This beautiful wheel is Finnish. In fact, even though there is no maker’s mark, I know with certainty who made it. That is a rarity in the wheel world. I found it for sale on Cape Cod. Despite the fact that it had been in the seller’s home all his life, he knew nothing about its history.

Because the wheel looked Scandinavian, I asked him about his family background. Sure enough, they are Scandinavian, mostly Norwegian, he thought. When I got the wheel home, I realized that it was in pristine condition—probably never used for spinning.

In addition, it looked relatively new compared to my other wheels, most of which were made in the 1800s. It seemed likely that the wheel was made in the 1900s, which made we wonder if it was Finnish, because Finland, like Quebec, had significant spinning wheel production in the early to mid-1900s.

Fortunately, there is a Finnish wheel collector on Facebook, Sauli Rajala, with a page called “Rukkitaivas ‘Spinning Wheel Heaven’ Kiikka,” in which he photographs wheels that he collects in and around the Kiikka region of Finland. As of March 2022, he has rescued more than 1600 wheels. They are so abundant in his area, which was once a thriving center of wheel making, that they are often given away. One day I saw a wheel on his page that looked just like mine.

He knew the area in which he had found it, but no other details. A few months later, another similar wheel showed up, but no one seemed to know anything definitive about where the wheels were made. Of course, I may have missed huge chunks of information since I speak no Finnish and Facebook translations range from hilarious to vaguely obscene. I’ve come to understand some of the wonky translations, such as “Rukki,” the Finnish word for spinning wheel, which translates as “rye” and “lantern” is the translation for flyers.

Translated posts usually go something like these: “The roller has to spin an obstacle with a krake and a lantern in the leather earrings,” and “the between the thighs must not be at all tight so that bike is not an obstacle.” Translations are littered with “bitches,” “wheelbarrows,” and “the Polish side.” Let’s just say that the translation feature is usually more laugh-inducing than illuminating. So, although I was fairly confident this wheel was Finnish, that was the extent of my knowledge.

Until recently, when someone posted in the Rukkitaivis Facebook group a wheel similar–but slightly different–than mine, with the information that her aunt said it had come from central Finland. I posted a photo of my wheel asking if she thought it would have come from the same region. In response, I was amazed to hear from Marja Tolonen, who said that my wheel had been made by her grandfather, Hannes Rantila, who shipped a batch of wheels to America for sale in 1922.

Marja’s father, Edvard, grandfather, Hannes, and great-grandfather, Sakari Rantila, all made spinning wheels in Manniskylä, Keuruu. Sakari started making wheels in 1845. He could read and write and kept a record of all the wheels and other turnings he sold.

Sakari’s son, who was Marja’s grandfather, Hannes, continued Sakari’s work. Hannes had five sons, all of whom made wheels. Two of them, Nikolai and Gideon, stayed home and worked as carpenters through their lives, including working on renovations of the old church in Keuruu. I assume it is this church, famous in the area, originally built in the 1750s.

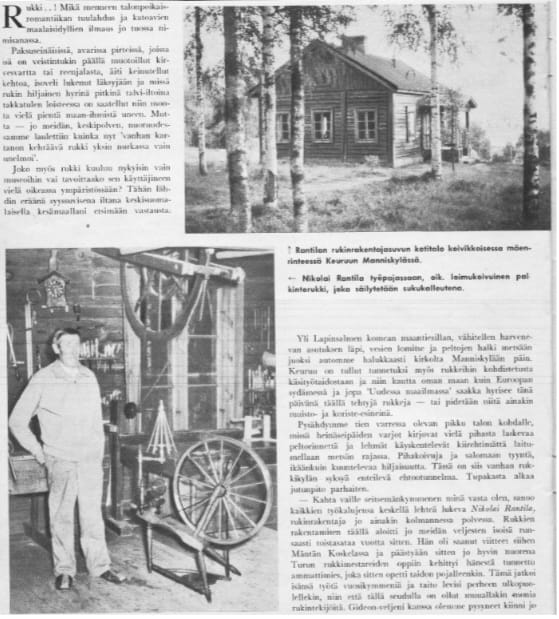

This link has photographs of the incredible painted woodwork inside: Travels in Finland and abroad. Nikolai lived to age 94 and continued in his old age to make small wooden objects. Marja shared this article with the Rukkitaivas group, from a 1958 Pellervo magazine in Finland.

The picture in the article shows the Rantilas’ house, where her father was born and the wheels were made. The man showing the wheel was Nikolai.

The woman spinning was Gideon’s wife, Auna. Unfortunately, the text is blurry, but Sauli and Marta provided the key information from it. This is a wheel made by Hannes in 1931, which appears to be identical to mine, except for the stain color.

The Rantilas were not the only wheel makers in Keuruu. Another branch of the family also made wheels. Nikolai’s grandfather, whom I believe was named Adam (Aatami), had a brother, Samuel Kingelin, who along with his son, Samuel Saukkomäki, also made wheels. The wheels were quite similar, with just slight differences in their decoration.

With all of the hours I spend researching spinning wheels, following fruitless leads and hitting dead ends, it felt slightly surreal to have this rich trove of wheel history fall into my lap as the result of a single facebook query. And it adds a whole layer of richness to spinning on wheel when you know something of its maker and history.

While I cannot be absolutely certain that my wheel was part of the 1922 batch that Hannes sent to America, chances are good that it was. My wheel looks as if it was never touched for spinning, but always used as decoration. That makes sense, since hardly anyone still spun on wheels in the early 1900s in this country. It seems more likely that someone would have bought one of Hannes’ shipped wheels once it was here, rather than taking the effort and expense to personally ship the wheel over from Finland. But, however it arrived, it has been lovingly taken care of since then.

I would love to know the reason Hannes Rantila marketed these wheels in America in 1922. Were they a decorative Scandinavian touch for homes at the end of the Arts and Crafts movement? A taste of a Carl Larsson interior, perhaps? Because, if ever a wheel elevates traditional craftsmanship to art, this one does.

It has a graceful, low-to-the-ground stance, with scooped cutouts under both sides of the table.

The far side cutout has the remains of what looks like a paper label. The stain finish is uneven, so I wonder if the wheels were shipped here unfinished, to be stained or painted as the customer desired. Turnings, angles, and curves are juxtaposed into a happy web of parts.

The large treadle has curves and swirls cut into the edges

and is attached with a swooping bar,

both features found in earlier Finnish wheels.

The turnings on the maidens and spokes are harmonious and eye-catching.

The spokes are pegged through the drive wheel rim, which has a wide single groove for the drive band.

The drive wheel is constructed of six joined pieces with radial edges.

The uprights have deep cuts for the axle,

capped with decorative pegged inserts on both sides.

Thick guy wires run from table to uprights—again a characteristic of some older Finnish wheels.

The upright ends are threaded.

One of the most interesting features of this spinning wheel is that it is designed to accommodate two different sized flyer assemblies.

Some Scandinavian wheels accomplish this by having two-sided leather bearings, which can hold different sized flyers on either side of the maidens. Others have a spinner-side maiden that slides back and forth on the mother-of-all, so that shorter and longer flyer assemblies can be switched out. This design is a little different.

There are two holes on top of each other in the spinner-side leather bearing and two looped bearings on the far side.

The leathers are sheared flush with the maidens in the back and the double-holed one has two small wooden pegs securing it through the side of the maiden.

There is an extra hole in the mother-of-all so that the spinner-side maiden can be moved closer to the other maiden.

That maiden has a small, easily removable peg in the bottom.

This design allows the spinner to readily change from a large bobbin and flyer assembly to a smaller one. My wheel came with only one flyer. It is humongous.

I cannot imagine spinning flax on it, so I am assuming that the large flyer was intended for wool spinning and a smaller one for flax spinning. It is also possible that the larger flyer assembly was used for plying. Whatever the intent, it is a nice, ingenious set-up.

The crowning touch, of course, is the distaff. It tops the wheel like a perfect Christmas tree.

The wheel is just so over-the-top pretty, when I brought it home I was little apprehensive about how it would spin. I knew nothing about the maker then, so feared it might have been made more for decoration than for spinning. It only took a few treadles, however, to realize that this wheel was a true Finnish production wheel, designed to spin with ease and speed.

It is pure pleasure to look at and to use. Thank you Hannes.

And great thanks–kiitos–to Marja and Sauli. I apologize if I muddled any of the details in translation.

Update, March 23, 2022:

I learned a little more from Marja about the Rantilas. She told me that Hannes Rantila won a First Prize for his wheels at the 1922 Exhibition in Tampere, Finland. I found a piece describing the Tampere Exhibition: “Plans had also been made to organise the 12th general agricultural fair in Tampere in 1922. Eventually that fair merged with the third national fair, albeit in a truncated form. The architectural design for the fair was commissioned from architect Alvar Aalto. The fair exhibited mainly products from the wood industry and the home industry as well as the machining industry. The audience could also see competitions related to craftsmanship and exhibitions ranging from carving a shaft of an axe to patching a pair of mittens. The stands of Tampere businesses received much attention.” (for citation, see below). After Hannes’ win at Tampere, he received an order from a businessman (arranged through a brother in Kuopio) for 10 spinning wheels to be sent to America. After sending the first shipment, more were ordered and Hannes eventually sent a total of 25 wheels. I believe Hannes also sent some wheels to Germany.

Also interesting is the family name. From what I understand, in the early- and mid-19th century, surnames were fluid, even for an individual, and Finnish families did not have fixed family surnames. So, each individual in a family might have a different surname—some patronymic, some based on a trade, or place. When Sakari, Marja’s great-grandfather, started making wheels in 1845, believing a craftsman should have a fixed surname, he chose “Rantila” based on a shortened version of the name of the beach estate where he lived. It is an unusual surname and his wheel-making son and grandsons all kept it. As a result, these wheels can accurately be referred to as Rantila wheels.

The quote above is from: Hietala, Marjatta; Kaarninen, Mervi, “The foundation of an information city : education and culture in the development of Tampere,” (Tampere University Press, 2005).

She is a treasure. I enjoyed learning her history and know you will enjoy spinning on her.

LikeLike

Isn’t amazing to have that history? So often, even if we know the maker, we do not get the kind of information here, with being to see where the wheel was actually made. I’m still learning more from Marja, but wanted to get this posted while the history was fresh in my mind. Thanks for your comment!

LikeLike

What a wonderful treasure. I’m so glad you found it. You are one of the few who will appreciate it.

The drive wheel looks relative large. Is it? Do you know the ratios? Does it spin a fine yarn fast like the Quebec wheels do?

LikeLike

Yes, the drive wheel is relatively large. I don’t know the ratios but these Finnish wheels are similar to the Quebec wheels made in the same time period. They were designed for fast, efficient spinning.

LikeLike

What a WONDERFUL treasure. ❤️

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

It’s not often that we have this kind of history for a wheel. It does feel like I discovered treasure.

LikeLike

Previous message sent by accident! Just wanted to say what a great blog post. And a gorgeous wheel. Susanne

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Thanks Susanne. It is a spectacular wheel and it has been so exciting to learn about the Rantila family. I am still learning more.

LikeLike

This is a gorgeous wheel and the fact you found such a detailed history is a tribute to the fabulous part of the internet that doesn’t get the press it deserves. Wow.

LikeLike

Exactly. That is such a good point. The international aspect, in particular, of blogs and facebook is tremendously enriching. Imagine trying to find out anything about this wheel 20 years ago. And, now I have the maker’s granddaughter bringing its history alive.

LikeLike

Yup. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person