Several of my wheels have forged friendships. One of the earliest and best of those wheel friendships came through Granny Ross. When the wheel came up for sale in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, a woman on Ravelry, Sherran Pak, posted the wheel’s photo, noting some similarities to the McIntosh wheels.

The seller said that the wheel was not in spinning condition and, although Sherran was initially interested in the wheel, she decided not to buy her because of the need for repairs and the difficulties in getting the wheel to her home in the Midwest.

I did not know Sherran and was uncomfortable pursuing the wheel, knowing how much she liked it. So, I contacted her and after her assurances that she was not interested and that I should go for it, I then contacted the seller.

The stars seemed to be aligned because the seller said that he would be taking a trip down to Maine in about a month and could bring the wheel with him. As it turned out, the meetup did not work out and I ended up, ultimately, finding a wonderful woman on Ravelry who, on her annual trip to Cape Breton, was willing to meet up with the seller and railroad the wheel down to me.

During the months it took to get the wheel, I got to know Sherran. Although I still have not met her in person, we have been continually in touch over the years, and she became a friend. She kept a lookout for wheels in the Midwest that might interest me and I helped her out (although to a much lesser extent) with wheels in my part of the world.

Some of my most treasured wheels came my way because of Sherran. She found them, picked them up (even waiting in line at an estate sale during covid), fostered them, arranged railroads, and sent them on their way to me. I am very much in her debt and am so glad that I have gotten to know her. And, it is all thanks to Granny Ross.

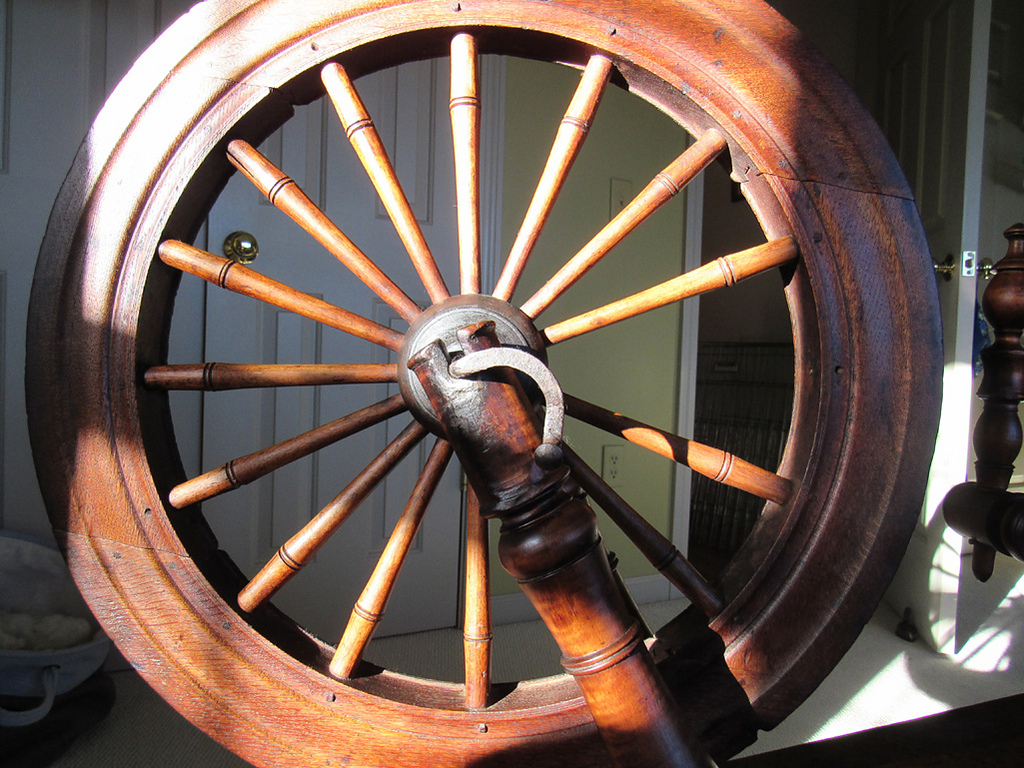

When Granny Ross finally arrived here, it was apparent why the seller said that she was not in spinning condition. The drive wheel had been seriously damaged, with a bent axle, spokes that had broken right off, with some clumsily re-glued. It looked as if someone heavy had stepped right on the drive wheel while it was on its side on the ground. I could just imagine the crunch of broken spokes.

Although I do not have photos of the drive wheel when it arrived, trust me, it was a mess. The treadle also was worn to the point of no return. The drive wheel damage was well beyond my repair capabilities, so I shipped it off to wheel-repairer extraordinaire, John Sturtevant. In the meantime, George crafted a beautiful new treadle with strong graining to match the legs.

When the drive wheel came back from John, it looked as good as new. I could not wait to try it out, interested to see how the heavy double rim would spin. I tend to like heavy drive wheels, with their sweet momentum, and Granny Ross did not disappoint. She became one of my favorite spinners.

She is a bit of a puzzle, though. Overall, she has a Scottish look.

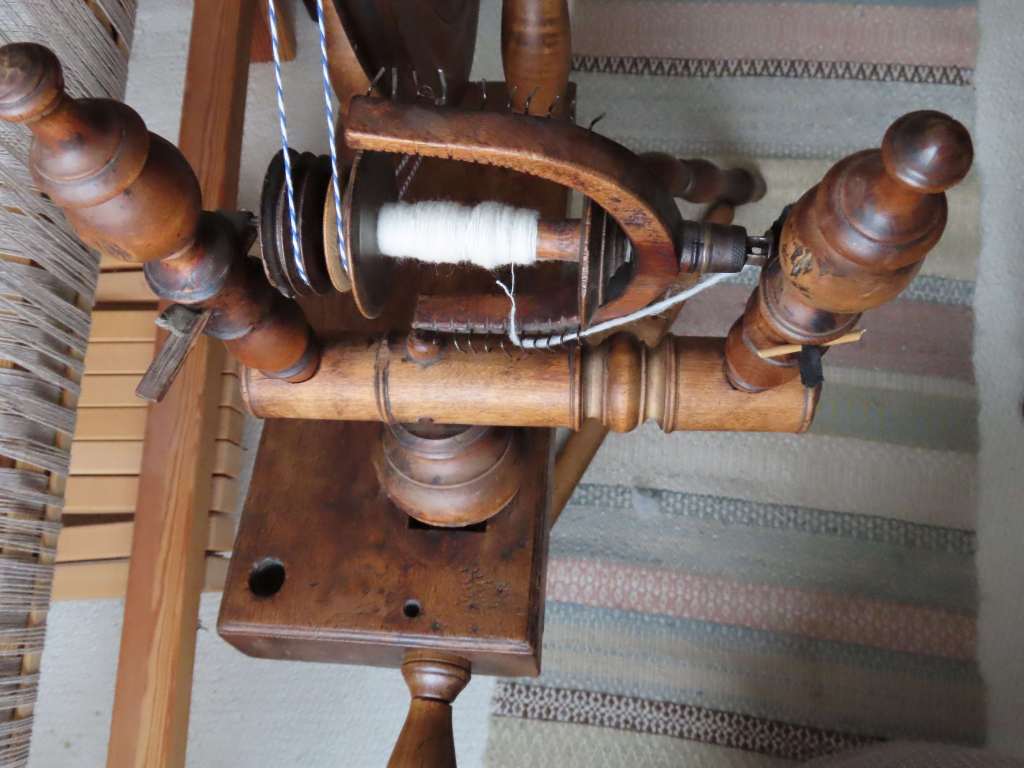

As Sherran noted, she shares characteristics with the McIntosh wheels, including a spoon-shaped end to the treadle bar

and a slope at the drive-wheel end of the table.

And, while double rim wheels are most often found in Scandinavia, they do occasionally show up on wheels that appear to be Scottish, or made by Scottish descendants.

But the man from whom I bought the wheel said that his wife had bought it about 50 years ago in an Acadian area of Cape Breton and was told that it was Acadian.

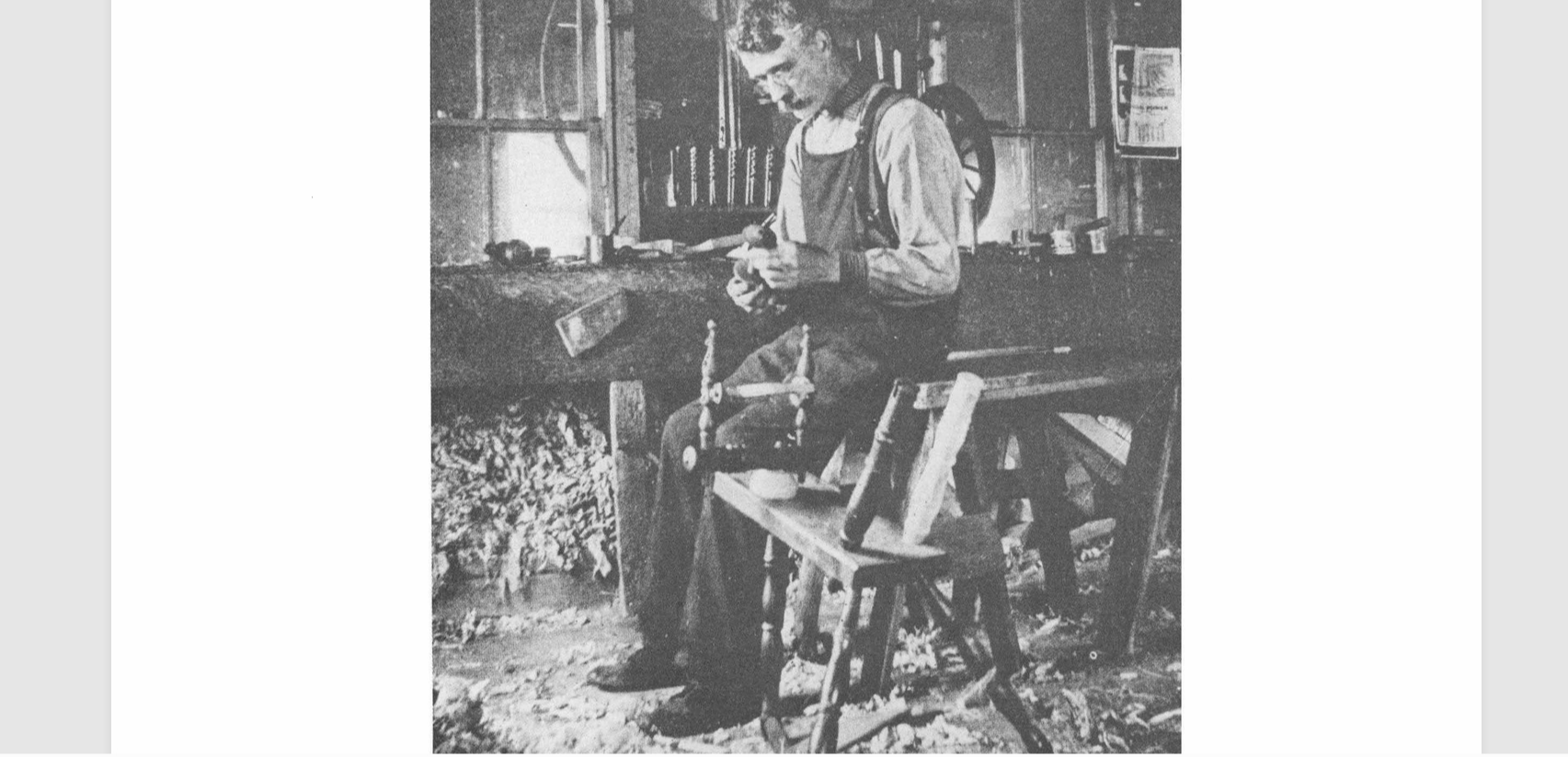

That was intriguing to me because there seems to have been very little research done on Acadian wheels in Nova Scotia, so there is uncertainty as to what wheels were made and used by Acadians there. This photo, found in Judith Buxton-Keenlyside’s book, “Selected Canadian Spinning Wheels in Perspective” (figure 132, p. 278), is captioned “A spinning wheel maker on Ile Madam, Nova Scotia. From

Edith A. Davis, “Cape Breton Island”, reprinted from the Canadian

Geographical Journal 6, no. 3 (1933).”

Ile Madam is the same general area from which the seller’s wife bought Granny Ross. And, the wheel in the photo looks very similar to Granny Ross—especially the maidens,

and the legs.

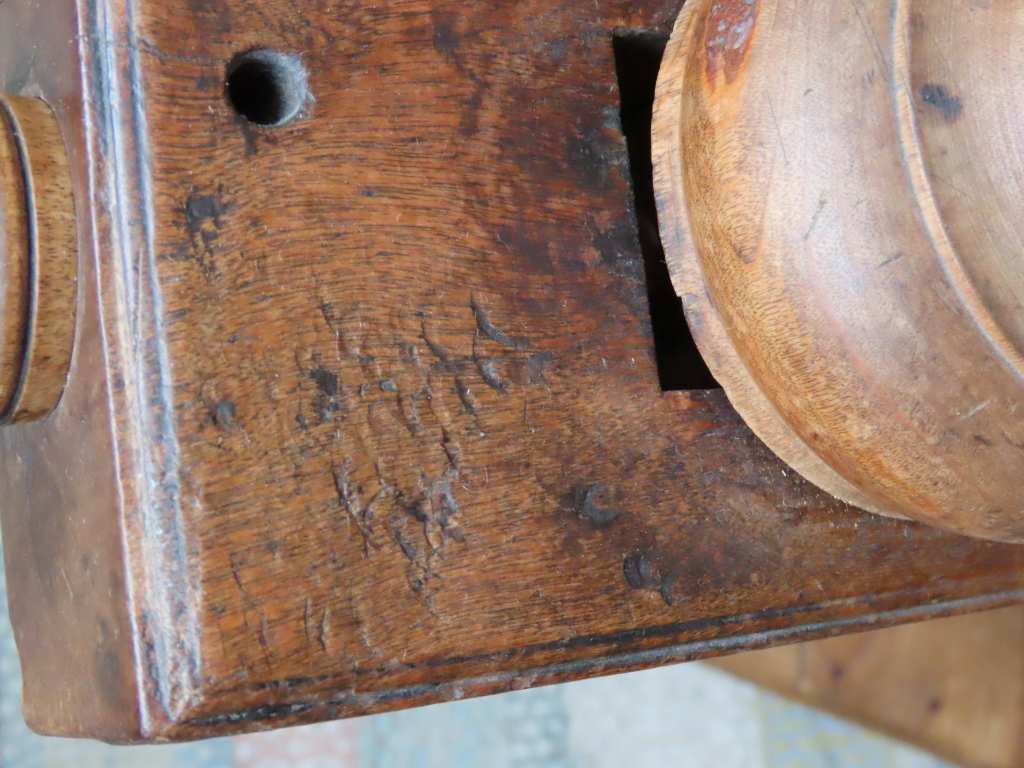

To further complicate things, whoever made the wheel decorated the table with a 6-pointed rosette. While these are sometimes found on eastern European wheels, German fiber tools, and houses and barns of various cultures, I do not believe that I have ever seen one on a Scottish wheel.

Perhaps Granny Ross is a charming composite of different influences on Cape Breton—some Scots, some Acadian, a bit of German.

In any case, she is unique, with her attractive web of spokes,

strong stance,

and beautiful angled upright supports.

The shape of her legs highlights the gorgeous wood grain

and there are small lovely touches, such as the tiered MOA collar.

Much as I love this wheel—and she has been a workhorse for me—I have always felt a pang of guilt that Sherran may have deferred to me on the wheel out of her midwestern politeness.

So, when I decided to sell some of my wheels, I was delighted when we were able to arrange to get Granny Ross to Sherran before Sherran moved farther west (to a place where wheels are rare). Granny Ross now resides with Sherran, where she belongs.