Most antique wheels are a puzzle—wood and metal conundrums. Who made them? Where, when, and how were they made? Who used them? For what and how were they used? Because so little of this information was written down, most often we rely on clues from the wheels themselves to try to answer these questions.

But some clues are confusing. In contrast to most wheels, this one advertises her maker and time—IS McIntosh, 1857.

How exactly she was used, however, is a mystery. There is no doubt that she was heavily used. But, in addition to expected wear, she has unusual scars that are somewhat bewildering. It feels as if she is trying to tell us something, but we lack the ability to translate it.

She is the second wheel that I ever bought and I almost passed her by. I found her deep in a crowded, dark antique store barn one town away. Brand new to antique wheels, I obediently followed the oft-heard instruction to check the drive wheel for wobble, which supposedly indicated a warped wheel. This wheel had an extreme wobble, veering one way and then the other.

So, even though I could see a name and date, I gave the wheel a pass, thinking it would be unusable. In the months that followed, though, I could not get her out of my mind. I decided to check her out more closely and found that whatever the reason for the wobble, it was not due to warping. So, when the owner offered her for a song, I brought her home, determined to get her spinning again.

She was filthy—absolutely encrusted in black grime. And, it turned out that the wobble was caused by a bend in the straight end of the axle. Thanks to advice from David Maxwell (aka TheSpinDoctor) on Ravelry, after securing the drive wheel in a flat position, I used a pipe for leverage to straighten the axle end. It worked beautifully.

Cleaned up, axle straightened, oiled, with a new footman made by my husband—she was ready to try. And, as those of you who rescue wheels know, that first spin after bringing a neglected wheel back to life is hard to describe without sounding overly romantic and ascribing human-like qualities to the wheel (it feels like she’s thanking me!).

But with your feet and hands feeling the imprint of past users, it is almost intoxicating when the wheel settles into its old work rhythm.

Not only is it satisfying, but there is an undeniable feeling that bringing such a marvelous little machine back to its purpose connects you with all the women who used the wheel in the past. It is a good feeling and an addictive one. This filthy, wobbly wheel set the hook, making me a sucker for wheels that cry out to be rescued.

Once I had her spinning, I set out to find out more about her maker, IS McIntosh. Coincidentally, the same person who had given advice on the bent axle, David Maxwell, also is the McIntosh wheel specialist. His research is set out in an article in The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, cited below. As David explains, there are three versions of McIntosh marks—”Alexr McIntosh,” “McIntosh,” and “IS McIntosh.”

He has documented marks from 1798 to 1892–almost one hundred years. From genealogical research, David surmises that the “Alexr” marked wheels were made by Alexander McIntosh, born in Scotland, and emigrating to Canada in 1803. The earliest marked “Alexr” wheel, a double flyer, likely was made in Scotland. Alexander eventually settled in Pictou County, Nova Scotia and his known marked Nova Scotia wheels span the years from 1811-1824.

From the wheels David has been documenting, from 1829 until 1886 wheels appeared marked simply with “McIntosh.” From 1852 to 1892, the “IS McIntosh” wheels were being produced. And, starting in 1863 until 1879, the Alexr stamp again was used.

David Maxwell’s research found that Alexander’s son John apparently joined him as a wheel maker, which likely resulted in the mark’s change to simply “McIntosh.” But both Alexander and son John died in 1846. At some point, before or after 1846, Alexander’s grandsons (John’s nephews), named Alexander and James, also became wheel makers.

David’s theory is that Alexander Jr. carried on making wheels under the “McIntosh” stamp after his grandfather and uncle died, joined by his younger brother, James. In 1857, it’s probable that James started marking his wheels with the “IS McIntosh” stamp (the letter “I” often used for the letter “J” in maker’s marks) and then brother Alexander starting using the “Alexr McIntosh” stamp again. For much more detail on this, please refer to David’s article.

No matter which McIntosh was making the wheels, they all share similar features. The treadle bar has a spoon-shaped end, with a ridge underneath.

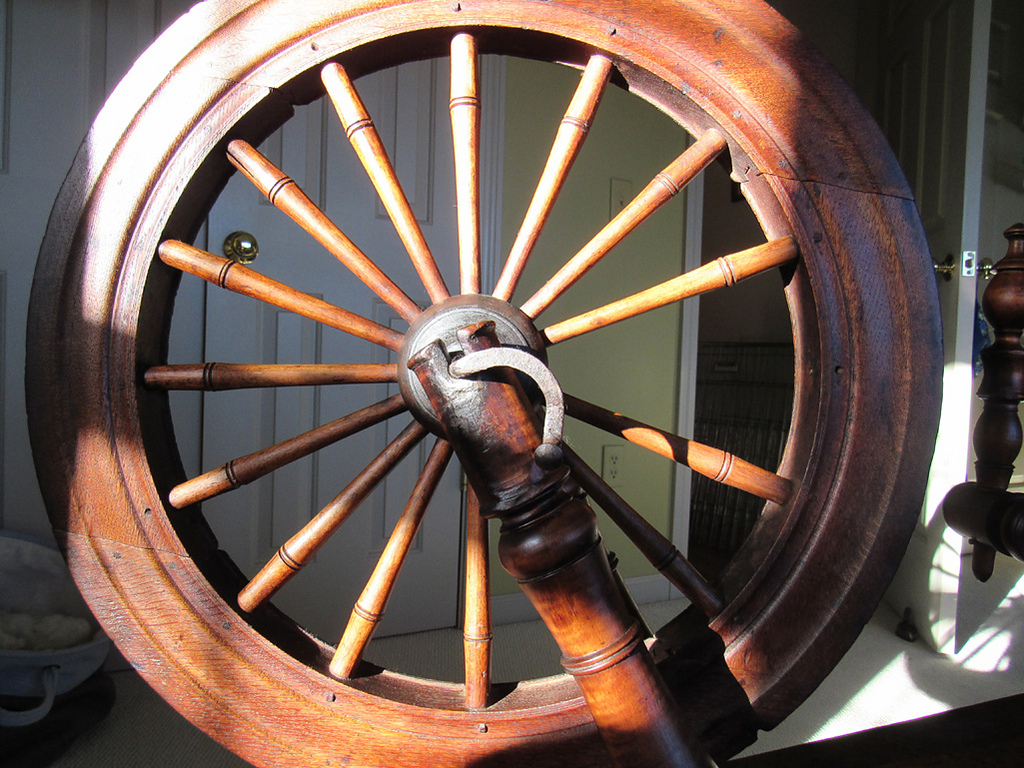

The drive wheels have 14 or 16 spokes—mostly 14 on the earlier wheels and 16 on the later ones, with some exceptions.

The tables have a hole for the distaff, an angled end under the drive wheel, and understated, tasteful turnings.

The wheels were popular and well-made, apparently spawning imitators. Unmarked wheels often turn up that look very similar to McIntosh wheels, but with some slight deviation.

My wheel, Marilla, while a typical McIntosh, has her own unique features. Her maker, IS (likely James) was economical with wood and his time.

The wood on one leg and the MOA collar still retain some bark.

The sides of the table are quite rough

and the underside has a series of indented lines, whether from a saw, a plane, or something else, I do not know.

The wheel is made from heavy wood and the drive rim is quite wide.

There is a nail in the non-spinner side leg, with no apparent purpose (it is not on the bottom to keep the wheel from sliding).

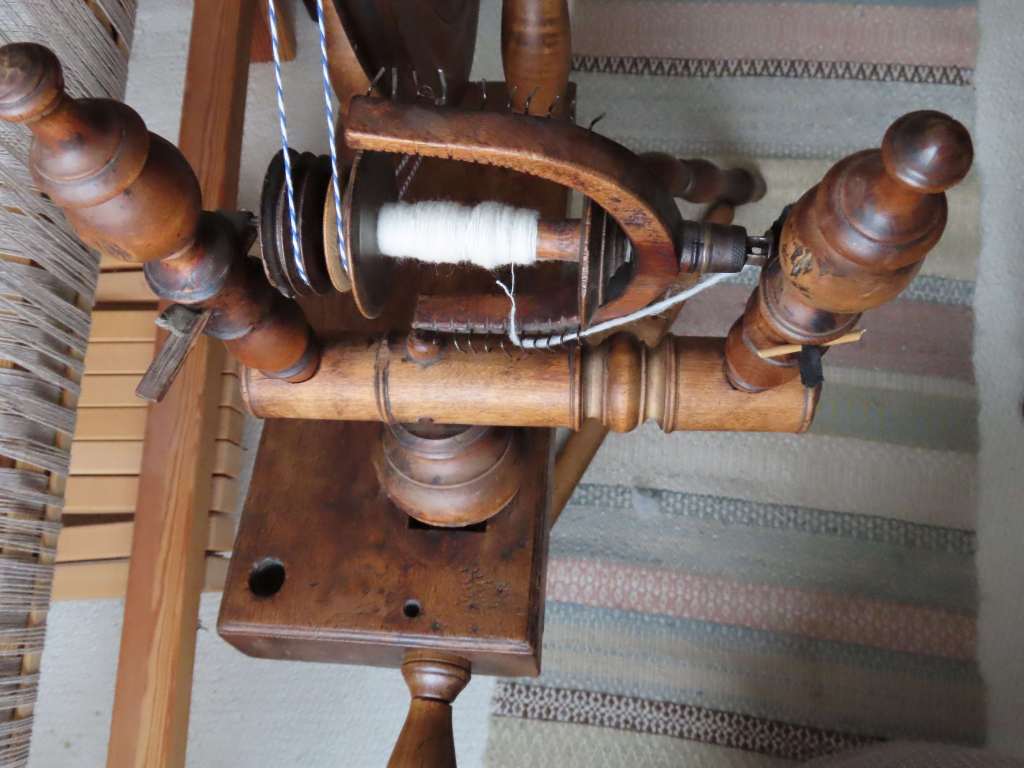

The orifice is fluted, something found on other McIntosh wheels, but not all.

And, probably to “repair” a crack where the mandrel runs into the flyer, a thimble (with the bottom cut out) provides an ingenious and long-lasting binding.

It is such a personal touch, this thimble fix is one of my favorite things I have ever found on an antique wheel.

When I brought the wheel home, the bobbin had some very old, beautifully spun wool on the bobbin—a seriously good spinner last used this wheel. The flyer has typical wear marks

and the treadle a lovely smooth worn curve from years of treadling.

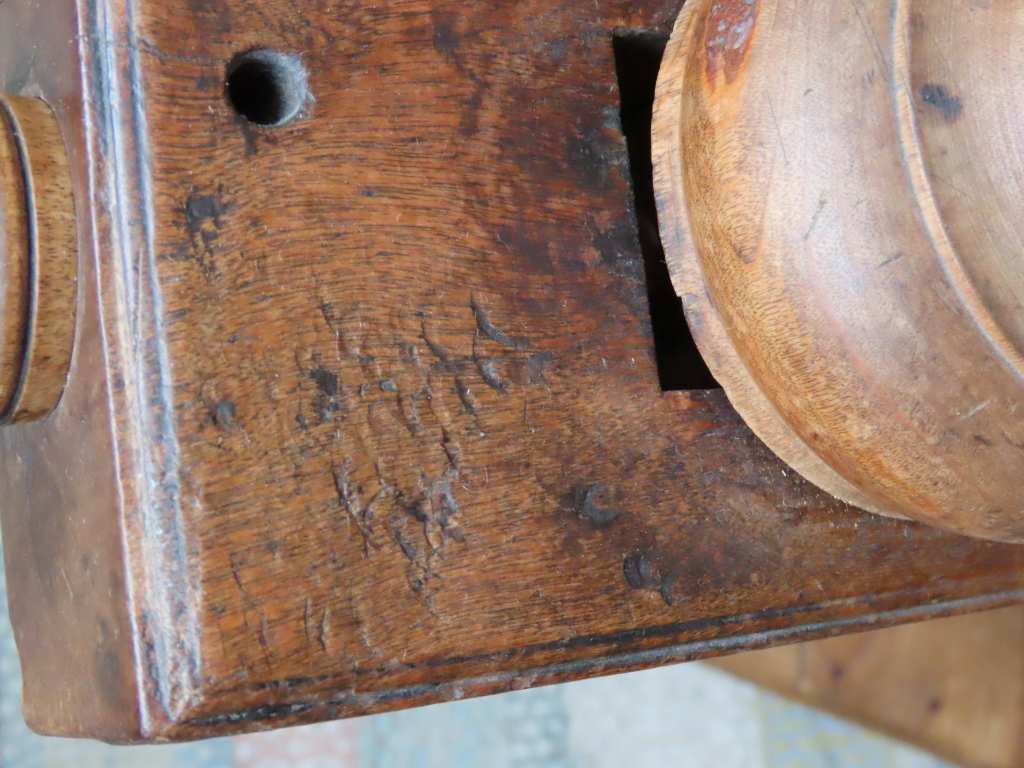

But other wear marks have me flummoxed. On the end of the table around the maker’s mark and on areas of the table, there are crescent moon-shaped gouges.

Occasionally, similar marks are found on other wheels. While no one seems to know with certainty what they are, speculation is that they might be from the spinner tapping the orifice end of the flyer, perhaps to loosen the bobbin for removal.

But, in this case, there is a whole valley gouged out of the table, where apparently something struck the surface repeatedly for a long time.

Even more perplexing are the marks on the spokes.

They are only on the spinner side

and are angled, short lines–some straight, some slightly curved–on the outer 2/3 of each spoke.

I have seen two other wheels on Ravelry with somewhat similar marks, one a Norwegian-style wheel found in Saskatchewan and the other a Finnish-style wheel found in Leningrad. There is a thread named “Mystery Scratches” in the Antique Wheel group on Ravelry discussing the marks on these three wheels, with a variety of guesses as to their origins.

While many of the guesses were that they are damage unrelated to spinning (child hitting with a stick, dog chewing, odd storage), I believe they are wear marks from some type of long term use either in spinning, winding off, or warping, but try as I might, I cannot figure out how they came to be. If anyone has suggestions, please let me know. I would love to solve the mystery.

Finally, in addition to Marilla, I was fortunate to find another McIntosh wheel several years later, this time an early 1815 Alexander.

I named that wheel Margaret and she has since moved on to another, very good home.

I only took a few photos of her, but it is interesting to compare her to the later IS wheel.

She is a beauty

but has her own table gouge, this time the typical one found under the drive band.

Here is a photo taken in Vörå, Österbotten, Finland sometime between 1920 and 1960 (link here) of a knife used in this way.

There is speculation that the knife kept the drive band cross from migrating to the top when spinning counterclockwise, so that the band would be less likely to grab flax from the distaff. But, at this point, that remains speculation. As this wheel shows, these knife marks are not just found on Scandinavian wheels, as many think, but on wheels from a variety of places and cultures. Whatever the purpose of the knife, it was important enough that spinners did not mind creating a big gouge mark in their wheels. As more and more photographs become available online, I hope that we will discover more about what the marks mean and how these wheels were traditionally used.

Thank you to David Maxwell and his sources for all of the research he has provided on McIntosh wheels.

You can find much more information in the Antique Spinning Wheels group on Ravelry, including a list of all the wheels David has been able to document.

Here is David’s article, with a wealth of information that I did not include here:

Maxwell, David, “The McIntosh Family of Spinning-Wheel Makers,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue 108, April 2020, pp. 2-5.

Also thank you to AlltFlyer on Ravelry for the photograph of the knife in the table.

The thimble took my breath away! As you mention, it is the fixes and repairs that add humanity to the piece. That often speaks to me through the foot imprints found on a treadle. The gouges in the wheel spindles speak to me of an inexperienced apprentice using a spoke shave. Odd that the signs only appear on one face of the wheel.

Thank you for another great article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The thimble really sparks my imagination. It would make a great kids’ book, where you follow the an object through all it’s different lives with different people. It outlives them all in its final incarnation on a spinning wheel. As for the spokes, some people suggested that that marks were made by a lathe. I don’t think the lathe or spoke shave theory hold, though, because they are only on the front side and, seeing them in person, they just don’t look like marks made while constructing the spokes. I had actually wondered if the spinner might always worn a thimble on her right hand (or had a hook for a hand) and the metal hitting the spokes when she started the wheel might have made the marks. But it seems pretty unlikely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an astounding article! Love the photograph of the knife stuck in the table and that these were made as tools, not fine furniture. And the thimble. Oh wow. That’s worth the price of the entire wheel!

LikeLike

That photo is the first one I’ve seen (I think) of the knife in the table. I really am hoping that we will turn up more old photos that help us to understand the wheel and spinning practices that we have lost. Even posed photos can be educational for us. As for the thimble, it makes this wheel invaluable.

LikeLike