Early Quebec wheels probably had little resemblance to the large, metal-clad production wheels associated with Quebec today. It is likely that many were flat rim wheels, which are still found in Quebec, Ontario, and New England.

The origin of these flat rim wheels is a bit of a mystery. Some likely came from the Acadian settlements in Canada, but it is doubtful that they are all Acadian. Many Quebec settlers came from the northwest of France, and, interestingly, these wheels resemble the flat rim wheels of Normandy.

Whatever their origin, Quebec flat-rim wheels are thought to date from the late 18th century into the early 19th century. They come in various forms. Some have treadles, some are hand-cranked.

Tables may be flat or sloped, often with four legs, but sometimes three. Their profile is distinctive—a long, wide, sturdy table, shortish legs, with an outsized drive wheel and flyer set-up.

In fact, some wheels of this style are not flat-rimmed but have drive wheels like those on saxony-style wheels, looking almost apologetically out-of-place atop the squat wheel bodies.

The flyers and tension systems on these wheels set them apart from other antique wheels.

Most are not double drive, but have some form of “scotch” tension, with a single drive band for the whorl and a brake on the bobbin, usually adjusted with a small knob inserted in a hole in a bar over the flyer assembly.

My wheel is unusual because, aside from the flyer assembly, it has no turned parts.

Aside from the hub, nothing is round.

The spokes, legs, uprights, and upright supports are all straight-sided with chamfered edges.

The spokes are particularly nice, six-sided and tapered.

Old nail holes indicate that the rim was re-positioned at some point.

The table is sturdy and flat.

The lines of the wheel—all edges and tapers—are very beautiful and quite unique.

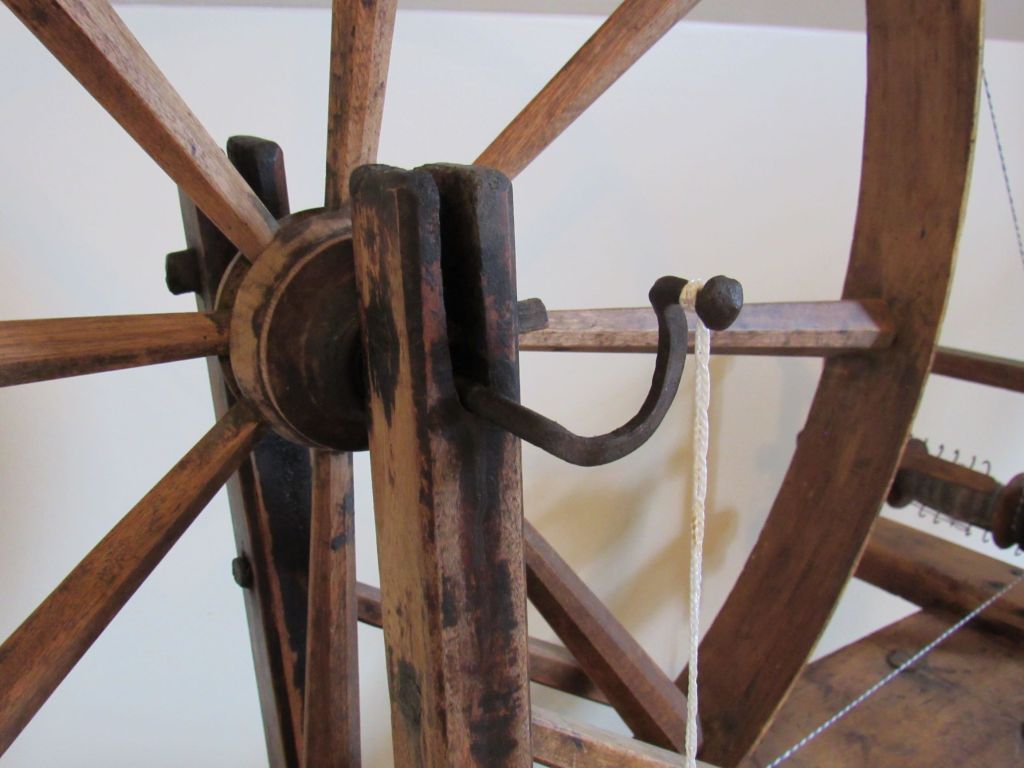

The flyer is large, held in place with a small removable piece on one end.

As with many of these flat-rim wheels, rather than having a removable whorl and fixed arms,

the whorl is fixed on the shaft, while the arms and bobbin can be removed.

The shaft is a smooth cylinder with a single cut-out for the yarn to emerge onto the arms.

This style orifice often is referred to as a whistle-cut or train-whistle because it looks like the half-circle cut out on steam engine whistles.

A single drive band rounds the whorl, while another band is attached to a nail on the end of the table, rounds the bobbin, with the other end held in place by a peg in the crossbar above the flyer.

There are grooves at each end for the band to ride in.

When the band is inserted in a hole through the peg, it can be tightened by turning the peg, which adjusts the amount of drag on the bobbin.

Once the tension is adjusted to its sweet spot, my wheel spins beautifully, although the treadling takes a little more effort than with most wheels. The treadle is supported only by the wooden back bar.

And, in contrast with most treadled wheels, that back bar does not have metal rods on each end to serve as the turning pivots in the legs. Instead, the wooden ends of the bar extend into the legs.

The wood-on-wood action in treadling creates a little more resistance than I am used to, so I usually use two feet which works well with the sturdiness of this wheel.

These wheels look a lot like bobbin winders and many were converted to that use. So, it is always a treat when one turns up with all its spinning parts.

Especially when it bears the hand of an artist who was not willing to settle for utility alone, and, without a lathe, created something that pleases the eyes as well as the hands.

For more information on flat-rim wheels, see:

Burnham, Harold and Dorothy, Keep Me Warm One Night, Early Handweaving in Eastern Canada, University of Toronto Press, 1972, p. 34.

Buxton-Keenlyside, Judith, Selected Canadian Spinning Wheels in Perspective: An Analytical Approach, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa, 1990, pp. 206-09.

Cummer, Joan, A Book of Spinning Wheels, Peter E. Randall, Portsmouth, N.H. 1984, pp. 178-79.

Foty, Caroline, “Flat-Rim Spinning Wheels,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue #80 (April 2013).

That’s a fascinating wheel, and a lovely detailed set of photos! Those wooden ends to the treadle bar, which fit into holes in the legs – what (if anything) do you lubricate them with? I use candle wax on wooden tension screws, but that might be difficult with these.

LikeLike

I’ve tried getting some candle wax in there, but there just isn’t any room to apply it. So, the short answer is that I haven’t been lubricating them. I’d welcome any other suggestions!

LikeLike