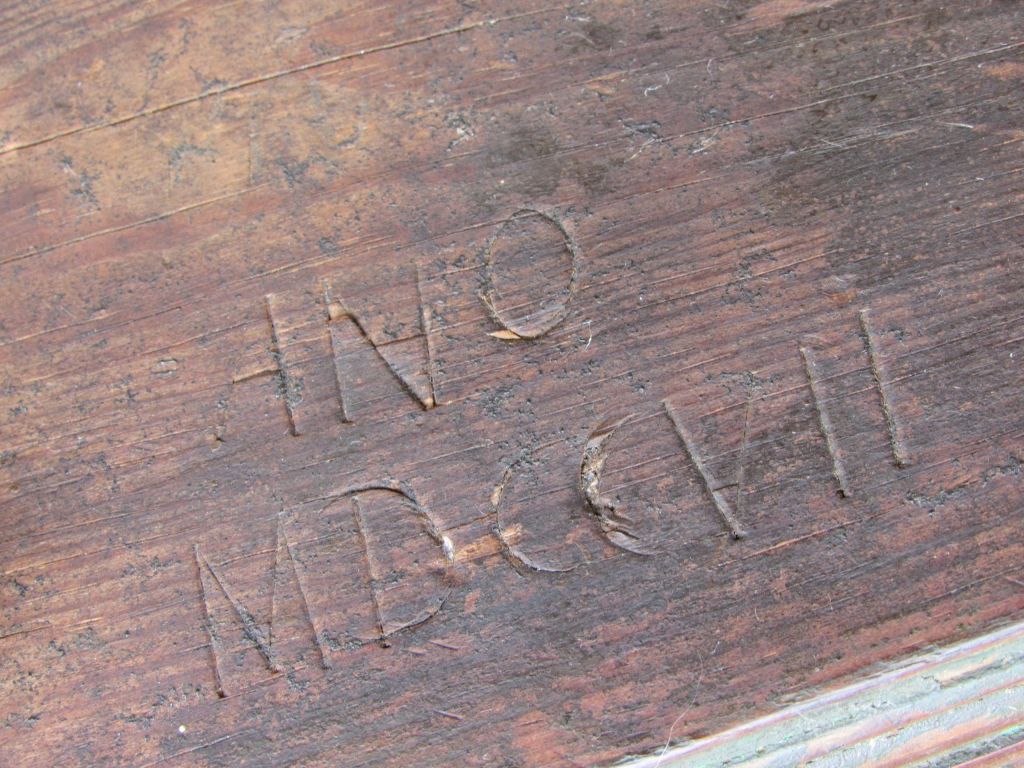

I know little about the history of this stately wheel. A woman in southern Maine kindly gave it to me. She had bought it from a woman–not a spinner–who decided to sell it because it was taking up space on her porch. How and when this wheel made its way to New England likely will remain a mystery.

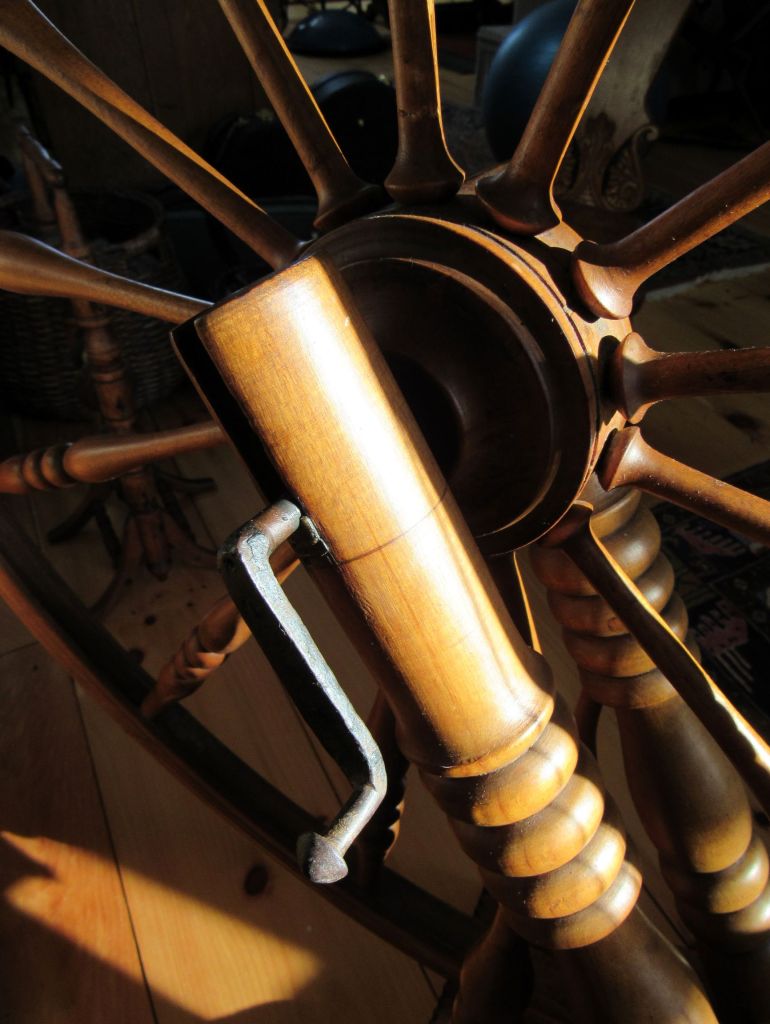

It almost certainly came from Ireland originally. It has the distinctive characteristics of an Irish wheel of this style–upright stance,

a drive wheel that sits close to the flyer but high off the table,

thick, solid legs,

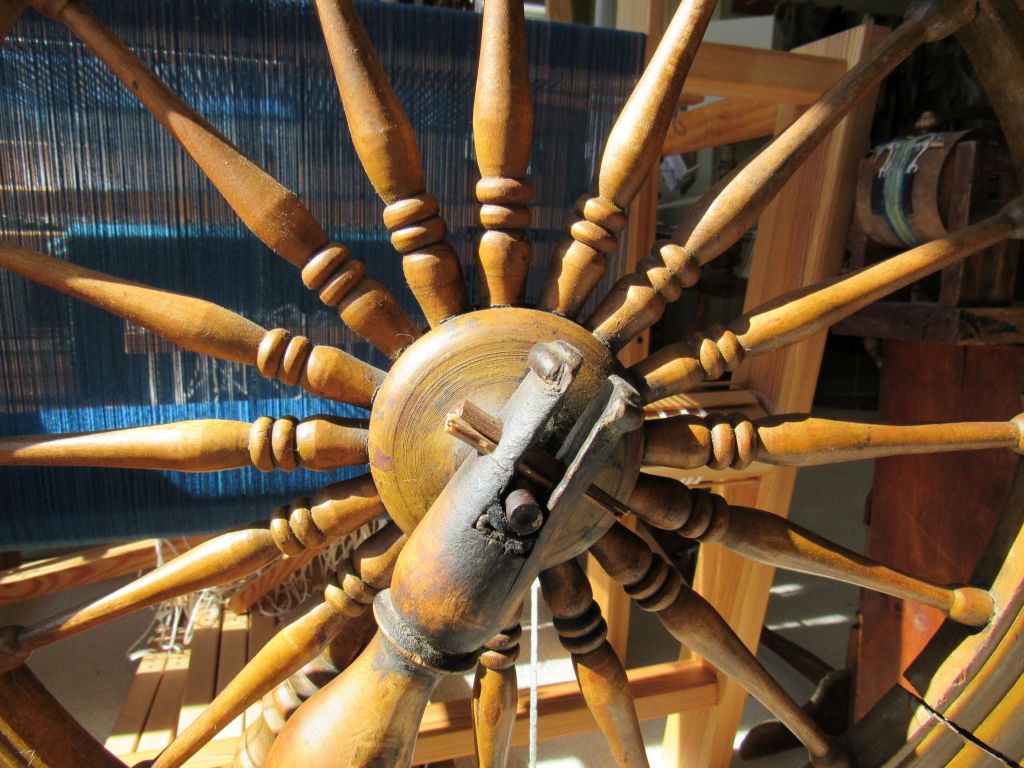

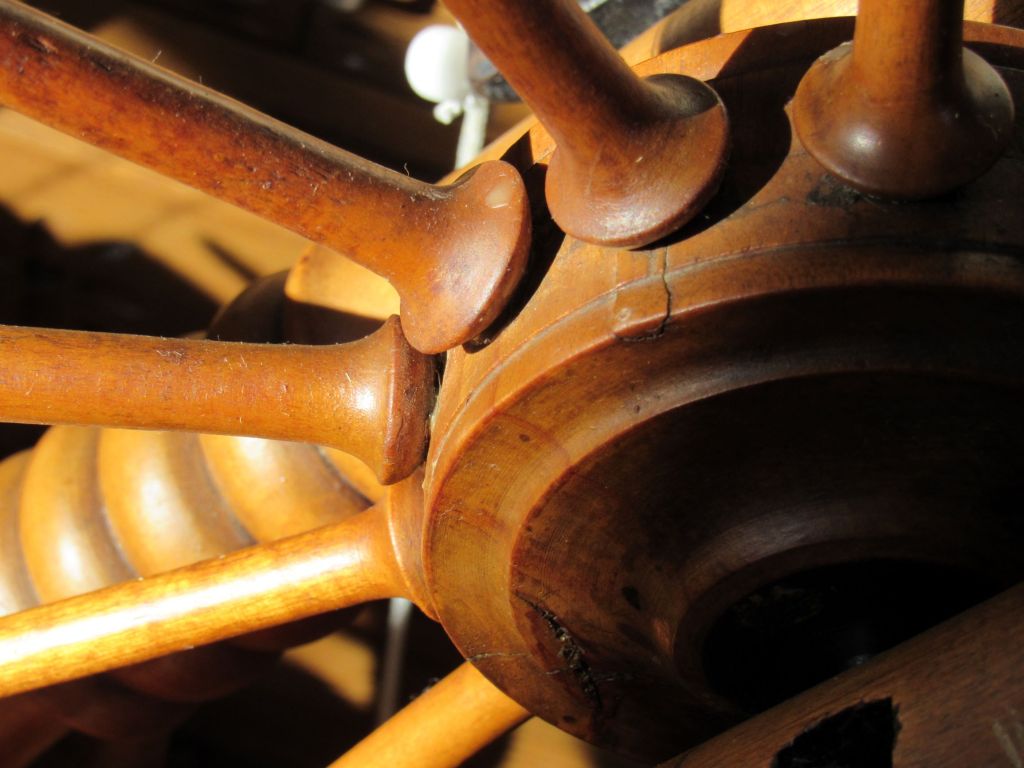

and amazing reed turnings, row upon row of tiny ridges that look like perfect smocking.

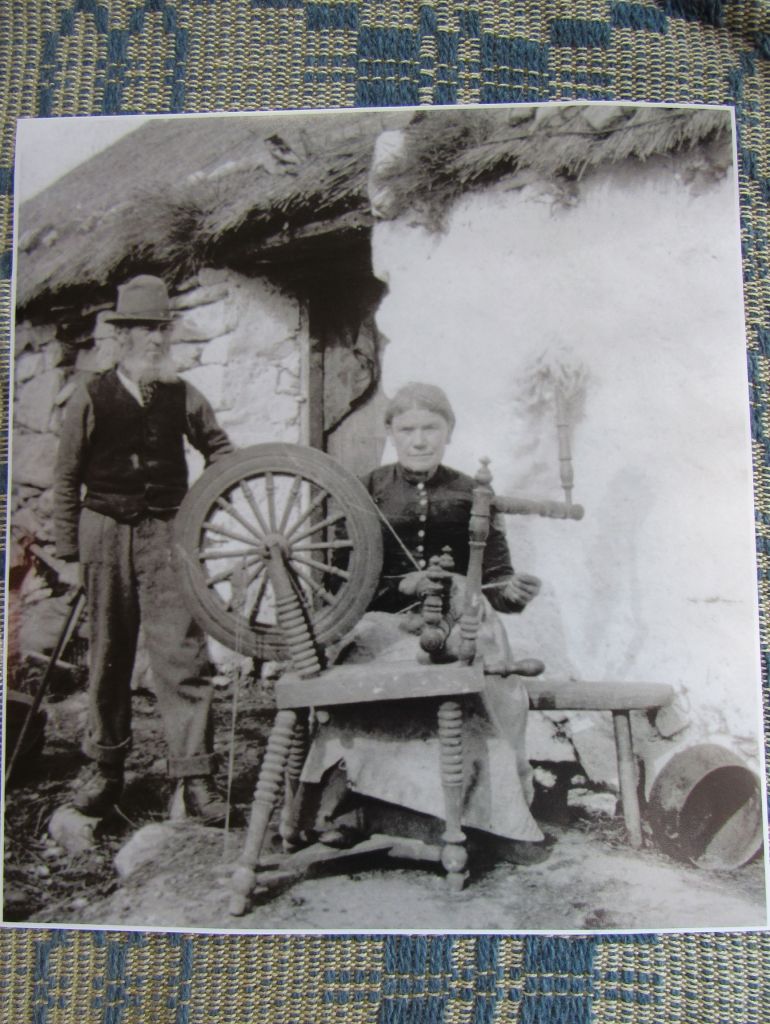

Old postcards and photographs show a variety of similar wheels being used in Ireland.

Interestingly, in these photographs, most of the footmen are string or cord (usually with a leather piece attaching to the axle) rather than wood, a contrast with North American wheels.

When starting to research this wheel, I posted a photograph on Instagram. Fortunately, Johnny Shiels, a third-generation wheel maker in Donegal, saw the photo and thoughtfully reached out. He sent me a photo of a very similar antique wheel from Donegal. And, his IG account spinningwheels.ie revealed photos of other lovely old Donegal wheels that he has restored.

This style wheel, which we usually refer to as a “Saxony” in North America, is known in Ireland as a “Low Irish” or “Dutch wheel.” Actually, early Connecticut probate records from the 18th and early 19th century often referred to them as Dutch wheels, too. These wheels were introduced to Ireland from Holland by Thomas Wentworth, later the Earl of Stafford, in the 17th century to encourage linen production.

While originally intended for flax spinning, they later also would be used for spinning wool.

Ireland also had spindle-style great wheels, often called “long wheels” for wool spinning. The wheel style that we, in this country, most often associate with Irish flax spinning, however, is the upright “castle” wheel. I have been curious as to whether the different styles were regional.

Were castle wheels and Dutch wheels both used throughout Ireland, or were they exclusive to different areas? And, were the turnings on the Dutch wheels specific to certain towns or counties?

The only information I have found so far is in the booklet from the Ulster Museum, which indicates that castle wheels were principally found in Ulster, explaining that they were “confined in distribution to the northern counties. The design provides good rigidity which is essential to efficient spinning.” Id.

The same stability applies to Handsome Molly, but derives from sheer size and weight. It is a remarkably large wheel, with long legs of substantial girth, and a wide heavy table.

It measures 43 1/2 inches tall, with an orifice height of 29 1/2 inches. The table is an ample 7 1/4 inches wide and upright circumference is 8 1/4 inches.

For comparison, it is almost a full foot taller than a typical Connecticut flax wheel made by Silas Barnum.

The legs on the Barnum wheel look puny compared to Molly’s generous proportions.

There is something about the sheer mass of this wheel that does affect spinning–giving a certain lightness and ease. Pure pleasure. There are signs of use on the wheel, but it is difficult to tell how much.

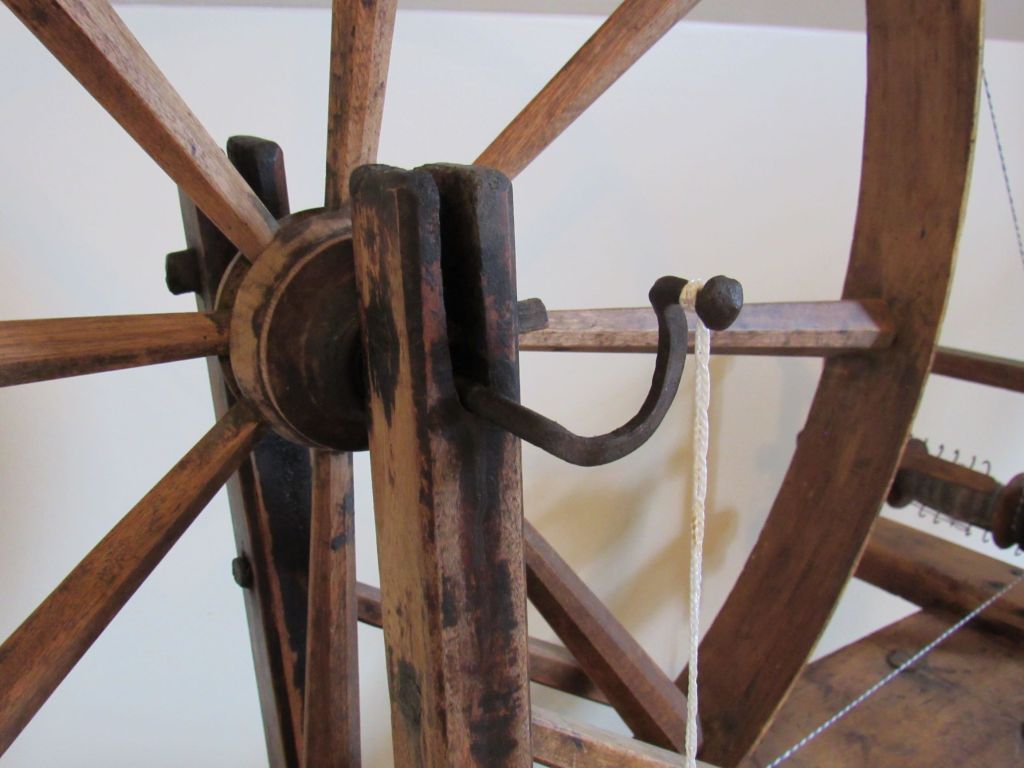

There are grease marks around the axles and some signs of treadle wear.

There appear to be some wear marks, from winding off perhaps, on the tension knob. The groove over the fat part of the knob looks just like the puzzling groove on the wheel Adelaide’s knob in a previous post.

Both maidens are pegged through the mother-of-all and do not turn.

They are in good condition and look much like the maidens on Green Linnet, in a previous post.

The distaff is made from a tree branch, typically used for spinning tow.

The distaff cross-support threads into the upright.

That is a feature I have never seen before, but brilliant to keep the distaff full of flax from tipping over while spinning (which it can do–I speak from experience).

The cross support also has what appear to be wear marks from thread or yarn, again, perhaps from winding off.

There are secondary upright supports on both sides, extending to the table.

Decorative marks ring the uprights and legs, both burned and incised.

The wood grain is interesting, somewhat wide and coarse

–perhaps oak, ash or a mix?

I do not have the original flyer yet. It still exists, but has been stored away and the hunt is on to find it. I am hoping that it will give more clues as to whether this wheel was brought to this country for use or for decoration. It cannot have been easy or cheap to transport across the Atlantic. But, I totally understand why someone would go to the trouble, because it is a magnificent piece of machinery.

I am extremely grateful that this wheel is now taking up space in my home. And, it is not relegated to the porch, but in a place of honor, creating beautiful yarn.

October 2021 update: Joan Cummer had a somewhat similar wheel in her collection, Wheel No. 30. In describing the wheel, she notes: “This wheel was made in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century in Ireland. The turnings are Sheraton period with extremely fine reed turnings on the distaff … This has been a well made and very heavy wheel.” Cummer, Joan Whittaker, A Book of Spinning Wheels, Peter E. Randall, Portsmouth, NH, 1994 (pp. 72-73).

For more information see:

Johnny Shiels Inishowen Spinning Wheels, website here.

Evans, Nancy Goyne, American Windsor Furniture, Hudson Hills Press, New York, NY, 1997 (p. 214).

Ulster Museum, Spinning Wheels (The John Horner Collection); Ulster Museum, Belfast, Ireland 1976.