Perhaps the most readily identifiable Pennsylvania wheel is the “Irish castle” wheel. Its distinctive style is best described by collector, Bill Leinbach: “The vertical lines, the splay of the long legs, the relationship between the drive wheel and the flyer bobbin assembly, all contribute to the magnificent display of this tripod temptress.” (Leinbach, SWS p. 6)

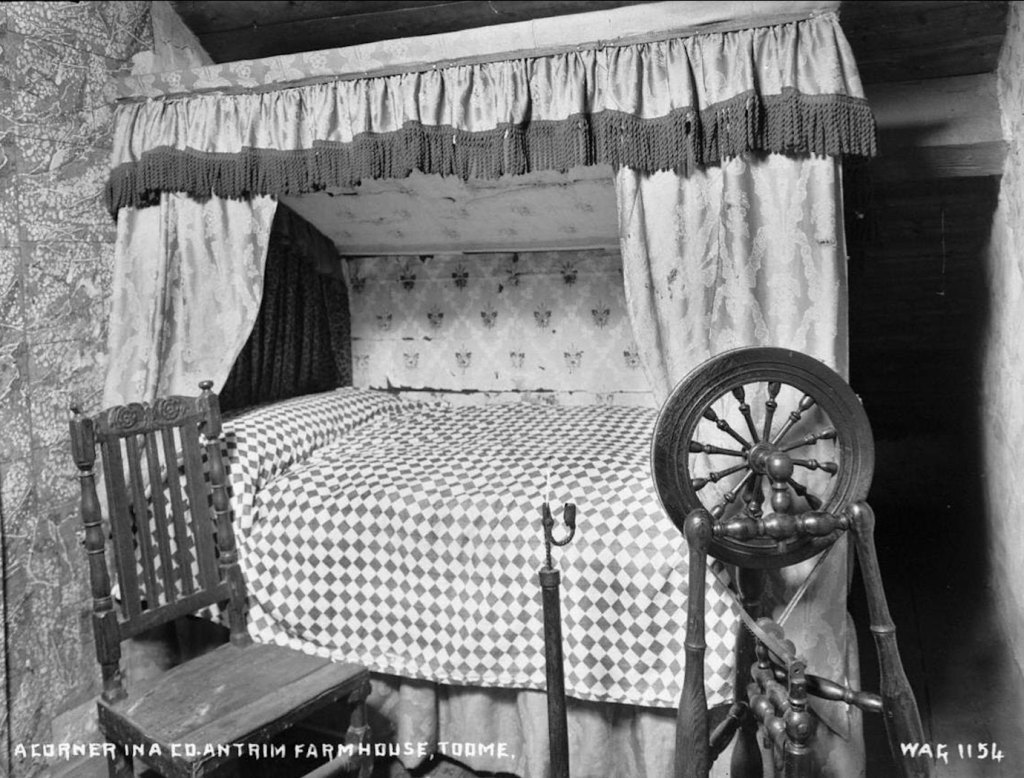

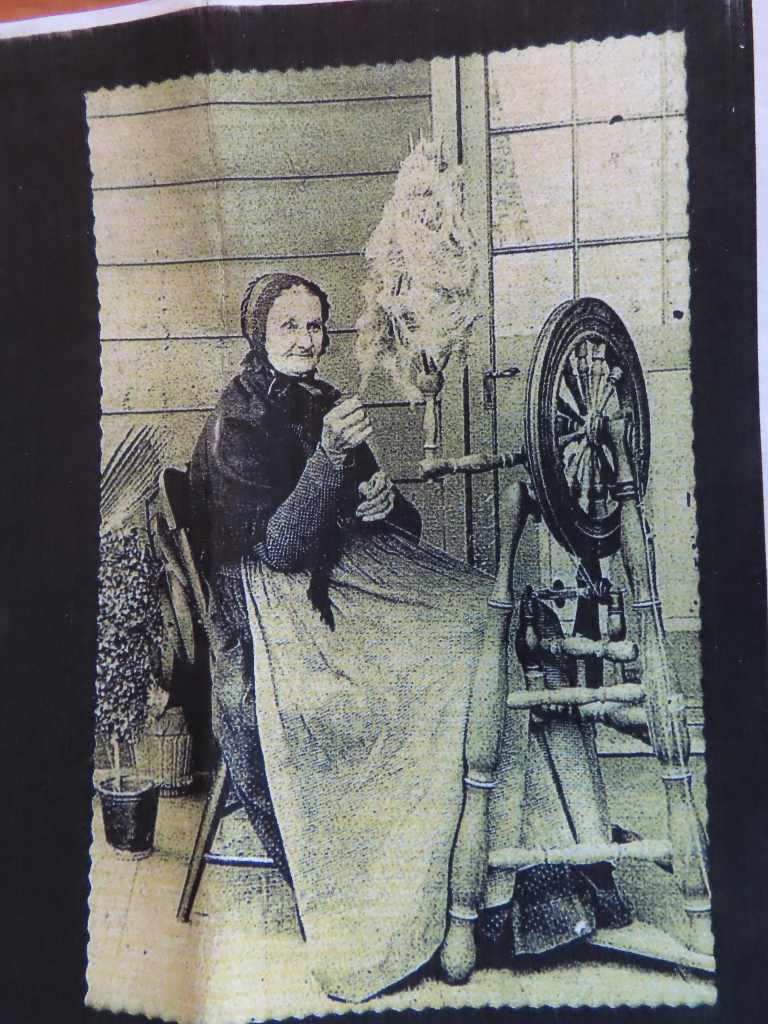

Aside from its harmonious lines, its height is impressive and its design practical, with long hefty legs providing a solid base with a small footprint. The solidity and stability allows for steady, even spinning, while the small footprint is welcome in tight living quarters.

While this wheel style has been found occasionally in other parts of this country, it flourished in Pennsylvania. Why and how this Irish wheel design was adopted by Pennsylvania German wheel makers remains something of a puzzle. Some have speculated that this style may have originated in Germany and migrated to Ireland, with the “castle” name having derived from the German town “Kassel.” (P&T, p. 56) On the other hand, wheel collector John Horner suggested that these wheels are named “castle” because of their shape and are “peculiar” to Ireland. (Ulster Museum, P. 21)

Patricia Baines notes that in Britain castle wheels refer to vertical wheels in which the drive wheel is above the flyer mechanism, with Scotland having its own castle wheel, different than the Irish. (Baines, p. 45). Whether born in Ireland or not, the sturdy three-legged Irish castle wheel was an integral part of 19th century life in northern Ireland, especially in Donegal and Antrim counties, used early on for flax and later for wool spinning into the 20th century. (Baines, p 144-46, P & T, p. 53)

While some castle wheels were brought over from Ireland to Pennsylvania and other states, the majority that we find in this country appear to have been made here, primarily by Pennsylvania wheel makers of German descent.

Probably the most well-known is Daniel Danner, who signed and dated many of his wheels with a paper label pasted onto the back leg. Of course, most of those labels have not survived, but his wheels have distinctive qualities that identify them as Danner wheels.

Danner was born in Manheim in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in 1803. His father, Adam, was a weaver. Daniel married Elizabeth Hartman in 1833 and they had five children, only two of whom survived to be adults. (Leinbach, SWS, p. 6)

Fortunately, Danner kept daybooks, which show that he made wheels for over 40 years, from 1821 until at least the early 1860s. He made great wheels, saxony-style wheels, and what he called “cassel” wheels. Perhaps this was a phonetic spelling of “castle” (his daybooks were written in English, not German), or it could be an indication that these wheels did have a German origin. As with so many spinning wheel makers, Danner was not limited to wheel making, but made and repaired all types of household and farm items, including reels and swifts. About forty percent of his wheels were castle wheels, which he priced at $4.00, fifty cents more than his regular flax wheels.

There is no definitive answer as to why Danner and other Pennsylvania Germans were making Irish Castle style wheels. Perhaps there were similar wheels remembered from Germany—although I am not aware of anyone actually identifying a German wheel of this style. Perhaps he was influenced by an Irish wheelmaker, such as Samuel Humes. Humes, born in 1753—considerably older than Danner–came to Lancaster County from Antrim, Ireland. Danner’s saxony-style flax wheels were very similar to Humes’ wheels, almost copies.

Whether he did this with Humes’ permission or not remains a question. I am not aware of evidence that Humes made Irish castle wheels, but it is certainly a possibility and other wheel makers in the area, including Danner, may have copied the style from him. It is also possible that Irish Castle wheels were simply a response to market demand.

When I started digging into genealogy research on Danner, I found several family trees on ancestry.com that had Danner’s father, Adam, as born and living part of his life in Shelby, North Carolina. Because that is a region with many Scots-Irish immigrants, I was excited to think that might offer some explanation for Danner’s adoption of this style.

As it turns out, I believe that is a different Adam Danner and Daniel’s family likely did not venture outside of Pennsylvania. But it got me looking into Scots-Irish settlement in Pennsylvania and I found Scots-Irish immigrants from Antrim and nearby counties settled in many of the same areas in Pennsylvania as the Germans.

Perhaps they sought this style wheel from the local German wheel makers. While I have only seen a few pages of Danner’s day book, in those, it appears that the surnames of most of his customers were of German origin, but with a smattering of English and Irish names, including “a new flyre” for Barb Donoven. (McMahon, p. 16). So, it is possible that, at least initially, these wheels may have been made for Irish customers seeking this wheel style. We just do not know.

While probably the most well-known, Danner was not the only one making this style wheel in Pennsylvania. Some did not sign their wheels and will remain a mystery. Samuel Henry, however, another maker of German descent, did stamp his name on at least some of his unique and elaborate castle style wheels—quite different from Danner’s.

Another intriguing maker is usually referred to as the “Landisville” maker because several of his wheels showed up in that area of Pennsylvania.

According to Bill Leinbach, Clarke Hess, a well-known Pennsylvania historian and collector, believed that perhaps the Landisville wheels can be attributed to Johannes Berg or his son Jacob Berg, based at least in part on probate inventory records. Hess died several years ago and his extensive collection was auctioned off. In Lot 5525 of Clarke’s on-line auction collection, a sampler was identified as made by Maria Berg, daughter of “Turner” Jacob Berg of West Donegal Township, son of immigrant Andreas Berg. I do not know if this is the same Jacob Berg that Clarke had been researching—there are multiple Jacob Bergs in Lancaster County–but it is a clue worth pursuing.

Donegal Township had a large number of Irish settlers, so might have been fertile ground for these wheels and is not far from where Danner was making his wheels in Manheim, Pennsylvania. That may be important because, apparently, multiple wheels have been found with bodies made by Danner and drive wheels made by the “Landisville” maker. Bill Leinbach suggests that may indicate that they knew each other or even worked together at some point. This is an area ripe for more research.

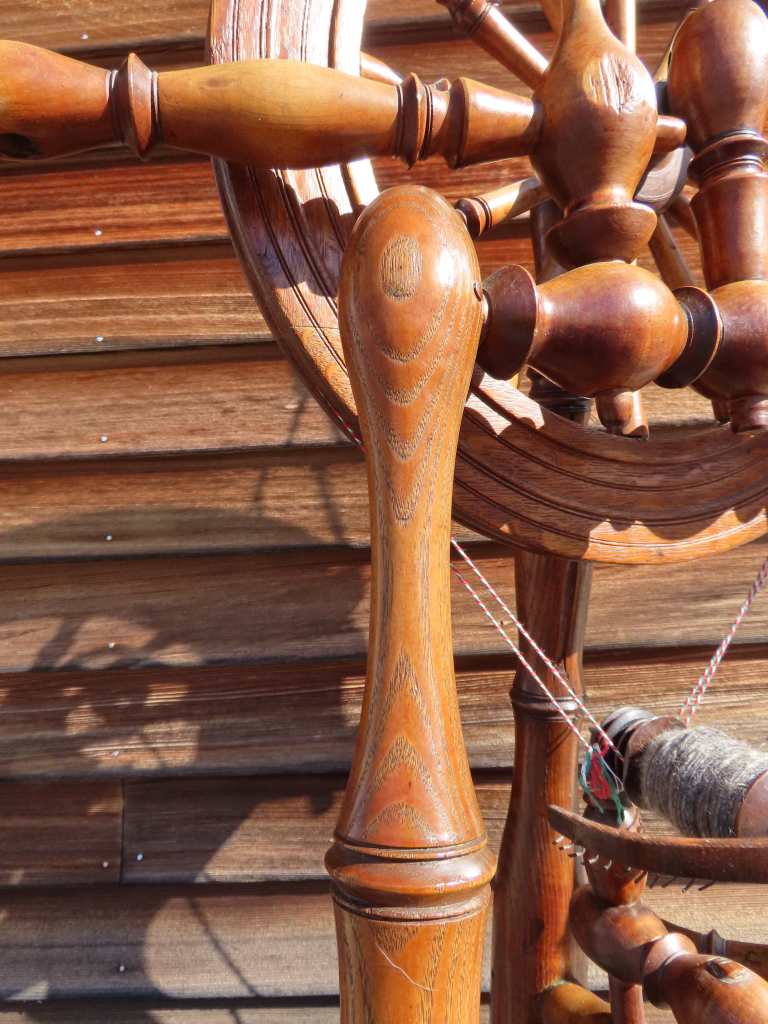

My wheel, Elizabeth, which came from Bill Leinbach, is one of those combination wheels. The body has classic Danner features, but the drive wheel appears to have been made by the Landisville maker. Danner’s drive wheels were made of four equal pieces and had “shotgun shell and olive” spokes—a perfect descriptive term because that is just what they look like.

The Landisville/perhaps Berg maker constructed his drive wheels with two long and two short sections (felloes) and spokes closely resembling those on wheels from Ireland—they look like wine goblets to me.

For an excellent visual comparison and description of wheels made by Danner, the Landisville maker, and Samuel Henry, I recommend Michael Taylor’s article “Castle Wheels in Lancaster County, PA.” listed below.

While there is no label on my wheel, the body appears to be a beautiful example of Danner’s work. The long flat treadle fits around the back leg,

and is attached to the axle with a long cord and leather top—typical of Irish wheels.

While the legs are heavy, they are gracefully curved and highlight the wood grain.

The top cross bar has two holes. Danner traditionally used one for the distaff and the other for a reeling pin. Having two holes allows the spinner to place the distaff on either side and also provided a place to mount a water dish for flax spinning. I am fortunate to have two distaff supports, one on each side.

Danner had some variations in the turnings for the distaff supports. I believe the left hand one is typical of Danner’s wheels,

but am not sure if the other one is also made by him or some other maker.

The flyer set up is ingenious.

One wooden key releases the end flyer bearing so that the flyer can be removed.

The other raises a central bar to control tension.

The flyer hooks are seated opposite to most flyers, in other words, the hooks are on the top right side and lower left side of the flyer when looking down the arm, in contrast to the usual configuration of right on top of the left arm and below the right.

According to Patricia Baines, this was the way the flyers were usually made on castle wheels in Ireland. She suggests that this may have originally been to facilitate spinning flax in the “S” direction. (Baines, p. 146) It is interesting to see how that unusual feature seems to have been carried over from Ireland to many of the castle wheels made in Pennsylvania.

While most makers of these wheels were in Pennsylvania, a few wheels have appeared in New England, too, including one signed “M. Wood.” That name is intriguing because we know of two New England wheel-making brothers, Phineas and Obadiah Wood (see previous post “Scarlet”). Could M. Wood be related?

There is still so much research to be done on American castle wheels—to pin down who made them and why. But there is already a tremendous amount of research that has been done. I only skimmed the surface here. The articles and books listed below were my references and contain much more in-depth and complete background and analysis. I highly recommend them.

Descriptions and photographs do not do justice to the beauty and fine craftsmanship of this wheel. A heartfelt thank-you to Bill Leinbach for entrusting me with this amazing wheel, for his generosity in sharing time and knowledge, and for the photograph of Elizabeth Danner.

References:

Leinbach, William A., “Daniel Danner: The Man Behind the Wheel,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue 4, January 1994, pp. 6-8.

McMahon, James D., “Daniel Danner Woodturner: An Early 19th Century Rural Craftsman in Central Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania Folklife; Vol. 43, No. 1, Fall 1993., pp. 8-19.

Taylor, Michael, “Humes, Danner, and Killian Flax Wheels,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue 35, January 2007, pp. 2-4.

Taylor, Michael, “Castle Wheels in Lancaster County, PA,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue 93, July 2016, pp. 2-4.

Baines, Patricia, Spinning Wheels, Spinners & Spinning, B. T Batsford, Ltd, London, 1977, pp. 144-46.

Pennington, David and Taylor, Michael, Spinning Wheels and Accessories, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA 2004, pp. 53-59.

Thompson, G.B., Spinning Wheels (The John Horner Collection), Ulster Museum, Belfast 1976.

Ancestry.com for genealogies of the Danner and Berg families in Pennsylvania.

What an amazing, beautiful wheel. Such craftsmanship.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s so beautifully made–all parts. I love the Danner body, but have to say, I think the spokes on this drive wheel are lovelier than the shotgun shell and olive ones that Danner used. It makes for a spectacular wheel.

LikeLike

Cassel is also a last name. I spent several years surveying Cassel Cave.

<

div>Pat

Sent from my iPhone

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Interesting that you should mention that. There is a Casselman River area in Pennsylvania and I researched it to see if there could be some German Cassel family or place connection with these wheels. I came up empty, though.

LikeLike

I don’t know if the wheel’s origin is Scotch/Irish or German, but I know that the Scotch/Irish, the historical American term for the people called Ulster Scots in Ireland, opened the Pennsylvania frontier. I’ve traced my ancestors back to the late 1700s in Cumberland County.

My great grandfather, Jonathan Jacobs, left an estate inventory when he died in 1844 that included a spinning wheel which I assume my great grandmother, Mary Ferguson, spent hours spinning on. I wish I knew what style it was.

LikeLike

I, too, have Scots-Irish ancestors that settled in Pennsylvania–from Ballymoney, smack in the middle of flax/linen country. One of the fun aspects of doing these blog posts is following different research trails. It was fascinating to see how many areas had German and Scots-Irish settlers side by side. Many of those that settled in Shelby County, NC came there after originally living in Pennsylvania.

Antique wheels can be a good marker for settlement patterns. As you said, the Scots-Irish (Ulster Scots) opened up the PA frontier and much of the Appalachian frontier farther south. It’s interesting that we don’t seem to see Irish Castle wheels in Appalachia. In fact, there don’t seem to have been many Irish wheel makers in this country who made Irish-style wheels, castle or otherwise. Thank goodness the Pennsylvania Germans decided to make these.

LikeLike

Off hand do you know of anyone making flyer wheels in Appalachia? Have many been found there? I always associate Appalachia with walking wheels, but maybe I’m wrong.

LikeLike

No, I don’t know of any southern Appalachian flyer wheel makers. Most old photos from the area show walking wheels, but an occasional one will show up with someone using a flyer wheel. I suspect that there wasn’t enough flax grown in southern Appalachia to support a big demand for flyer wheels. I know it was grown in some cooler areas of the southern mountains, but I don’t think the amount approached anything like Pennsylvania, New York and New England. So, if most spinning was wool and cotton that could explain the prevalence of great wheels.

LikeLike

Thanks !

Sent from Mailhttps://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkId=550986 for Windows

LikeLike

The photo below this sentence catches my eye:

I believe the left hand one is typical of Danner’s wheels,

The distaff support shows unturned wood fibres indicating a blank too small for the desired finished piece. In the case of Horton Row this often happened. My own interpretation is that he was parsimonious using every bit of his raw material that he could. Some might consider the raw surfaces a blemish (depending on viewer) or damage (not).

What caught my eye is that in the left position this support presents the raw fibres to the view of the spinner. If placed on the right side this support would not show the raw fibres to the spinner. I expect the current positions are as you found them and consistent with my own preference to leave things as close to in situ as possible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great observation Gordon. I have seen this on other wheels but didn’t know the reason for it. I am always delighted when I see parsimonious use of wood–knots, bark–it all works! I do not know which side this distaff support was on originally but I do not view it as a blemish, rather extra character, so keep it where I can see it.

LikeLike

In Lot 5525 of Clarke’s on-line auction collection, a sampler was identified as made by Maria Berg, daughter of “Turner” Jacob Berg of West Donegal Township, son of immigrant Andreas Berg. I do not know if this is the same Jacob Berg that Clarke had been researching—there are multiple Jacob Bergs in Lancaster County–but it is a clue worth pursuing.

Yes, this is the same Jacob Berg that Clarke was researching. I knew Clarke well. Andreas Berg purchased land in Donegal Township, Lancaster, PA. His son Jacob inherited that land.

LikeLike

Fantastic! Thank you so much for taking the time to confirm this. I wish that I had been able to talk to Clarke about this and pick his brain. I understand from Bill L. that Clarke had found probate records showing wheel making tools passed from father to son. Do you know what other sources Clarke had for his research on the Bergs?

LikeLike

I have been reading this thread and want to add my 2 cents. I have a flax wheel signed by B. Cornyn Pottstown. It is in very good condition and very old. I have traced the family back to 1802 when a Domenick Cornyn came to Pennsylvania from Limerick, ireland. The census called him a “turner” for his trade. He was the father to a Bernard Cornyn twenty years after he came to Pa. The family lived in Pittsburgh pa for an extended time. This wheel is a little gem with all the original parts and it spins. Does anyone know of the Cornyn family or these 2 turners?

LikeLike

Wonderful. I know there is some discussion or B (and P?) Cornyn on Ravelry in the Antique wheel group. I’m about to head out of town, so won’t have time to look at it, but will get to it next week when I’m home. Or, if you are on Ravelry, you can do a search for “Cornyn” in that group and will find the info.

LikeLiked by 1 person