While all spinning wheels are exquisite machines, some bring the exquisite aspect up a notch. This wheel is stunning.

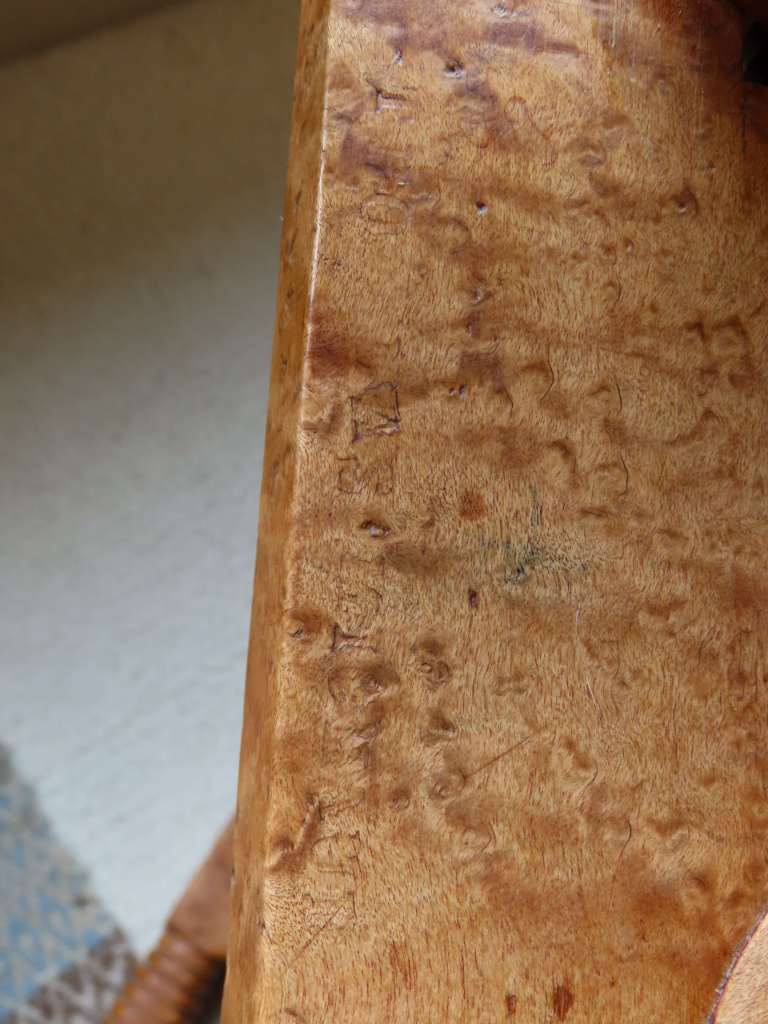

Made almost entirely of birdseye maple, with elaborate turnings and embellishments, it is a showpiece for the skills of its maker, Thomas Michaud.

Unlike many highly decorated wheels, this one also was well-used, coming from the St. John River valley, a region where home spinning continued well into the 20th century.

Where Maine’s upper reaches meet New Brunswick, Canada, the St. John River runs along the border. An area of farmland and timber, it had an interesting mix of settlers in the 1700 and 1800s, with Acadians from the east and Quebecois from the west, joined also by American English, Scots, and Irish.

A book on the ethnic heritage of the region’s furniture is fittingly named “Coalescence of Styles,” but, unfortunately, the book does not mention spinning wheels at all. It is a shame because the area’s wheels are a good example of different influences from Quebec, Scotland, and Acadia.

The Francophone population of the upper St. John River valley (often referred to as Madawaska) was primarily Acadian, but another group of non-Acadian French speakers came from the St. Lawrence River valley in Quebec. The Michauds were among those migrating from Quebec. Thomas Michaud’s father, Prudent, was born in Kamarouska, Quebec in 1815. Those familiar with Quebec wheels may recognize that Kamarouska also was home to the Paradis family of wheelmakers.

While there was intermarriage between the two families (Amable Paradis’ mother was Brigitte Michaud, for example), I was not able to find evidence to show whether any Michauds worked with the Paradis family in making wheels. Nevertheless, the Michaud wheels bear significant similarities to the Paradis wheels, especially in the leg and upright turnings.

Prudent and his wife, Modeste Martin, settled in the upper St. John River valley, specifically in St. Basile, Madawaska, where Thomas was born in 1842. His brothers Ubald (also spelled Ubalde, Hubald, and Hubade) followed in 1844, Joseph Prudent in 1845, and Francois Regis in 1848.

In the 1871 census, Thomas, then 28, is listed as a wheelwright, as is 23-year-old brother, Francois Regis, listed as “Regis.” Brother Ubald, married with children, was listed as a “charron,” or carter in 1871, and as a “wheelwright” by the 1881 census. One wheel likely made by Ubald, signed “Hubade Michaud,” turned up some years ago on Craigslist.

This wheel was discussed on Ravelry and, according to the seller, was from northern Maine and dated 1840. While the photo below shows the maker’s mark, it does not show the supposed date, so perhaps the seller misread a date from 1870, 1880, or 1890 as 1840, since Ubald was not born until 1844. Or, possibly there was another Michaud wheelmaker from an earlier generation, although, as far as I know, no one has found evidence of an earlier Ubald/Hubade.

Despite the poor quality of the “Hubade” wheel photos, the first one does highlight the distinctive maidens, which are characteristic of the upper St. John valley wheels.

We are fortunate to have quite a few photographs of area spinning wheels in use. There is a wonderful paper, “Survival or Adaptation” (tap for link) on domestic textile production in rural Canada in the late 1800s. One area of focus is Madawaska, where spinning and weaving continued to be economically viable as a domestic industry. One of the paper’s writers, Beatrice Craig, also collected information on “Spinning Wheels of the St. John’s River Valley,” which is at the University of Maine, Fort Kent, Acadian Archives.

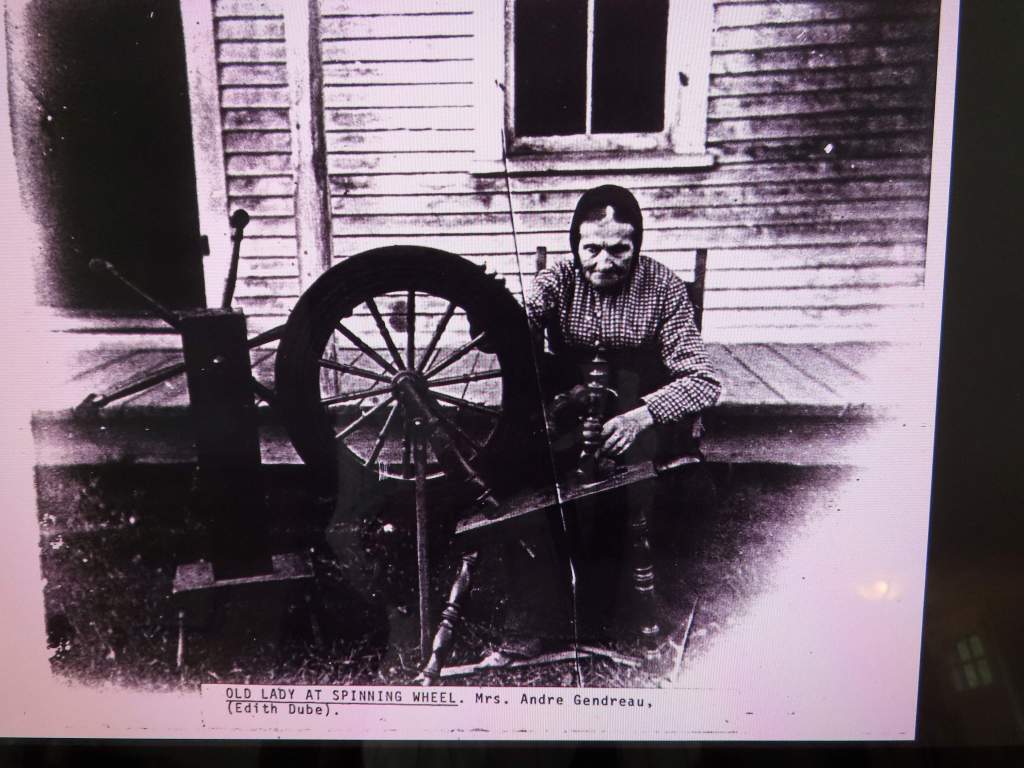

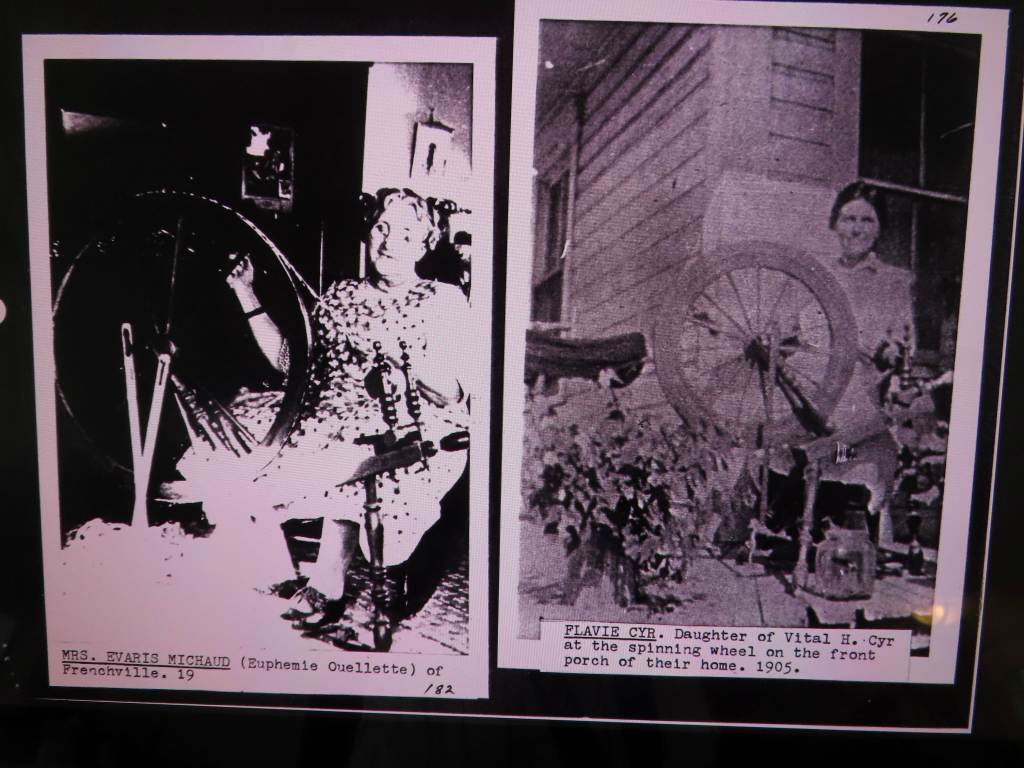

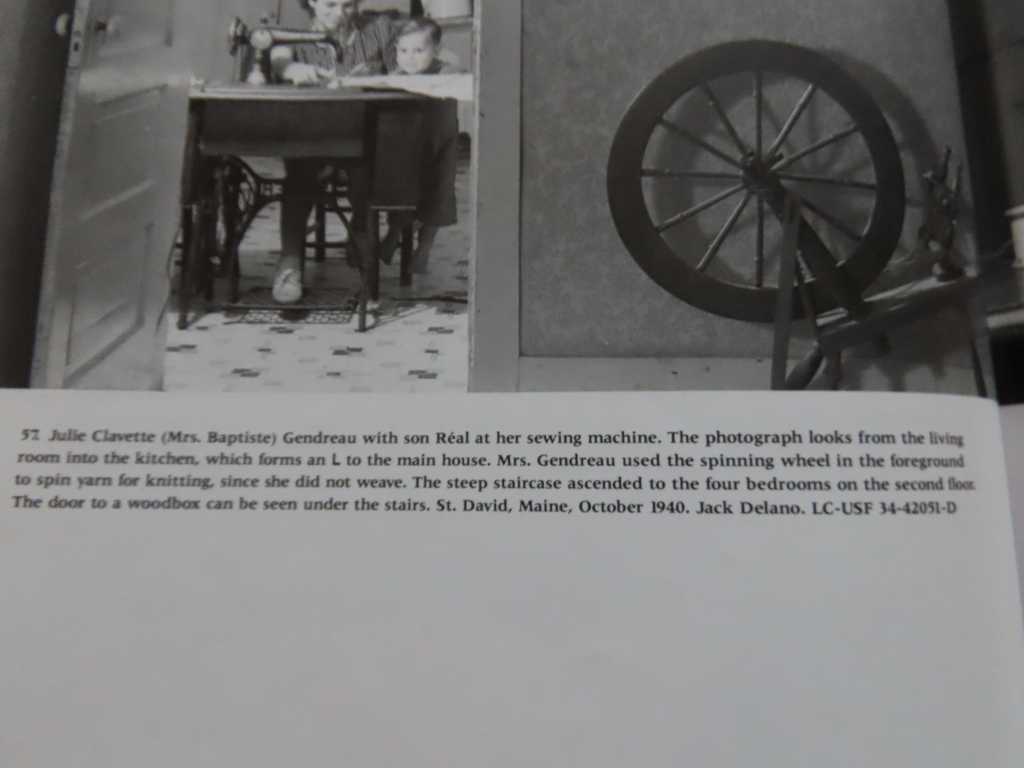

Included in her document are the photos above, from the Madawaska Historical Society’s records, of various wheels from the region. In addition, in the 1940s, the Farm Security Administration sent photographers to the region, whose photos are included in a book “Acadian Hard Times.”

It includes several photos of the hand spinning and weaving that was still going on in the area. While no two wheels in these photographs are the same, many share common features, including, most noticeably, the tiered maidens.

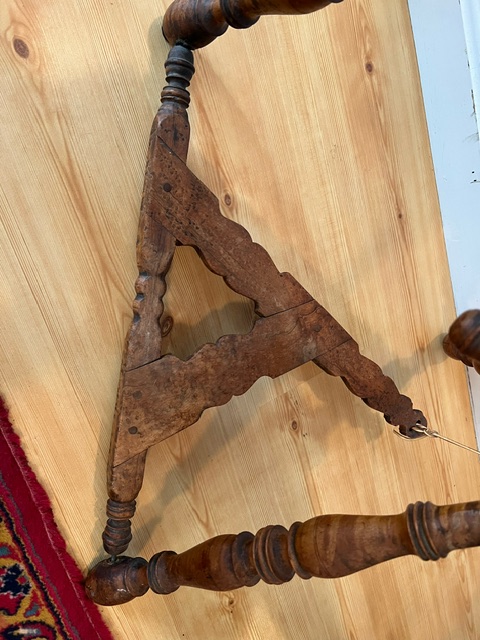

Oddly, my wheel, Philomene, does not have those maidens, but a different style, which showed up on this area wheel.

The photo below shows a wheel with some unique features shared with Philomene.

I do not know whether either of the wheels pictured above were made by Thomas, but clearly, they do not have the elaborate, exuberant details of Philomene. So, I assumed that my wheel was a one-of-a-kind made for some special person or celebration. I was wrong.

Recently I had lunch with some spinning wheel friends and met Diane Howes, a weaver, spinner, and wheel collector from New Hampshire. She is looking to sell some of her wheels and had some questions about them. I was flabbergasted when the first thing she asked about was a wheel marked “T. Michaud,” because I was not aware of any other wheels with his mark.

When she said it was a really fancy wheel with beautiful wood, I about jumped out of my chair with excitement.

Diane’s wheel, which she got from collector Sue Burns (Diane says it was one of Sue’s two favorite wheels), is a sister to mine, except for the maidens.

Unsurprisingly, the maidens on her wheel are in the classic style of the valley. As with Philomene, Diane’s wheel is made primarily with birdseye maple.

This rare wood is found in the area and has long been valued for furniture-making there.

Very occasionally antique wheels have some small parts made of birds-eye maple, but these two wheels are the only ones I have come across made almost entirely from this heavy, hard, durable, but oh-so-lovely wood.

Diane’s wheel has some even fancier turnings than mine.

And hers has no hole in the table.

These close-to-the spinner holes—not in the place typical for distaffs–have long been a subject of discussion, with theories that they likely were for a distaff or a water bowl.

Most Quebec wheels do not have them, with the exception of the family of mystery giantess wheels discussed in the blog post “Olympe.” They have been found in wheels associated with the Acadians, however, where a bowl, called a “godet,” could be inserted.

It has usually been assumed that the bowls were used for water for flax spinning, but they seem also to show up on wheels that likely were used for spinning wool. This photo I recently ran across of a woman spinning wool with a bowl sitting on the wheel’s table seems to suggest that the bowls might also have been used for grease or oil for wool spinning.

Here are a couple of examples of “spinning wheel bowls” found in the Canadian Museum of History’s online collection.

I do not know if Philomene spun flax, wool, or both, but the treadle, even though made of very hard maple, is smoothly worn down from years of use and one flyer arm has an old repair.

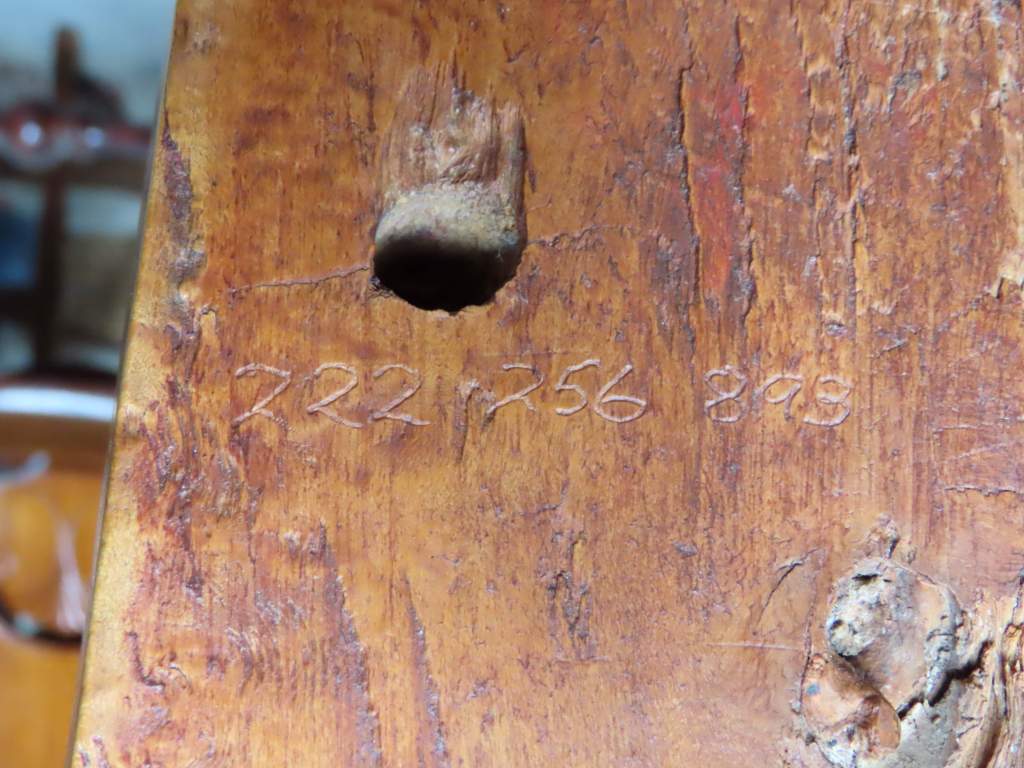

At some point, Philomene must have been in a museum, because there is an accession number carved in two places on her underside.

Little did I know when I first saw a photo of this wheel up for auction that it would open up a whole fascinating world learning about the Upper St. John River Valley and its spinning and weaving tradition.

The wheel itself has turnings similar to Quebec Paradis wheels,

hints of Scottish influence in the stance, size, and spokes,

a possible Acadian touch with a place for a water dish, and several unique features of its own, such as the treadle and angled table sides.

The combination makes for a wheel that is distinctive to the Upper St. John River Valley and its people. As for Thomas Michaud, aside from census records, I was not able to find any information about him.

He does not appear to have married and I could not find a record of his death. Fortunately, he left us some remarkable wheels.

Thanks to Diane Howes for the photos of her Michaud wheel, to Carolyn Foty and the people on Ravelry for the research and photos of the Hubade Michaud wheel, to Patrick Lacroix, Director of Acadian Archives at the University of Maine in Fort Kent, and to Gordon Moat for his kindness (as always) in picking up this wheel and getting it to me.

References:

Craig, Béatrice, Spinning wheels in the Valley documentation (15.13.7), Ready Reference files, Acadian Archives/Archives acadiennes, Fort Kent, Maine

Craig, Béatrice, Rygiel, Judith and Turcotte, Elizabeth, Survival or adaptation? Domestic rural textile

production in eastern Canada in the later nineteenth century*

Acadian Culture in Maine, North Atlantic Region, National Park Service, 1992

Cook, Jane L., Coalescence of Styles, The ethnic Heritage of St John River Valley Regional Furniture, 1763-1851, McGill-Queen’s Univ. Press, Montreal, 2001

Doty, C. Stewart, 1991 Acadian Hard Times: The Farm Security Administration

in Maine’s St. John Valley 1940-1943. Orono, Me.: University of Maine Press, 1991