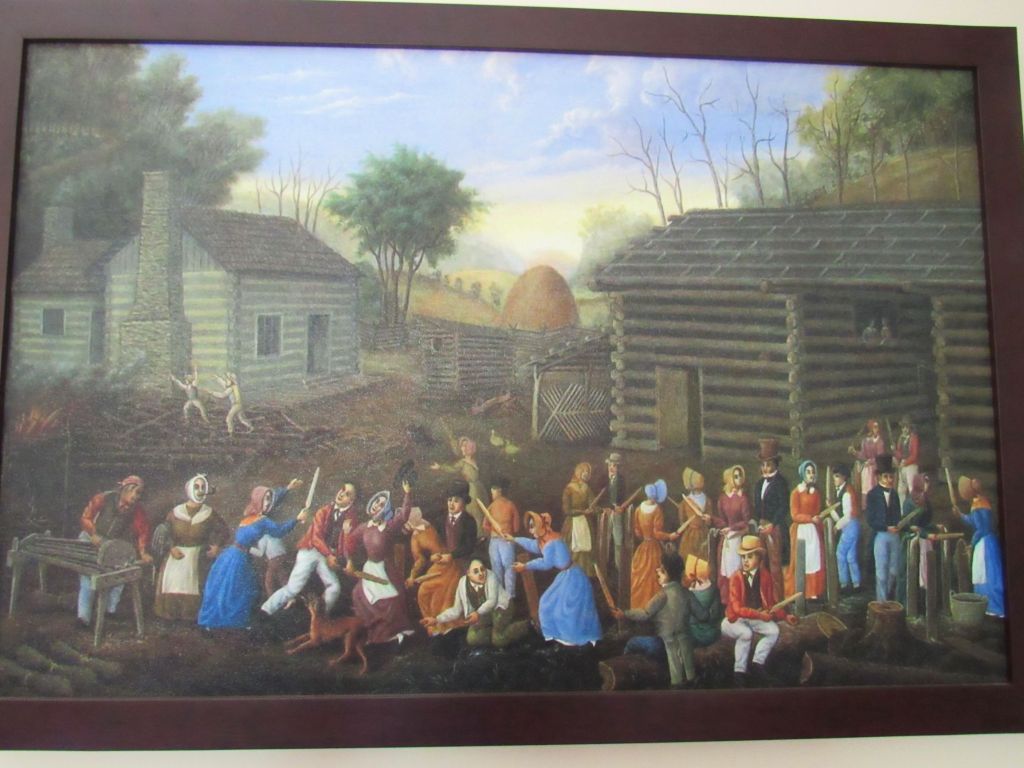

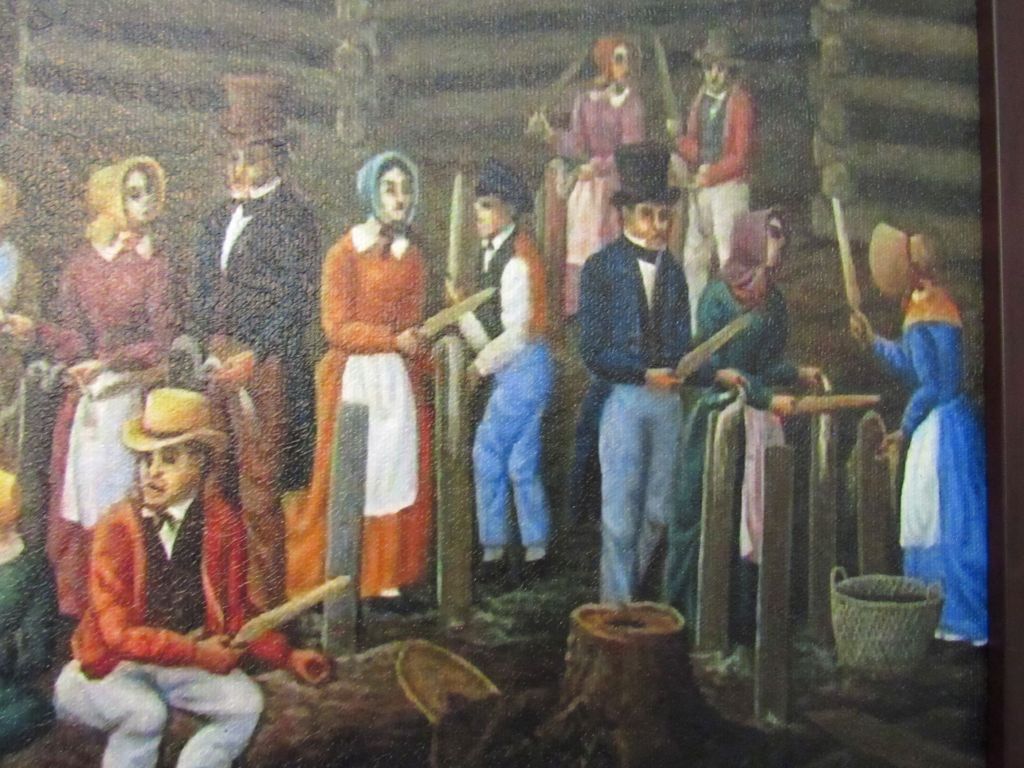

Before mechanization, the biggest danger in scutching may have been over-imbibing at a community scutching bee, as depicted in this wonderful 1885 painting by Linton Park.

Sober scutchers on the right, working diligently,

While those who have had a few drams are getting rowdy, brandishing their scutching knives as weapons.

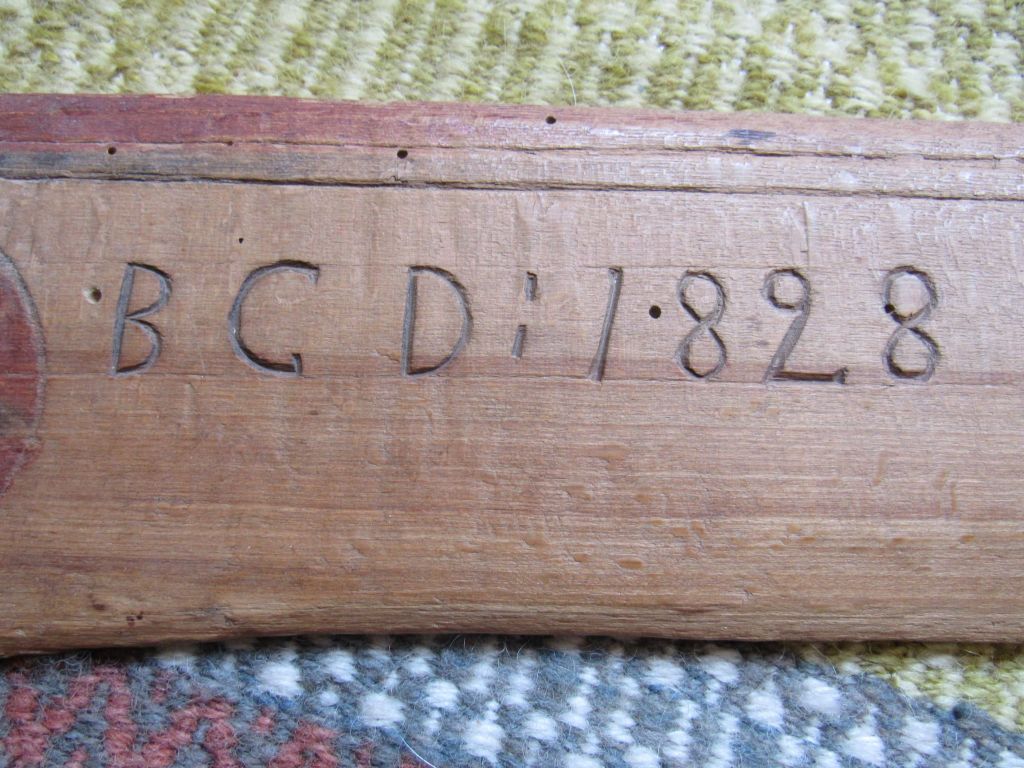

As for scutching knives themselves, they ranged from extremely basic to elaborately decorated. They come in various shapes and sizes and usually are not too heavy, so that they can be used for extended periods without putting too much stress on the wrist and arm.

In New England, it is hard to find scutching knives these days.

Probably because they were plain and utilitarian and would have been burned or thrown out once flax was no longer produced.

Those that have survived in New England usually seem to have the handle on the upper part of the blade. Those from Pennsylvania, on the other hand, more often have handles in the center of the blade.

Of course, scutching knives that were decorated were less likely to be thrown away and some truly beautiful ones have survived.

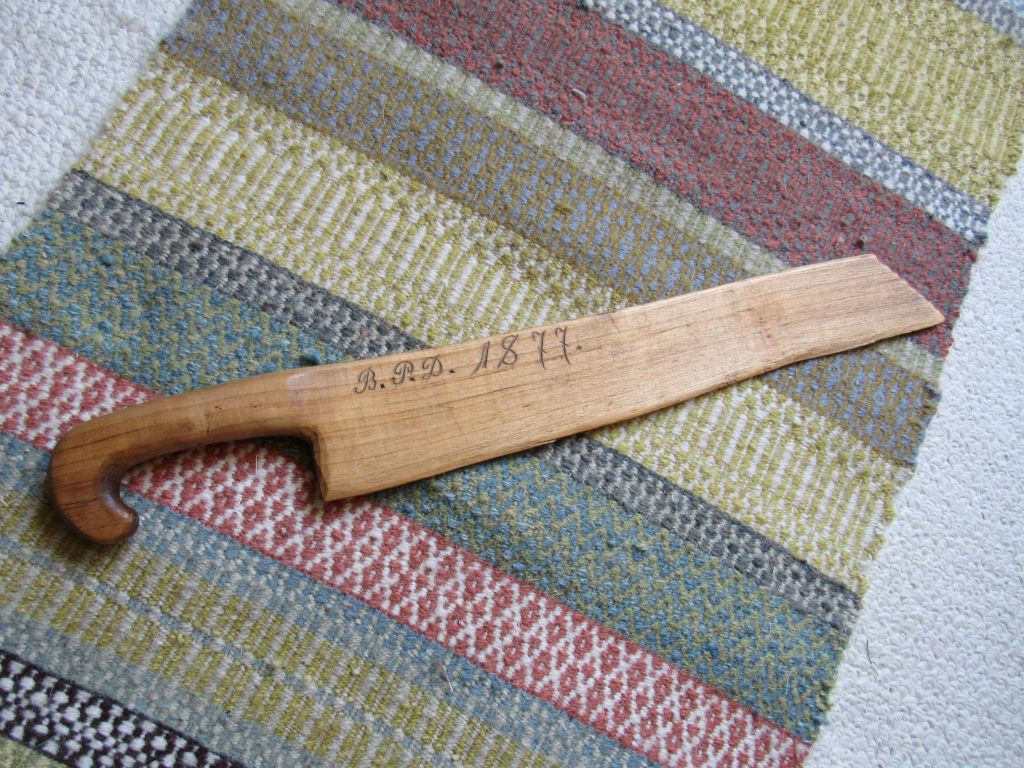

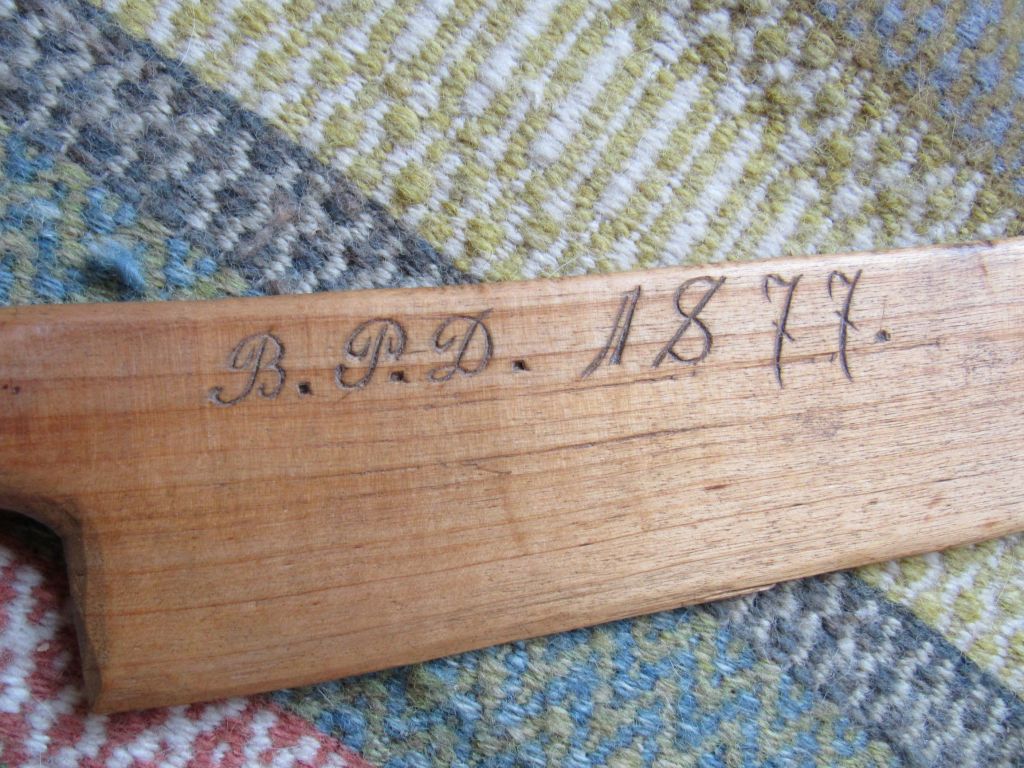

These two initialed knives came from a Pennsylvania auction.

They carry the same initials.

Unfortunately, I do not know whether they were originally from Pennsylvania or Europe or Scandinavia. Having a “D” as the last initial suggests Scandinavia for a “daughter” name, but the decorative compass stars are typical of Pennsylvania and Germany.

Another two that I bought as a pair are also a mystery.

Both have “D” as the last initial, so I am assuming they are Scandinavian, but, other than that, I have no evidence as to their origin.

They have lovely details.

I use both of them regularly—they are light but work well and fit my hand as if they were made for it.

At the other end of the spectrum from the simple knives of New England are the elaborately painted ones from Scandinavia, especially Sweden.

They were often bridal gifts,

usually from the husband-to-be, typically with initials and dates, and painted with flowers.

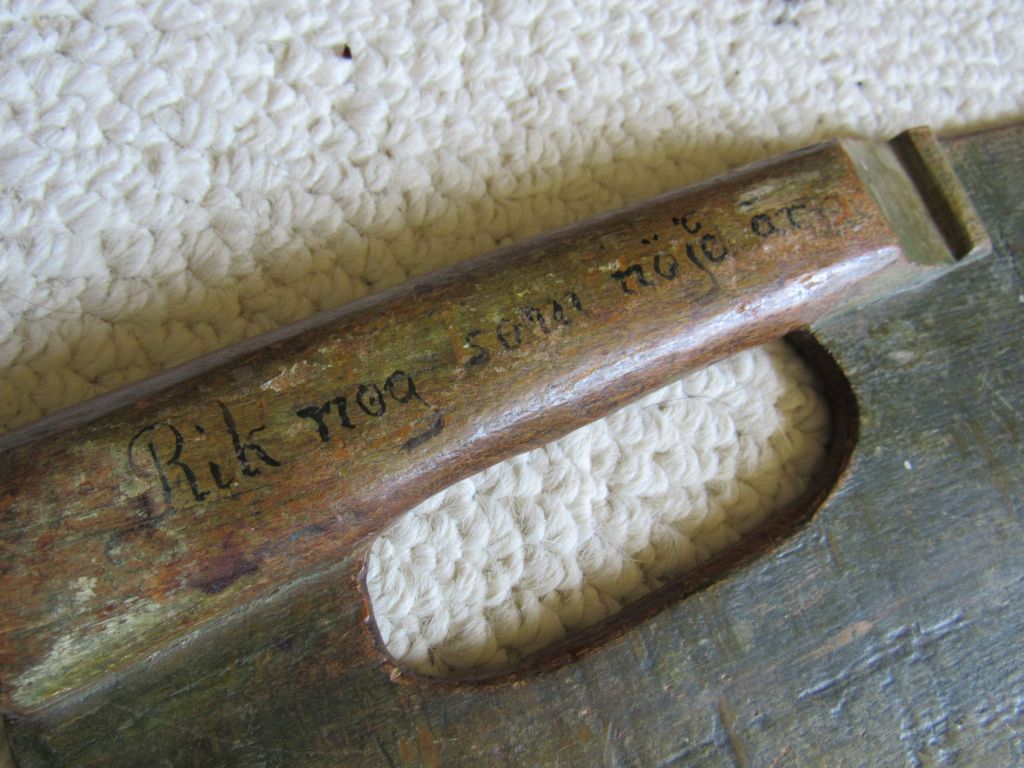

But my favorite has no initials or dates. It is much more personal than that.

It depicts a woman standing in front of a house with a birch tree at the edge of a lake, with amazing details such as the rocks and grasses at the lake edge.

She is exquisitely dressed in the traditional costume from Rättvik in the Dalarna region of Sweden.

Painted on the handle is “Rik nog som nöjd är,” which roughly translates to “you are rich enough if you are content” (Swedish speakers, please correct me if I am wrong). I am in awe of this knife and the history it carries with it.

References:

Burnham, Harold B. and Dorothy K., ‘Keep me warm one night,’ Early handweaving in eastern Canada, Univ. of Toronto Press, Toronto and Buffalo, 1972.

Eliesh, Rhonda and Van Breems, Edie, Swedish Country Interiors, Gibb Smith, Layton, Utah, 2009 (p. 16).

Dewilde, Bert, Flax in Flanders Throughout the Centuries, Lannoo, Tielt, Belgium, 1987.

Heinrich, Linda, Linen From Flax Seed to Woven Cloth, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 1992.

Meek, Katie Reeder, Reflections From a Flaxen Past, Pennannular Press Int’l, Alpena, Mich., 2000.

Merrimack Valley Textile Museum, All Sorts of Good and Sufficient Cloth, Linen-Making in New England 1640-1860, Merrimack Valley Text. Mus., North Andover, Massachusetts, 1980.

Zinzendorf, Christian and Johannes, The Big Book of Flax, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 2011.

The blog “Josefin Waltin Spinner.”