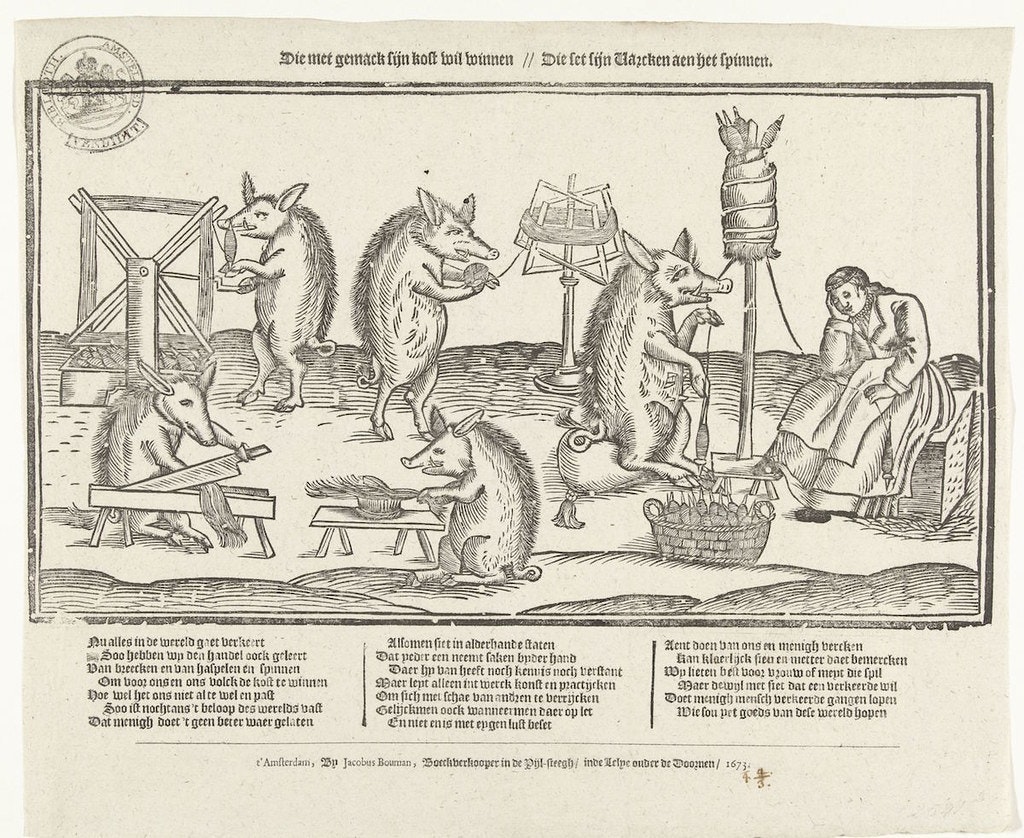

Hackling is the final step in processing flax for spinning into linen.

Processing requires many steps. At about ninety days from planting, flax plants are pulled and dried. The seeds are removed by rippling, the woody portions broken down through retting and crushed by breaking,

and separated from the fiber by scutching (to learn much more about these processes, see the previous posts “A Ripple and Breaks” and “Scutching Knives”).

Finally, to further refine, soften, and clean the fiber, it is combed through hackles, also known as heckles, hatchels, and hetchels.

Hackling separates coarser, shorter fiber, called “tow,” from the longer line fibers, which are the most desirable for spinning.

Hackling also removes the small woody bits of boon or shive still clinging to the fiber, and splits ribbony pieces into finer filaments.

Hackles come in as great a variety as the people who made them. All sport sharp–often very sharp–tines. But tines are of different sizes, shapes, lengths, and densities.

Ideally, several hackles are used, starting with large tines, spread far apart for the initial combing, and progressing to a medium density comb and then one with smaller, finer, more closely-spaced tines.

But, it is possible to get good results with one medium hackle, which likely often was all that was available.

I am fortunate because hackles are very easy to find in Maine. They turn up regularly at antique stores and barn sales. I have been able to pass on many hackles to others interested in processing their own flax and still have every gradation available for processing my own.

The three hackles above are a coarse grade and the ones I use for the first combing passes to remove the roughest tow and boon. The largest has huge angled tines and a handle.

It would make a formidable weapon.

Most hackles in this country were designed to be secured to a table or plank for use. But this one is unusual, being free-standing, which makes it easy to move around and to use while sitting. This one is my favorite for the first comb.

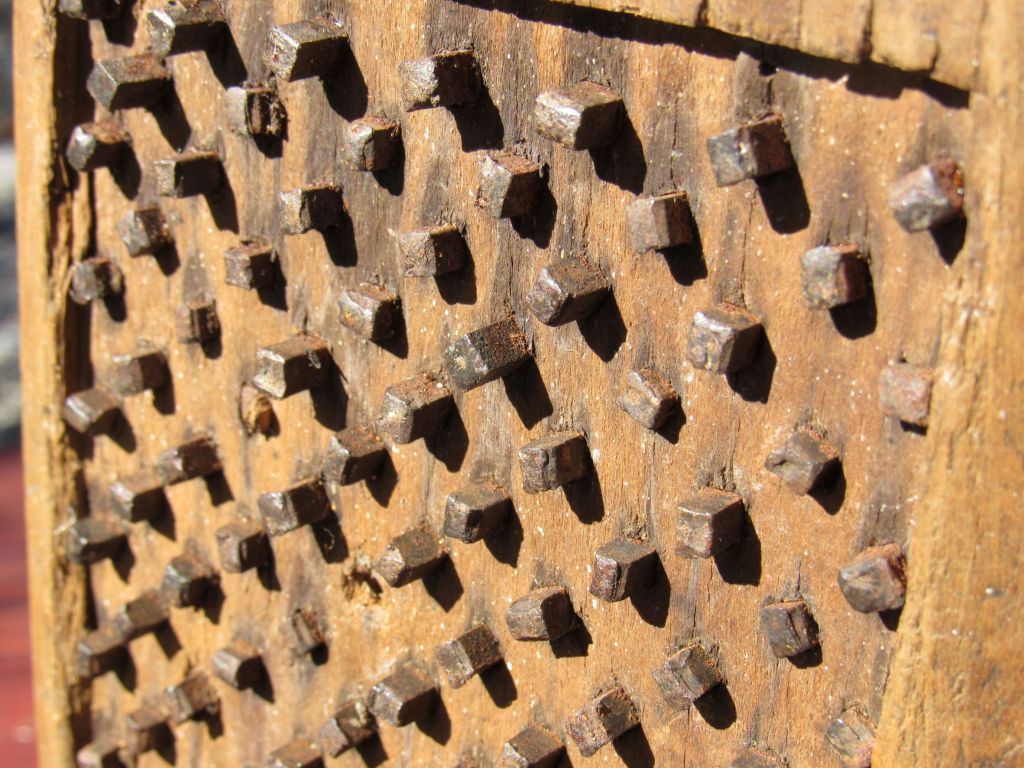

Typically, nails for tines were heated and driven through green wood, which would secure them tightly after drying. It’s always interesting to examine the backside of hackles. I know very little about nails, unfortunately, so am unable to translate nail types into any useful information about when or where specific hackles were made.

Some tines are square, others rounded. I have not been able to determine any real pattern for the difference. Hackles from New England seem to come in both varieties.

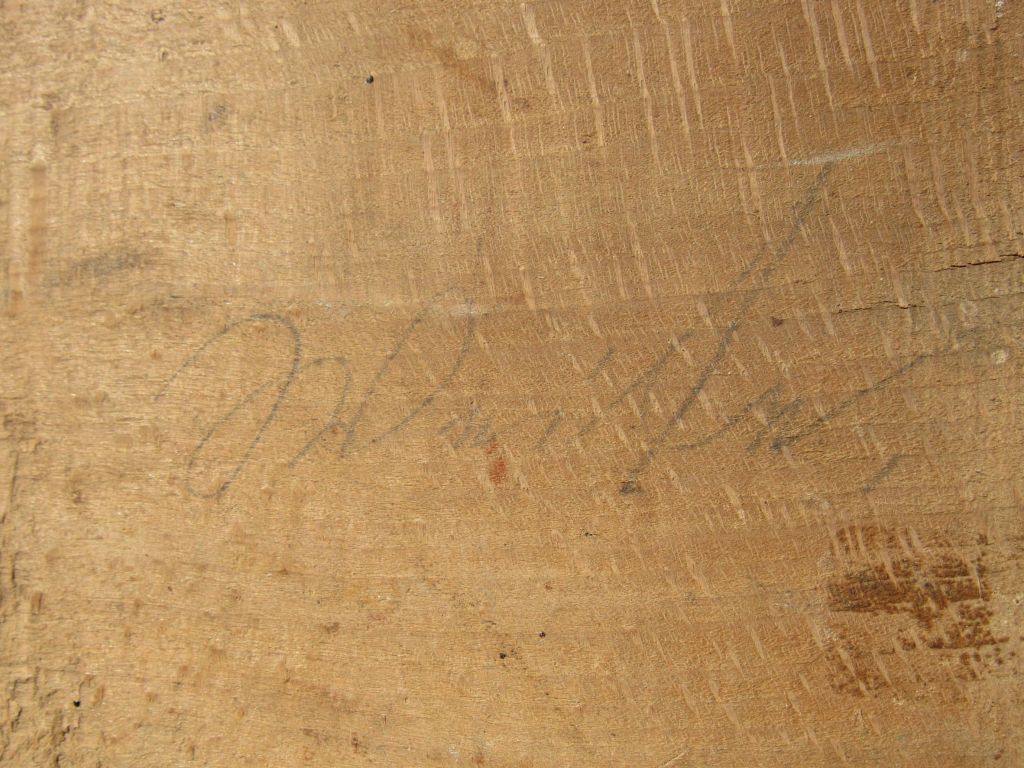

This lovely set of hackles is made of tiger maple,

is initialed,

and has a cover.

It is a coarse to medium size, with round tines.

This is a nice medium set, with a sheet of metal where the tines emerge, apparently used to help keep the wood from cracking.

On the underside is a faint incision of “Hackle 10.00,” indicating that “hackle” probably has been the term used in this area for some time. I found it at Maine antique mall and, when I went to check out, the man behind the counter asked if I had seen the other set with a cover. I hadn’t and what a treasure it turned out to be.

One side has the name “John Pain Darlington.”

On the other side, is the name “Thomas Paine Darlington.” Darlington is an old Maine name, but I have not yet pinned these two down. Given the “Thomas Paine,” I’m hoping this dates from the 1700s. (See Update below for more information.)

The back side is amazing. And when the cover was lifted, the longest, sharpest tines I have ever seen were revealed.

The cover inside is scarred from the tines, as are all the hackle covers that I have seen.

There was old flax on it when I bought it, complete with pieces of boon.

Most of the New England hackles I have seen have tines in a square or rectangular pattern. The one below one has a circle of tines, something more often seen in European and Scandinavian hackles.

It is on a thick plank of coarsely-grained wood, perhaps chestnut, with amazing scribe lines marking tine placement.

The blank holes probably were pre-drilled and then left empty, as shown by the darkened area on the underside, perhaps a result of heated nails.

The next two hackles are European, probably Scandinavian.

This style hackle was used while seated, held at an angle between the legs, anchored with a foot or board at the lower opening.

This style, with nails emerging through a separate wooden disc secured by a metal band, does not seem to hold the tines as securely as those where the nails are driven through the body of the hackle itself. As a result, the tines become skewed with use.

The tine disc is held to the body with nails bent over in the back.

This beauty is initialed and dated. I like to think that the decorative carved plants are flax.

I believe the next set of hackles is eastern European.

It is very long and narrow.

The raised area for the tine disc is hand carved.

Occasionally painted hackles turn up. These two came to me from Pennsylvania but I do not know if they were made there.

I have seen this particular paint design on several identical hackles for sale in Pennsylvania.

This one is dated 1899 and has the same tine design as the Scandinavian hackles.

It is in excellent condition.

It is decorated with little indentation carvings along with the painting.

There is penciled writing on the back that I cannot decipher.

I have three sets of fine hackles. They are much harder to find than the mediums.

This one has beautiful reddish wood for the cover.

The wooden ends are covered with metal plates, giving a more durable and steady surface for securing the smaller hackle to a table.

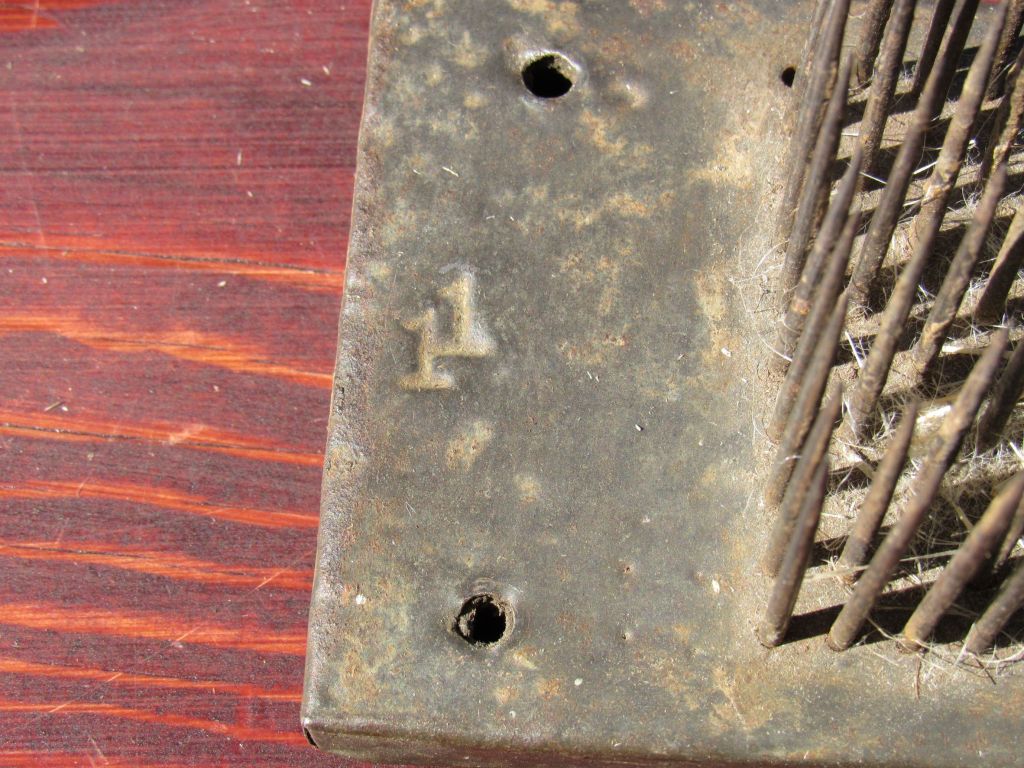

The next set is quite small and fine, with the whole hackle body covered in metal. I have seen three sets like this one in New England, all identified as hackles.

They all had a number stamped in the end, likely a grade of tine size.

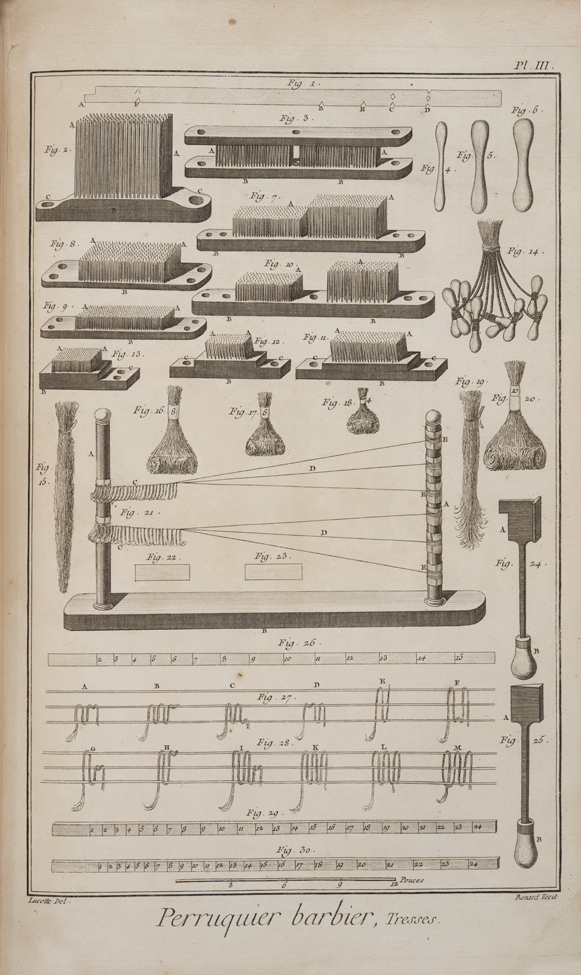

Recently, someone posted in a Facebook flax group an advertisement for modern wigmaking hackles. They looked a lot like this one. Diderot’s Encyclopedia of manufacturing in 18th century France, included this illustration of wigmaking tools. So perhaps these very small hackles were used for wigmaking rather than flax processing. Or maybe not.

The finer the hackle, the finer and cleaner the flax for spinning. This is the finest hackle I have ever seen.

It’s a gorgeous tool.

Extremely fine, closely set tines were bound in brass.

After hackling, in some parts of the world, the final step is brushing. As far as I know, this was not a practice used in New England but a finishing touch given to fine flax in parts of Sweden, Finland, and Belgium.

Using it on nicely hackled flax is a bit like brushing a horse’s tail.

November 19, 2021 Update: In the middle of the night after posting this, I realized I had not recently read over the articles on hackles in The Spinning Wheel Sleuth. A bad oversight. This morning, I found a clue to the “Darlington” hackle in an article by Carlton Stickney, who has an absolutely amazing collection of hackles. One of the hackles featured in Carlton’s article was marked “Ridsdale Porter Darlington.” The lettering on the hackle side matches the lettering on my hackle marked with “John Pain Darlington” and “Thomas Pain(e) Darlington.” Carlton’s research found that Ridsdale and Porter were “forgers, makers and grinders of Heckle-pins in Darlington for several years.” (p. 9) Darlington is in Durham, England.

I immediately started researching John and Thomas Pain and found reference to “Catherine Pain” listed as a Hecklemaker in Durham, in the Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce & Manufacture (post 1791, pre 1800). In the Durham Probate Records (1776-1799), I found reference to both “Catherine Pain & Co.” and “John Pain” as hecklemakers in Darlington. I have not yet found the exact probate dates or a relationship between John and Catherine. Nor have I found a relationship between the Pains and Ridsdale or Porter. Because the printing of the word “Darlington” on the hackles looks so similar, however, it would seem there was some relationship there.

No wonder I could not find Thomas and John Darlington in my Maine research. I was barking up the wrong tree. I will continue the research and post updates.

See: Stickney, Carlton, “Flax Tools,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth #96 (April 2017).

For more information on flax processing and hackles:

Henzie, Suzie, “Three Hackles,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth #54, (October 2006).

Burnham, Harold B. and Dorothy K., ‘Keep me warm one night,’ Early handweaving in eastern Canada, Univ. of Toronto Press, Toronto and Buffalo, 1972.

Dewilde, Bert, Flax in Flanders Throughout the Centuries, Lannoo, Tielt, Belgium, 1987.

Heinrich, Linda, Linen From Flax Seed to Woven Cloth, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 1992.

Meek, Katie Reeder, Reflections From a Flaxen Past, Pennannular Press Int’l, Alpena, Mich., 2000.

Merrimack Valley Textile Museum, All Sorts of Good and Sufficient Cloth, Linen-Making in New England 1640-1860, Merrimack Valley Text. Mus., North Andover, Massachusetts, 1980.

Zinzendorf, Christian and Johannes, The Big Book of Flax, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 2011.

For more information on flax brushes see Josefin Waltin’s blog “For the Love of Spinning.” https://waltin.se/josefinwaltinspinner/flax-brush/

Well I thought wasn’t interested in flax processing, but that is fascinating!

LikeLike

Ha. I love flax and everything about it. It’s amazing to me to see the similarities and differences in flax processing tools from different regions. Such hard work, but such an amazing fiber.

LikeLike

What a wonderful and amazing history presentation about the tools for processing flax! It was like have a truly personal visit to a museum. So this is why there wasn’t time to sit and be idle, not if you wanted clothing on your back. Thank you!

LikeLike

That makes me feel wonderful. My hope for this blog is that it will be a bit like an on-line museum. The amount of work required to process flax is kind of mind-boggling. No time for TV!

LikeLike

What a wonderful post, Brenda! I’ve never seen so many hatchets. So satisfying. Books never show enough. On one of my Ravelry groups it was hypothesized that the square hatchel tines may have helped remove leftover bits of boon in a way round times would not. Likely, also, was the blacksmith who made the tines preferred either square or round. Which was easier to make? Blacksmiths, out there?

Do you have a favorite hatchel?

LikeLike

Thanks Susanne! I have heard the speculation about square tines, too, but can’t say that I’ve noticed any difference in the ability to remove boon. I always assumed it had more to do with what was available and that the rounds tines were more difficult to make–but I really am ignorant about this topic and would love input from people with more knowledge.

I don’t have a favorite, but if I could only keep one, it would be the tiger maple with the initials and cover. It was the first one I bought, first one I used, and a beautiful tool.

LikeLike