Although these three pieces are now in new homes, I want to include them in this blog because their unusual features should be documented for future reference.

THE REEL

The first, a reel I named “Annabelle,” came as a package deal with two wheels from Canada. I have no idea if the reel is from Canada, too. Given that the reel’s shiny glory is a metal bell, and metal was incorporated into many Quebec wheels, it is possible.

On the other hand, most (but not all) Quebec reels, called “dévidoirs,” unlike this one, are horizontal, barrel style reels, so it may not be from Quebec at all. Sadly, its origin remains a mystery. Its vertical design and counting mechanism is generally known as a clock or click reel.

Except in this case, the rotations are marked not by a click but by a ringing sound, because, upon 40 rotations, the wooden clapper hits a bell.

It is a louder and more pleasing way to count rotations, but I suspect having metal work done for a reel was not worth the extra expense for most people.

A shame, because it is lovely and practical feature. And, very rare.

THE WHEEL

The second out-of-the-ordinary piece, a great wheel I named “Felice,” was the wheel that hooked me on great wheel spinning.

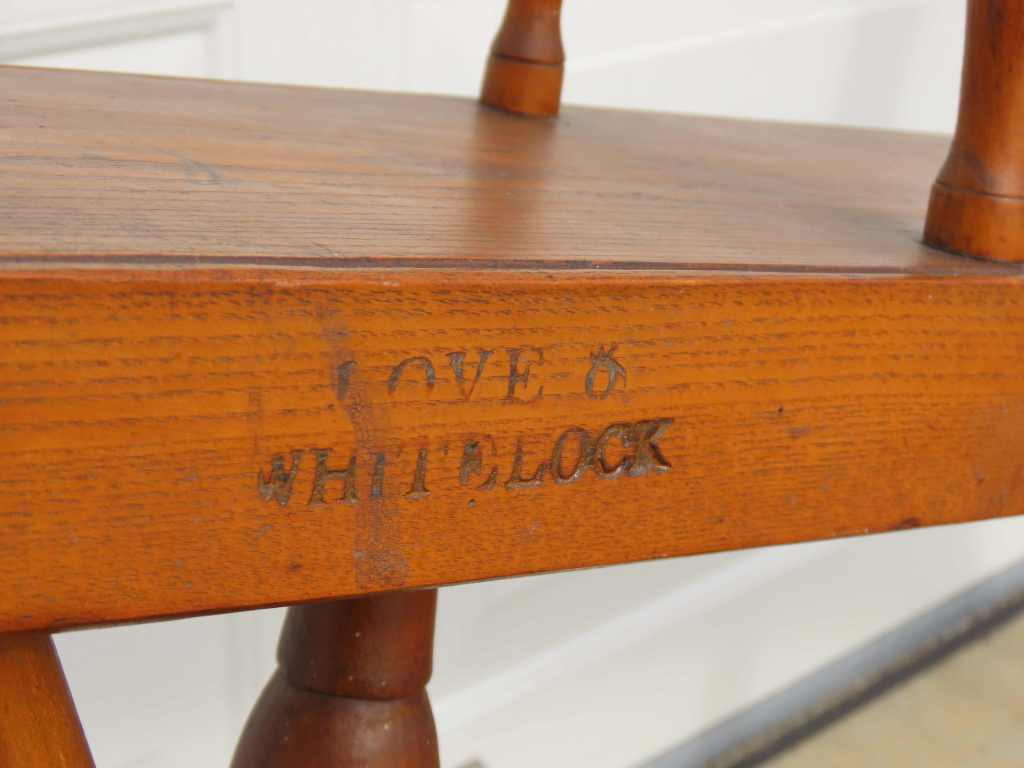

I bought her in southern Maine. The seller had, in turn, bought the wheel in New Hampshire from a woman who said it was Shaker. While the beauty, simplicity, and craftsmanship would fit well with the Shaker approach to design and construction, I have not seen any evidence that Shakers make wheels with features similar to this one.

The legs are chamfered rather than turned.*

The table also has transitional, chamfered bottom edges.

The wheel post has a perfectly fitted thick horn collar, a feature found on some early Shaker wheels.

The drive wheel rim has beautifully made joins.

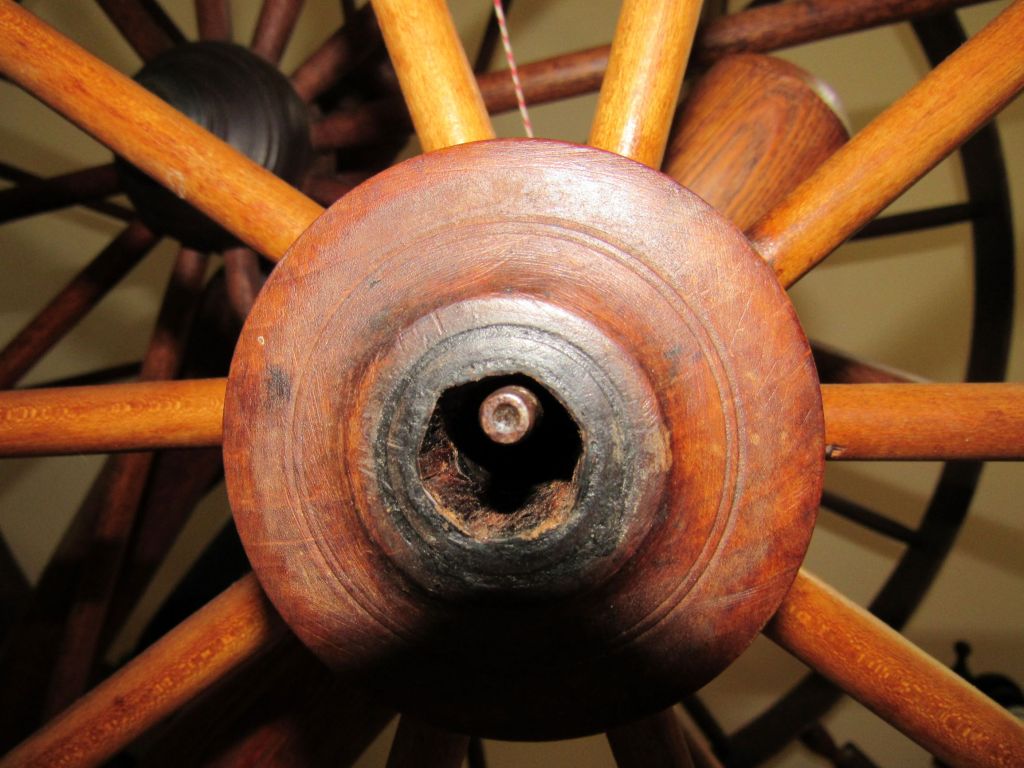

My favorite feature, though, is the hub, which is a perfect pear shape. I have only run across one other wheel like this one. It was found in Peachum, Vermont.

In my mind, these wheels are more beautiful than the typical Shaker great wheels. Mine also was a joy to spin on.

THE LOOM

Finally, another piece that may or not be Shaker is a very unusual two-person tape loom. I wrote an article about it for the Spinning Wheel Sleuth Handloom Supplement Issue #24, but this post will supplement the article with more photographs for those curious about this wonderful little loom.

It came up for auction near me last year and I fell head over heels for it at the auction preview. Designed for two people to weave simultaneously, with a petite, pleasing design, what put it over the top was that it was in fantastic condition, with string heddles and reeds made of actual reed.

It is only 39 ½ inches tall and 13 ¾ inches wide, but big enough for two people to weave tapes at the same time. It has no space-hogging treadles, which allows for a compact footprint. Each side has two shafts, connected by an overhead pulley.

Each shaft also has a cord running down to a lower pulley and then to an upper pulley,

ending with a wooden knob which the weaver pulls to raise each shaft.

Each side has its own warp and cloth beams, with cords for attaching the warp. Interestingly, the cords have water stains around them even though the rest of the loom shows no water damage at all.

One possible explanation is that the cords were moistened to make them swell and have a tighter grip on the beam when weaving. I found that without wetting the cords or otherwise securing them, they tended to slip around the beams when under tension.

The warp beams are held in place with wooden pegs and the cloth beams have metal ratchets and pawls.

The reeds in the overhead beaters have some newer cord on them, indicating that they have been repaired or replaced.

They also appear to be taller than the original reeds, based on the darkening of the wood on the beater sides.

The loom came with two extra pieces that were a total mystery to me.

It turns out that the piece with the prongs is a stretcher used to tighten webbing when making chair seats. The other piece, which looks very old, is something I believe was used to hold the reed in place for sleying. But, that is just a guess.

This treasure of a loom was well-cared for and apparently well-used. There are even numbers scratched on the loom top—24, 22, 24—presumably to keep track of something.

The auction house said that the loom came from the Baxter estate in Benton, Maine. Wildly curious about who would design and use a two-person tape loom, I started researching it right away and found that several have turned up. One other, just like it, but in much worse condition, was at the Fort Ticonderoga Museum and pictured in Bonnie Weidert’s book “Tape Looms Past & Present.” (photo 2-22, p. 24). A little research revealed several others—but designed for a single user—at Hancock Shaker Village Collection (1986.024.0001); Enfield Shaker Museum (2018.51); Marshfield School of Weaving Textile Equipment Collection (1959.1.12); and Jeanne Asplundh’s collection, photographed in “Spinning Wheels and Accessories” (fig. 14-67, p. 182).

Finding that two of the looms were at Shaker museums, I dove into research to see if there was an established Shaker connection (more on that in the SWS article). Ultimately, I could not find evidence to either prove or disprove that these were used by the Shakers.

The looms would be perfect for weaving the large amounts of the tape used by Shakers for chairs but the only documented Shaker chair-tape looms that I could find are a different style. If not Shaker, would they have been used in some other institutional setting such as a rehabilitation facility or a school? Having hand-operated looms would make sense for those unable to use their legs or for short-legged children.

Whatever its history, I am just thankful that it was preserved with such care so that it can be appreciated by us and future generations.

Page, Brenda, “A Two-Person Tape Loom,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth Handloom Supplement, Issue #24, April 2024

Weidart, Bonnie R., Tape Looms Past and Present, 3rd edit., Bonnie Weidert, Henrietta, NY, 2012

Pennington, David & Taylor, Michael, Spinning Wheels and Accessories, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, 2004

*I refer to pieces with multi-angled faces as “chamfered.” While I understand that others use the term to refer to 45 degree angled edges, until I learn of a more fitting term for the multi-angled faces that we find on legs, spokes, and supports of wheels and reels, I will continue to use the term chamfered.