This wheel is a lovely marriage (perhaps polygamous) of wheel parts—also known as a Frankenwheel. I prefer to think of it as a mélange or medley wheel, a hodgepodge of parts by different makers working together in harmony.

By the time they get to us, many Quebec wheels have replacement flyers or drive wheels. Even when parts were from different makers, there seems to be a happy interchangeability. Zotique is an interesting mix, with some unusual features. A Quebec wheel, with a drive wheel diameter of about 30 inches and a tilt tension system, it falls within the definition of a Canadian Production Wheel (CPW).

As with the wheel in the previous post, Zinnia Rue, the body of this wheel was almost certainly made by a Vezina. While Zinnia Rue likely was made by Ferdinand Vezina, this wheel appears to have been made by Ferdinand’s son, Antoine Emile, or Ferdinand’s younger half-brother, Charles.

Both Antoine Emile and Charles made wheels with distinctive double metal-slat treadles and a tension system cradling the MOA in a block of wood held in place with an iron U-bolt.

While I cannot be sure which Vezina made this wheel, I am inclined to think it is Antoine Emile for two reasons. First, he apparently marked his wheels with a paper label on the table, whereas Charles marked his with a stencil. I cannot find any trace of a stenciled mark on this wheel, but there are marks on the table that look as if a paper label, or remnants of a label, were scraped off at some point.

In addition, Antoine Emile’s wheels often had metal flyer bearings—he apparently was inclined to experiment. While this wheel does not have metal flyer bearings, it has something even more unusual—wooden bearings.

I have only heard of these on a handful of wheels, so they likely were experiments.

The bearings are screwed into the maidens.

The rear bearing has a hole in the top and there has been some speculation that it may have been designed for oiling the bearing.

On this wheel, however, the hole does not go through to the opening for the flyer shaft, so, unless it is really gunked up, that theory is out the window.

The wheel has only one secondary upright support, on the non-spinner side. The table is slightly tapered and has a hole going all the way through.

These holes are found on some Quebec wheels, but most do not have them. The obvious use for the hole would be for mounting a distaff or a water dish for spinning flax. Although flax was grown and spun in Quebec, it was not widespread, especially by the time that this wheel was manufactured in the early 1900s (Antoine Emile patented this wheel style in 1899). In fact, these wheels were designed and singularly suited for spinning wool, fine and fast–not flax. Moreover, I am not aware of any photographs showing flax spinning or distaffs on a tilt tension Quebec wheel. So, the hole remains a bit puzzling.

At some point, the original flyer was lost and replaced with this mustard-yellow painted flyer, which likely came from an Ouellet or Paradis wheel.

It has a smooth bell-shaped orifice and has spun many miles.

There is a deep groove where the thread ran from the orifice to the hooks and a series of grooves on the edge of the flyer arms.

While grooves running from the orifice are common and easily explained, many Quebec flyers do not have grooves on the arm.

You see them a lot on New England and Nova Scotia wheels, but less often on Quebec wheels. The origin of these grooves is a source of debate. The two most prevalent theories are that they are the result of cross-lacing or winding off. In cross-lacing, yarn is passed from hooks on one side of the flyer to the other, which helps control the speed of the uptake, allows for more uniformity of finely spun yarn, and—with linen—helps to even out the ridges that are formed on the bobbin as the thread piles up at the point of each hook.

I am no expert on cross-lacing—I do not use it at all. And I do not know how common it was for Quebec production spinners. But on almost all of my flyers with arm grooves, the grooves seem to be on the wrong edge to have been made by cross-lacing, as I understand it. If I have this wrong, I hope someone will correct me.

On the other hand, the grooves are on the edge that would have been impacted by winding off. Most antique wheels did not have multiple bobbins and thread was wound off onto a reel when the bobbin was full. In winding off, many spinners ran the thread around the tension screw handle on the way to the reel. With most wheels, an arm comes to rest against the thread as it heads to the tension screw.

The thread usually rubs against the inside of the flyer arm at a pretty good rate of speed, moving along the length of the bobbin as it winds off.

I suspect this is what caused the grooves, but without more evidence, it is just speculation.

Still, it is interesting that when Quebec wheels evolved to tilt tension, the tension knobs remained, perhaps not only as a handle for carrying, but as a tool for winding off. I have several Nova Scotia wheels where heavy flyer arm grooves are matched by heavy grooves in the tension knob. This wheel does not have grooves on the tension knob, but I would love to see if there are grooves in the tension knob on this flyer’s original wheel.

This wheel’s graceful, outsized drive wheel also is a bit of a mystery.

In general on Quebec wheels, spokes are a defining feature for different makers. But this wheel’s relatively plain spokes do not seem to be associated with any particular maker.

They are not very common, but turn up here and there on various makers’ wheels, sometimes with an unusually large number of spokes–16 or 18 compared with the more typical 12 or 14. This one has 18 spokes—quite beautiful and rarely seen.

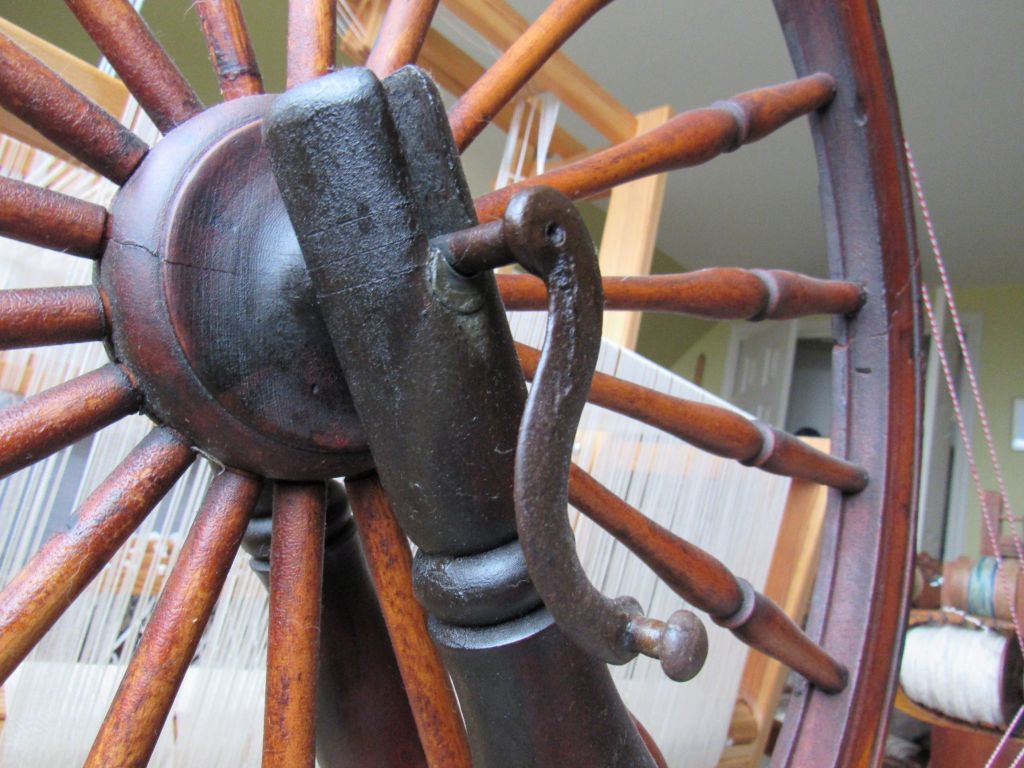

The axle crank is “S” shaped, which is less common than “C” shaped cranks, and often associated with Laurence wheels.

I have wondered if these drive wheels might have been manufactured by Laurence (or someone else) to be available as replacements. The simple spokes would not clash with different maker’s wheel styles and having 16 or 18 spokes and an S crank might have been seen as a lovely upgrade feature.

But, that is purely speculation. Oddly enough, both of my Vezina wheels have this style spoke (but with different crank styles), and the drive wheels appear to match the rest of the wheel’s wood and finish, so perhaps they were occasionally offered by the Vezinas.

As with many mélange/Franken wheels, this one is a wonderful spinner.

I enjoy this style of metal treadle—it has some give to it, making it very responsive and easy on the foot.

The wheel is beat up, with some chips,

especially along the drive wheel rim.

But, with its size, 18 spokes, wooden flyer bearings, and yellow flyer, it stands out as a unique and striking survivor.

January 25, 2021 update: In pondering whether this style drive wheel may have been sold as a replacement wheel, I found this advertisement for spinning wheels sold by Dupuis Freres, a major Montreal department store that sold wheels as late as 1948 (mostly made by Borduas). The advertisement offers drive wheels only, or “Roue seule,” so this establishes that replacement wheels were sold as separate items.

For much more information on Antoine Emile and Charles Vezina see Caroline Foty’s book and photo supplement:

Foty, Caroline, Fabricants de Rouets— this book is available for sale as a downloadable PDF by contacting “Fiddletwist” by message on Ravelry.: