Around the time that I picked up Polly, the Thomson bobbin winder in the previous post, I also bought a Hannibal Thomson great wheel.

It’s funny how related wheels often seem to come out of the woodwork in waves. None in sight for years and suddenly three pop up within weeks of each other.

This wheel was for sale in Waterboro, Maine—about sixty miles south of Turner, where Thomson made his wheels. Just as with Thomson’s flax wheels and bobbin winders, the Shaker influence is obvious in the overall design.

It could almost be mistaken for a Shaker wheel with its pewter collar, clean lines, and beautiful wood.

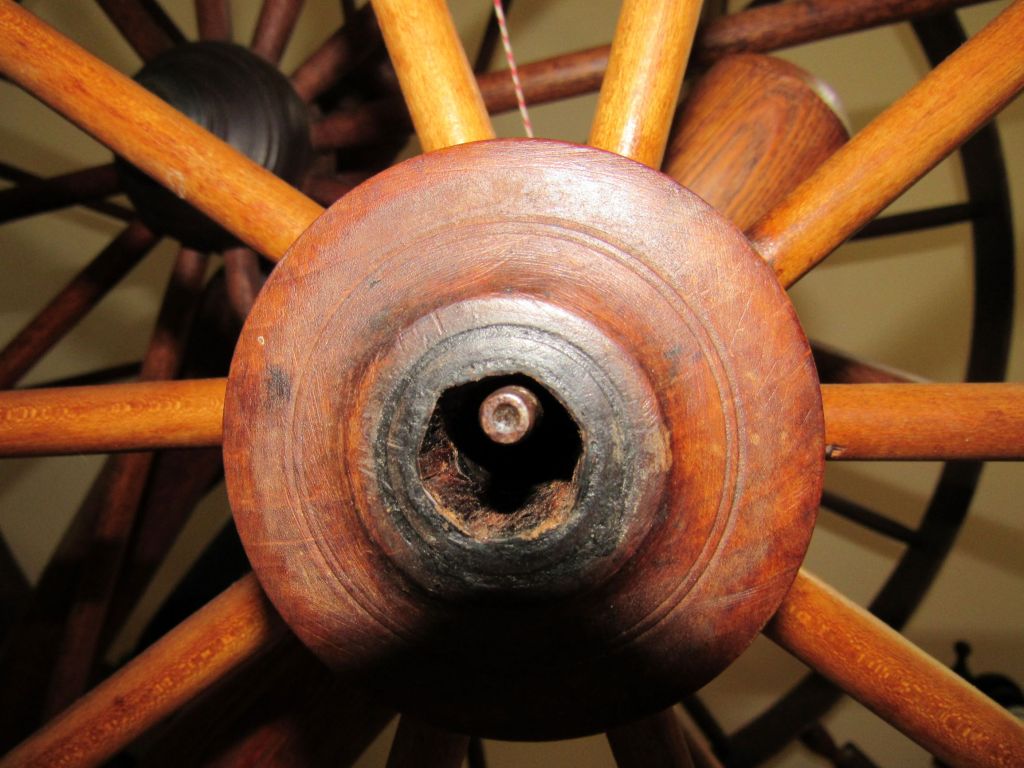

But it has Thomson’s imprint, too, in the collar’s scallops,

his signature spokes,

the fine decorative scribe lines,

and the table-top maker’s mark.

The nail pattern on the drive wheel join is the same with this wheel and Thomson’s bobbin winder.

Over time, this wheel has acquired its own particular oddities—missing bearings, surface scratches, and a strange leg. It’s fairly common for old great wheels to lose their hub bearings. This one was bearing-naked front and back, leaving a gaping hole around the axle and no support for the poor drive wheel.

The original front bearing appears to have been six-sided where it met the wooden hub, which is not unusual for this time period. New bearings can be made from various materials, including metal and plastic, but I’m always in a hurry to see how a new wheel spins, so usually just fold some sturdy leather in there and give it a go. The leather works great, which invariably means that I leave it in and new bearings plummet to the bottom of the wheel-repair priority list.

Without looking carefully, it’s not obvious at first that there are fine scratches over many parts of the wheel. The close-up photos really make them apparent.

I’m guessing that someone had a vigorous sandpaper workout on this wheel to clean it up at some point and that’s what left the scratches. If anyone has other theories, I’d love to hear them. I kind of like the scratches—they are subtle to the naked eye and are part of the wheel’s history—remnants of some person’s time and attention on the wheel. I view them as fine wrinkles on a beautiful face.

The strange leg is more of a mystery. First, a matter of terminology. I believe it’s fairly standard to refer to the legs on the right side of wheel (facing the wheel from the spinner’s side) as the back legs. I just don’t get that. Since great wheels look like magnificent herd animals ready to go bounding down hill wheel first, the legs on the wheel end should be the front legs, right?

So, since what seem to be front legs to me are back legs to most, I will refer to great wheel legs as the “uphill side” and “downhill side” legs. With the downhill side legs on this wheel, the spinner side leg is about an inch longer than the far-side leg and it splays at a slightly different angle. In some wheels, such leg differentials are purposeful, to make more room for the spinner to walk back and forth. I believe that is the case here, since Thomson’s bobbin winder has a similar leg, but the difference in this case may be exaggerated due because the leg does not seem to be set properly in its hole.

There is an unstained portion of the leg showing below the hole, which indicates that it once was more deeply set. On the other hand, the leg hits the floor at the proper angle, the table isn’t askew, the leg is clearly a Thomson leg, and the leg is tightly wedged into its hole. In any case, it gives the wheel a distinctive look.

The wheel has scribe marks for setting the angles of the spindle support and a peg to keep it from pulling out. Some Shaker wheels have similar marks and pegs.

In comparing this wheel to my other great wheels, the table is quite narrow—only a little over five inches wide—

and the drive wheel is high and wide of the table, especially in comparison to the Connecticut wheels (previous posts “Mercy” and “Big Bear”), where the drive wheels ride directly over the table, with little clearance.

Despite the differences, the height of the hubs is fairly consistent with all the wheels, with only about an inch differential.

This wheel came with an accelerated head made by Fred B. Pierce & Co. Accelerated heads were first manufactured in the early 1800s to increase spinning efficiency and output.

They are often referred to as “Miner’s heads,” because Amos Miner had an early patent on the design. Miner and others manufactured these wildly popular heads through the 19th century, with the Pierce family in New Hampshire dominating the market from about 1850 to 1900.

As an example of their output, Benjamin, the father, oversaw the manufacture of more than 60,000 heads in 1865 and many heads that we find today have a Benjamin Pierce label. Benjamin’s son Fred took over the business and the heads with his label were manufactured between 1882 and 1890.

That means the head on this wheel is relatively new compared to most. That may be why the corn husk bearings are still in good shape.

As a bonus, this wheel came with a wheel finger, also sometimes called a wool finger, wheel boy, or wood peg.

These were used to turn great wheels and bobbin winders, placing them on the spokes and giving greater reach and a break to hands, I guess, which must have gotten pretty stiff, achy, and arthritic over time.

Some great wheels will show wear on the spokes from use of a wheel finger, but this one doesn’t. The finger itself, however, has a good deal of wear, creating a lovely curve where it goes from the hand-holding hefty part to the narrow neck that hugs the spoke.

This finger spent a lot of time in someone’s hand.

For more information on Hannibal Thomson, see the previous post, “Polly,” and the references there.

My resources for information on Pierce accelerating heads:

Ramer, Alvin, “Accelerating Wheel Heads: A Comparison,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth 54 (October 2006).