This wheel has the feel of a city-made wheel—sophisticated and finely finished. Not surprising, since it was made just outside of Philadelphia. I spotted it on Facebook Marketplace in Connecticut, where it sat for weeks and weeks, with the price lowered from $50 to $25 as the seller appeared desperate to just get rid of it. Although it did not have a spinning head, I had to rescue it—fine Philadelphia great wheels do not come along very often.

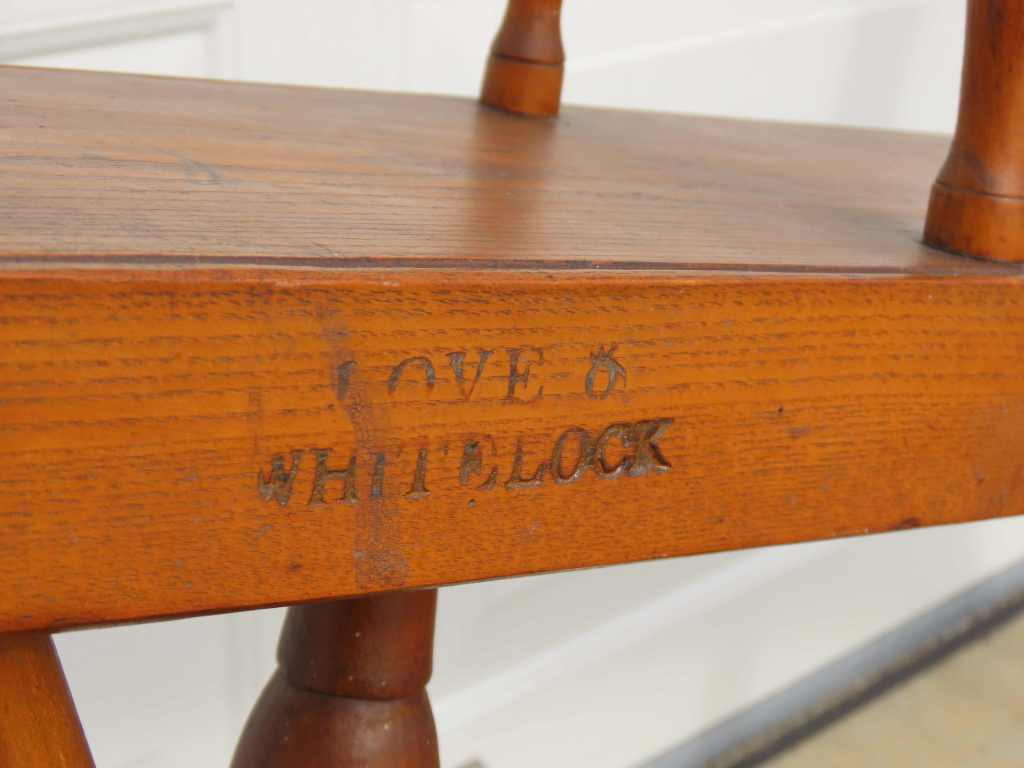

It is a solid heavy wheel, made by Windsor chairmakers, Benjamin Love, and his step-son, Isaac Whitelock.

Love, a Quaker, was born in 1747 in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He married Eleanor McDowell in 1768 and they had ten children over the next two decades, several of whom died young. By 1780, when he was 33, Love was living in Frankford, five miles north of Philadelphia, where he was admitted to the Frankford Preparative Meeting (Society of Friends or Quakers). Their Frankford meetinghouse was built in 1775-76 and now is the oldest surviving Quaker meetinghouse in Philadelphia.

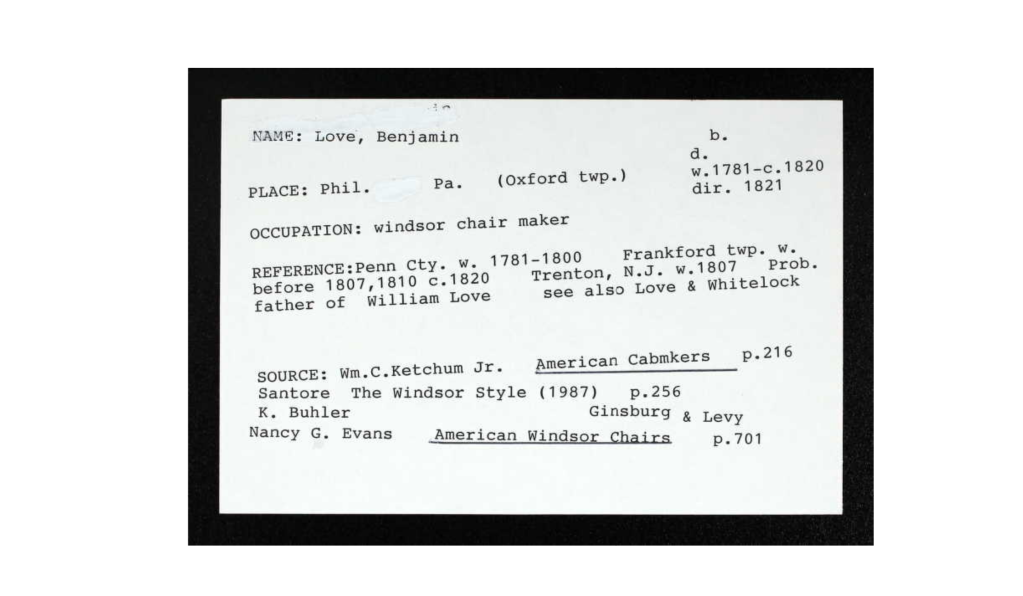

Records show that Love was a Windsor chair maker from 1781 to 1820.

He also took care of and did repair work on the Frankford Meetinghouse, according to the Meeting’s minutes. His wife, Eleanor, died in 1793, and, two years later, in 1795, Love married Elizabeth (Smith) Meharry Whitelock (1752-1829).

Love’s new wife, Elizabeth, had been recently widowed and left with several children, including a son, Isaac Whitelock (1778-1848). In addition to their sizable combined clan of children, the couple took in the daughter of widower, John Davis, who later married Elizabeth’s daughter, Mary Whitelock. In his autobiography, Davis describes Benjamin Love as a “respectable” Quaker Friend. Davis also noted that Isaac Whitelock, Love’s stepson, was in business with Love. (p. 33)

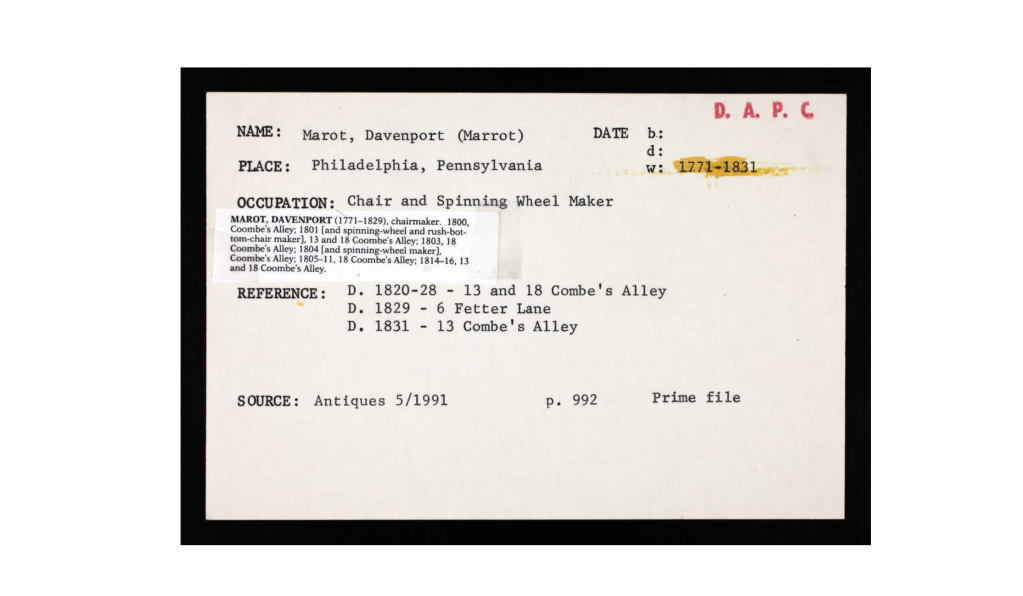

Isaac was about 17 years old when Love married his mother, so a prime age to be trained into Love’s chair and wheel making business. In 1807, when he was 29, Isaac married Ann Woodcock Marot (1785-1865) a Quaker from Delaware. Her uncle Davenport Marot (also spelled “Mariott” and “Marott”) appears also to have been a chair and spinning wheel maker in Philadelphia (from 1771-1829).

Love & Whitelock’s shop was large enough to have an upper loft or attic, called a “cockloft,” where an apprentice may have slept. (Evans, p. 9) By 1818, a few years before Love’s death, it appears that they also expanded into lumber sales, because Love is described as a “Lumber Merchant” in one document. At the time of Love’s death in 1821, Whitelock was described as a “Spinning Wheel & Chairmaker.” At some point later in his life, Isaac Whitelaw gave up chairmaking altogether and focused on dealing in lumber and hardware, running a lumberyard in Frankford from at least 1837 on. (Evans p. 84, fn. 147)

The wheel itself is sturdy and well-made, with a straightforward design of few embellishments or fancy turnings. Its an attractive wheel and I am surprised that there do not seem to be many that have survived. I know of one in the Mercer Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and have seen another one for sale in St. Louis, but compared with some other makers, Love & Whitelock wheels seem to be hard to find.

This one is in excellent condition. The wide drive wheel rim is undamaged, without any cracks or chips. The two-piece rim is neatly joined.

The spokes gently widen as they near the rim, decorated with burn marks midway and near the rim end.

They are firmly attached to the rim with screws.

The hub has intact metal bearings on both sides.

The axle is threaded on the wheel side

and held in place on the other side with folded over metal pieces.

The wheel sits on the axle at an angle, giving more room for the spinner’s arm to turn the wheel.

The table is made of heavy-grained wood,

with grooves down each side, and tall rolag holders.

The barrel tension has a screw for tightening on the non-spinner side.

The wheel came without a spinning head.

I found this direct drive head for it because it is similar to the head on the Love & Whitelock that was for sale years ago in St. Louis. The legs are simple and heavy.

All of the posts extend well below the table and are pegged in place.

The table’s underside included a surprise. The names “Betty Megargee” and “Franklin Lewis” were carefully carved in large squared-off letters, along with the date “1934.”

After some on-line research, I found a Betty Naomi Megargee (1911-1995) who married Benjamin Franklin Graves Lewis (1908-1967) in Philadelphia in 1939. I wonder if this wheel may have been an engagement present. If so, it would have been given in the depths of the depression, which might help explain a five-year engagement.

In the 1930 census, when Betty was 18, she was listed as a Stenographer at a bank and Franklin Lewis as an apprentice electrician. From what I can tell, this Betty and Franklin did not have any children and always lived in Pennsylvania. So, if this wheel belonged to them, I have no clues as to how it ended up in Connecticut. I wish I could confirm that Betty Naomi was the owner of this wheel and that we knew more of her and Franklin’s story.

References:

U.S. Gen Web Archives Philadelphia Wills for a copy of Benjamin Love’s will, witnessed by Isaac Whitelock “Spinning Wheel & Chairmaker.”

Ancestry.com for genealogical research on the Love, Whitelock, Marot, Megargee, and Lewis families, and minutes from the Frankford Preparative Meeting 1772-1794.

Maryland Historical Society, Volume 30, Issue 1, Baltimore, 1935, Autobiography of John Davis.

Evans, Nancy Goyne, Windsor-Chairmaking in America, From Craft Shop to Consumer, University Press of New England, London, NH 2006.

The Pamphlet of the Historical Society of Frankford, Pennsylvania, 1912.