Rosanna was a bonus wheel. I did not want her. I had more than enough large Quebec wheels. I was interested, instead, in the great wheel stored alongside her in a shed. Her owners desperately wanted to clear both out–along with a clock reel–and gave me such a discounted price that ended up taking all three.

I thought I would just clean her up, get her spinning, and find her a new home. I did not expect to become attached. But she was one of those wheels that just clicked with me spinning-wise. She is a powerhouse spinner that loves a fast long draw. So, I kept her quite a bit longer than I expected, just for the great pleasure of spinning on her.

When I first brought her home, she did not look very promising. She had clearly been in the shed for a long time and was dry, spidery, and dirty. I took off the worst of the deeply encrusted grime with turpentine and linseed oil, unstuck her whorl, oiled her up, and away she went.

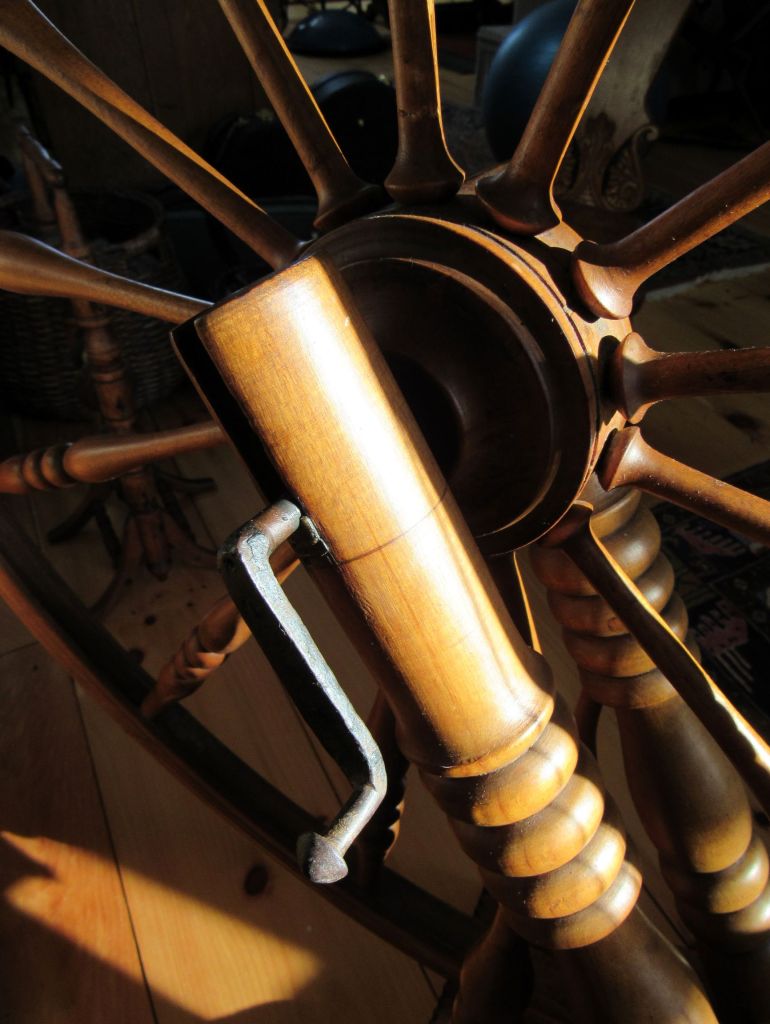

As an aside, everyone who rescues and rehabilitates old wheels should have a rubber strap wrench in their tool box.

They are inexpensive and work miracles on stuck whorls. Just put a knitting needle, skewer, or something similar through the orifice holes to hold onto (rather than the too-readily-breakable flyer arms),

fit the rubber strap around the whorl, and gently twist with the wrench.

Almost all antique whorls are threaded opposite to what we are used to—so turning to the left generally tightens the whorl and turning to right loosens it. The wrench gives great leverage and the rubber strap will not mark or scratch the whorl. No muss, no fuss, no wait.

Being such a wonderful spinner—a true production wheel–it is not surprising that Rosanna shows signs of long use. She was heavily greased around all of her moving parts—now well shrouded in black residue. Her front upright was long ago shimmed with nail.

Her rear upright appears to have been nailed to secure a crack.

Her bobbin is slightly short, giving a bit of chatter. The flyer assembly does not look as worn as I would expect, given the rest of the wheel, so probably is a replacement.

She is one of the few Quebec wheels that I own that fits in the definition of a CPW. She has tilt-tension,

a classic fleur-de-lis metal treadle,

and a large 31-inch drive wheel.

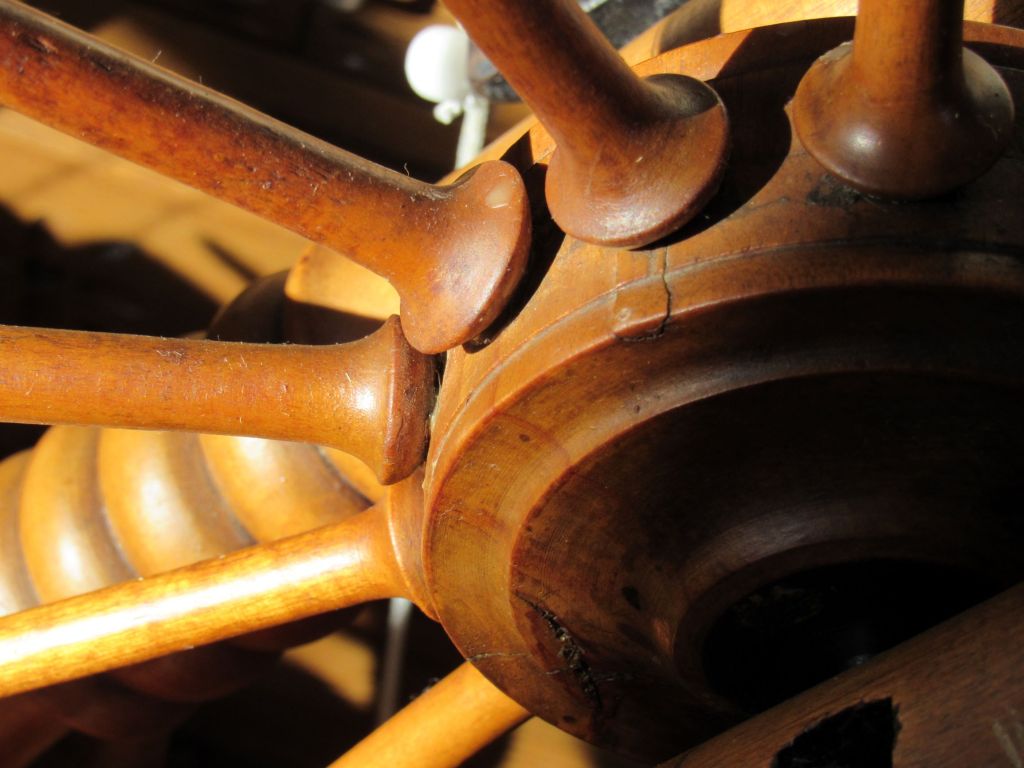

She has no discernible maker’s mark but has features of wheels made by the Laurence family (father Simeon and sons Louis and Clement) near St. Hyacinthe, Quebec. Laurence wheels are characterized by their beautiful beveled and beaded edges,

“s” curve cranks,

secondary upright supports front and back,

pear-shaped feet,

and “flying saucer” maidens.

Some wheels with these same features, however, have been found with a stamp by maker Michel Cadorette. The Laurence and Cadorette families were intertwined with family and wheel-making ties. So, as with so many wheels without a maker’s mark, we cannot know with certainty who made this one—likely a Laurence, but possibly Cadorette. In any case, she is quite a presence.

After spinning on her all winter, I am finally ready to move her on. She is going to a good home, where I hope she will give her new owner many more years of spinning pleasure. Much better than all those years sitting idle in a shed.

For more information on Laurence and Cadorette wheels, see:

Foty, Caroline, Fabricants de Rouets— this book and a photo supplement are available for sale as a downloadable PDF by contacting “Fiddletwist” by message on Ravelry.