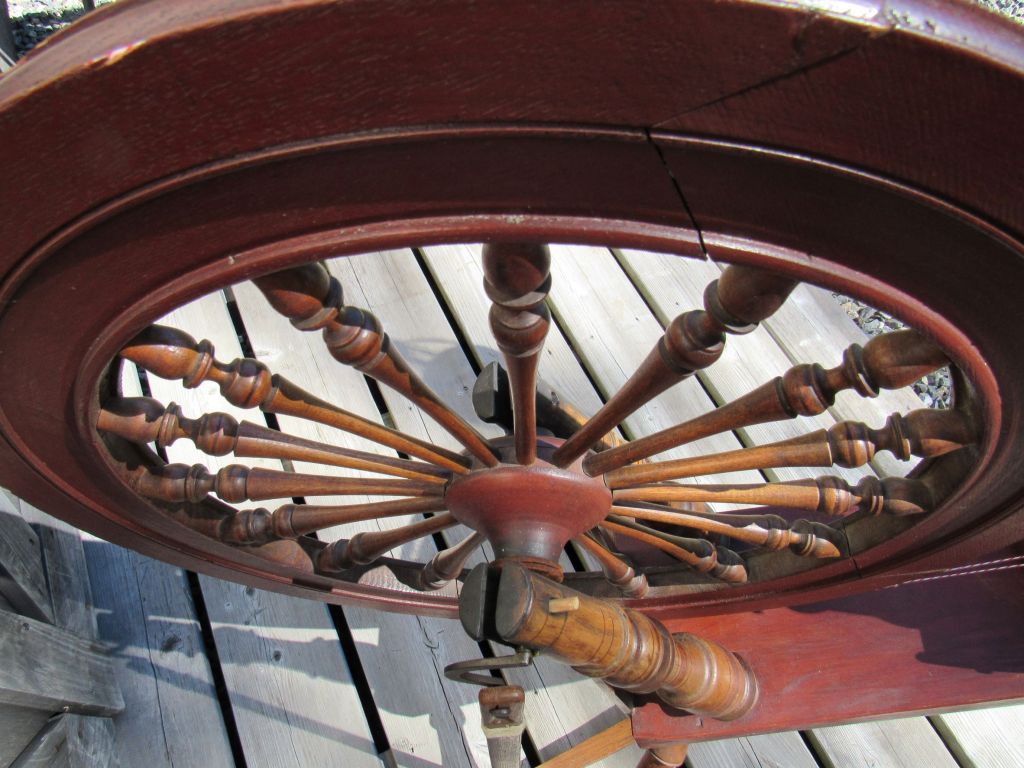

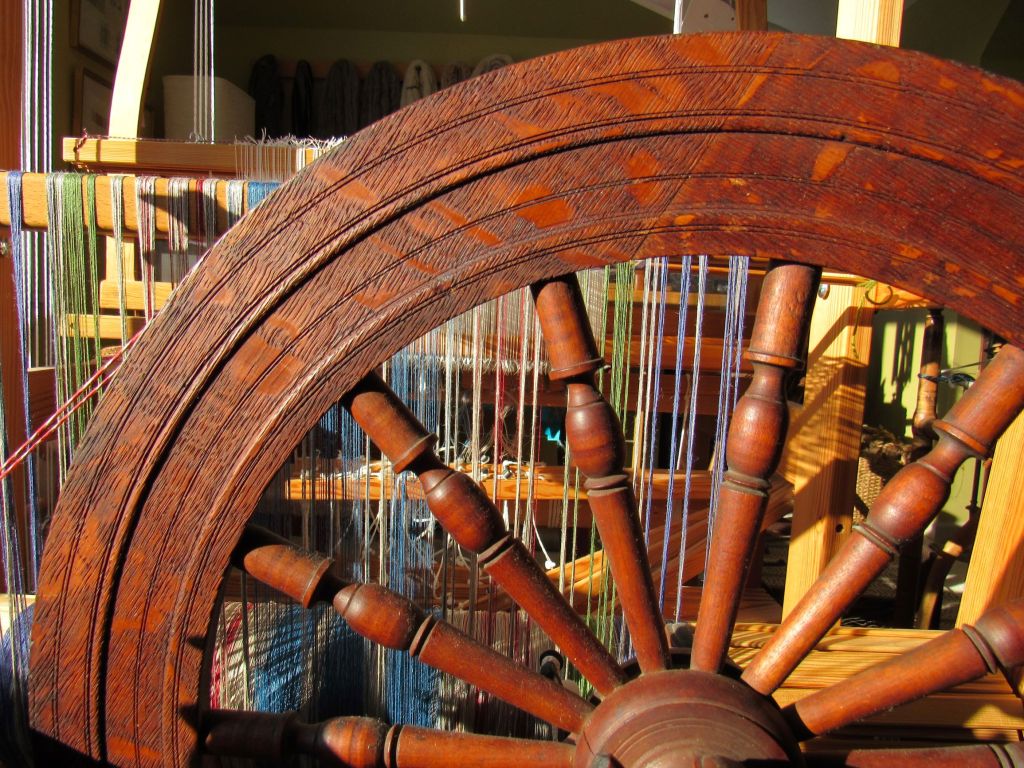

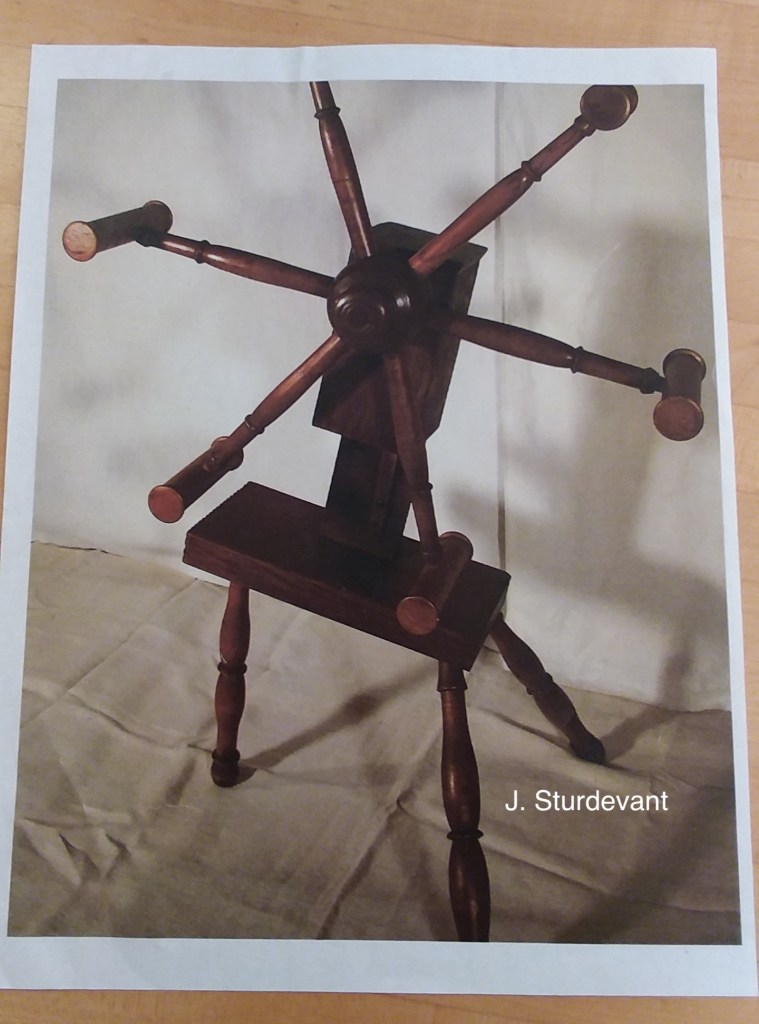

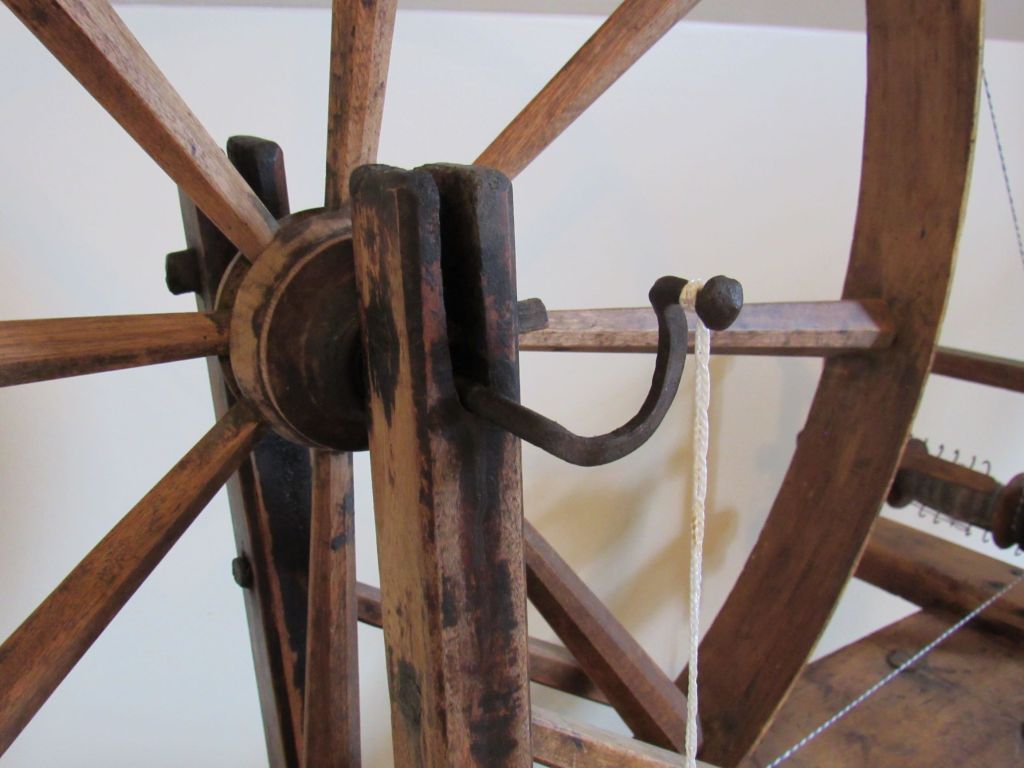

This New England wheel is a striking contrast to Scarlet, the wheel in the previous post. Although both wheels likely were made in Vermont, they represent two ends of the decorative spectrum. While Scarlet flaunts her beauty, with ornate turnings from spokes to legs, Jocasta is spare, with sleek lines and only subtle touches of adornment.

Like many northern New England wheels, Jocasta shows the influence of the area’s Shakers, whose wheels popularized simple turnings and clean lines. (see previous post “Patience”)

Beginning in the 1790s, the Shakers manufactured thousands of wheels at their communities in New Hampshire and in southern Maine. Many non-Shaker wheel makers nearby were influenced by the understated Shaker style. Traditional turnings in the Scottish or German style became toned down and smoothed out. Jocasta is a good example of that transition, with very Shaker-like lines, but retaining remnants of a Scottish heritage.

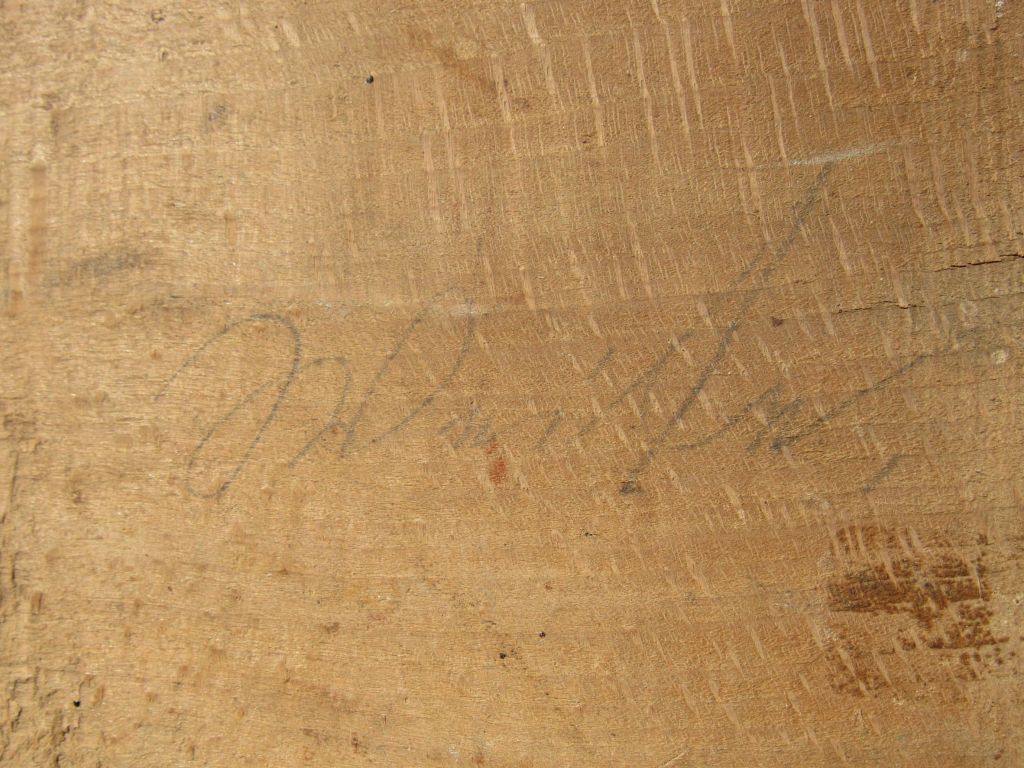

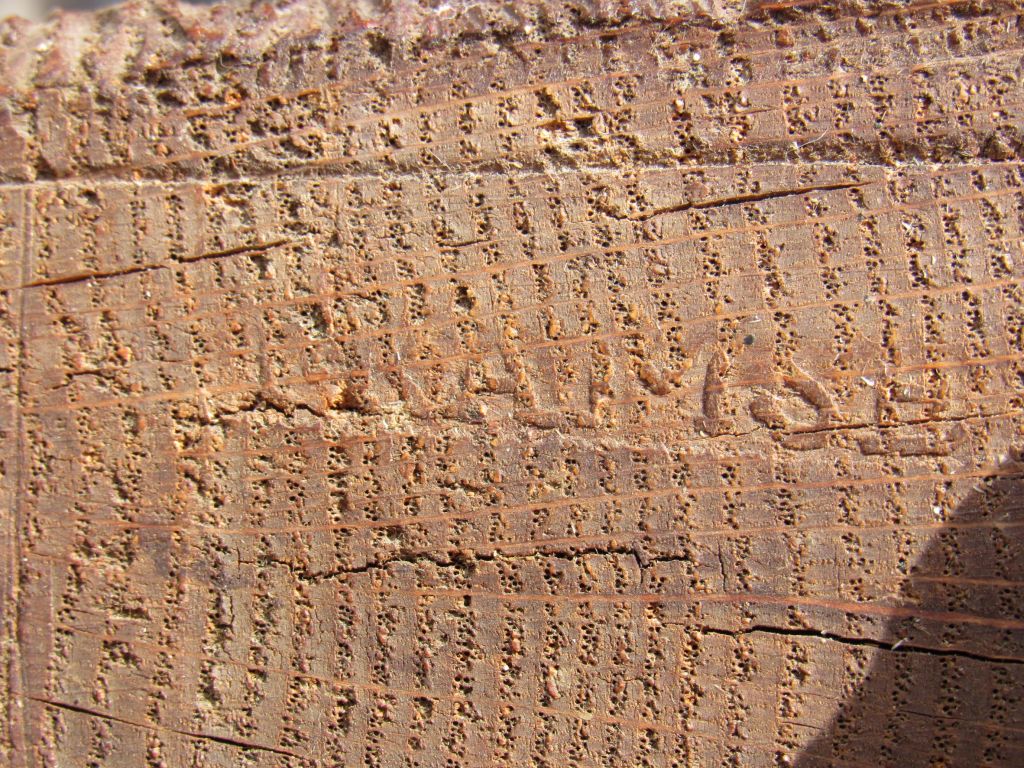

I bought Jocasta several years ago at an antique mall in Searsport, Maine, intrigued by her faint maker’s mark. Mostly worn off and very hard to see under the store’s dim lights, it was not a mark that I recognized. Looking closer when I brought her home, I thought the mark might be “Ramsey.”

I was familiar with wheel maker Hugh Ramsey, from Holderness, New Hampshire (1754-1831). His father, James, lived in Londonderry, New Hampshire, a town settled by Scots-Irish who developed it into an early center of New England linen production. (Feldman-Wood pp. 4-5) Londonderry had numerous wheel makers, including the Gregg brothers, Daniel Miltimore, John Ferguson, and James Anderson (who, with his brothers, later founded the Shaker Alfred Lake spinning wheel business). (Taylor pp. 2-4) The Londonderry wheels, some made as early as the 1750s and 60s, usually were 16-spoked and decoratively turned into heavy curves in the Scottish tradition. (Taylor p. 3) Hugh Ramsey’s wheels retained the basic style of the Londonderry wheels, but his turnings were less ornate.

Not as clean and spare as Jocasta, but moving in that direction. He did not sign his wheels with “Ramsey,” but rather his initials, “HR.” (Feldman-Wood p. 5)

While it was apparent that Jocasta was not made by Hugh Ramsey, I wondered if the maker might be related to him.

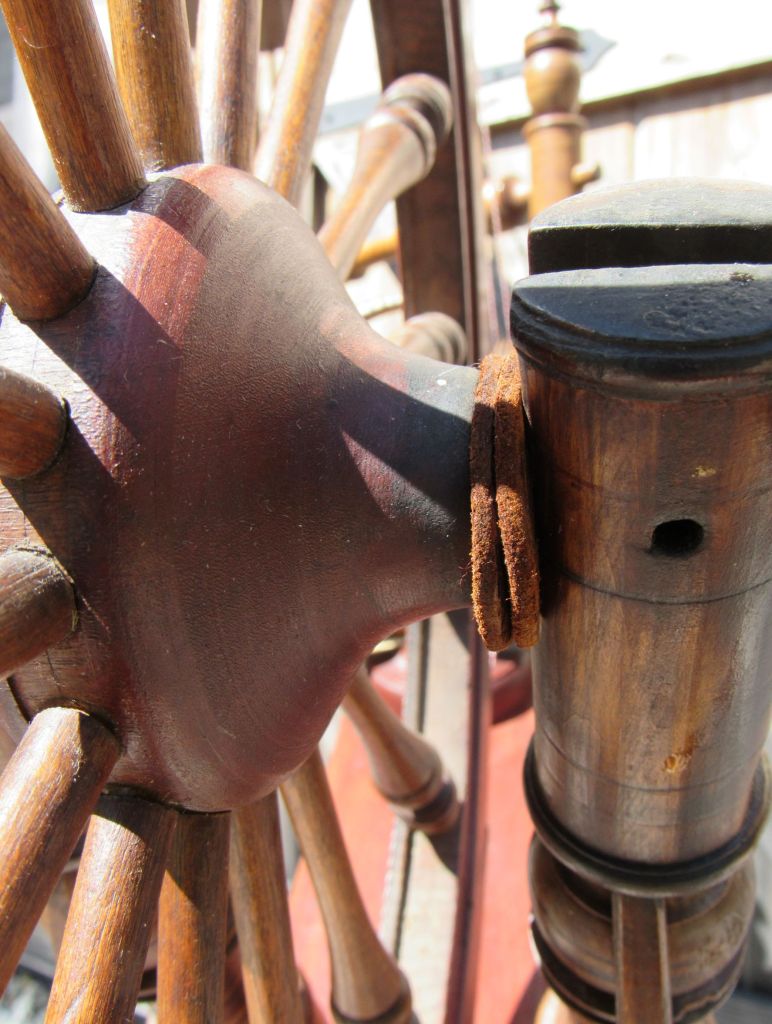

I first looked for a Londonderry connection because Jocasta’s maidens resemble some of those on the Londonderry wheels. Could Hugh’s father, James, have other wheel-making sons?

I did some quick research and did not find any obvious wheel makers among Hugh’s many brothers. Research was complicated by the fact that the family spelled their name as “Ramsey” or “Ramsay” with no apparent pattern.

I abandoned the research for another day, which came about a year later, when I noticed Jocasta’s twin in the book of Joan Cummer’s wheel collection. It is wheel No. 59 in Cummer’s book, described as 18th or early 19th century and “a typical New Hampshire wheel of that time.” (Cummer pp. 134-35) Like Jocasta, it was marked “Ramsey.” Cummer’s Ramsey wheel was donated to the American Textile History Museum and put up for auction after the museum closed. Fortunately, we have some photos of it from that auction.

Unfortunately, I do not know who bought it. I also found that Cummer’s wheel is referenced under wheel maker William Ramsey in Pennington & Taylor’s wheel maker list. (Pennington & Taylor Appendix) I did a quick online search on William Ramsey, found nothing helpful, and left it at that.

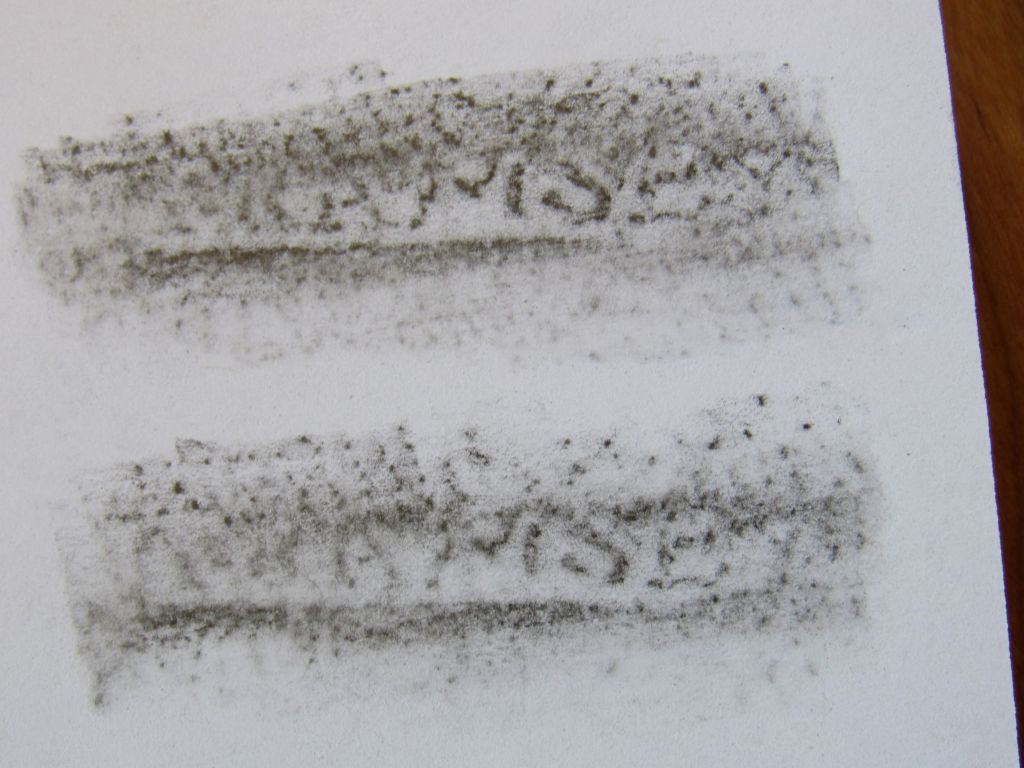

My sporadic, unproductive research was given a jump-start, however, when, a few months later, Gina Gerhard posted a James Ramsey great wheel on Facebook, with a photograph of the maker’s mark.

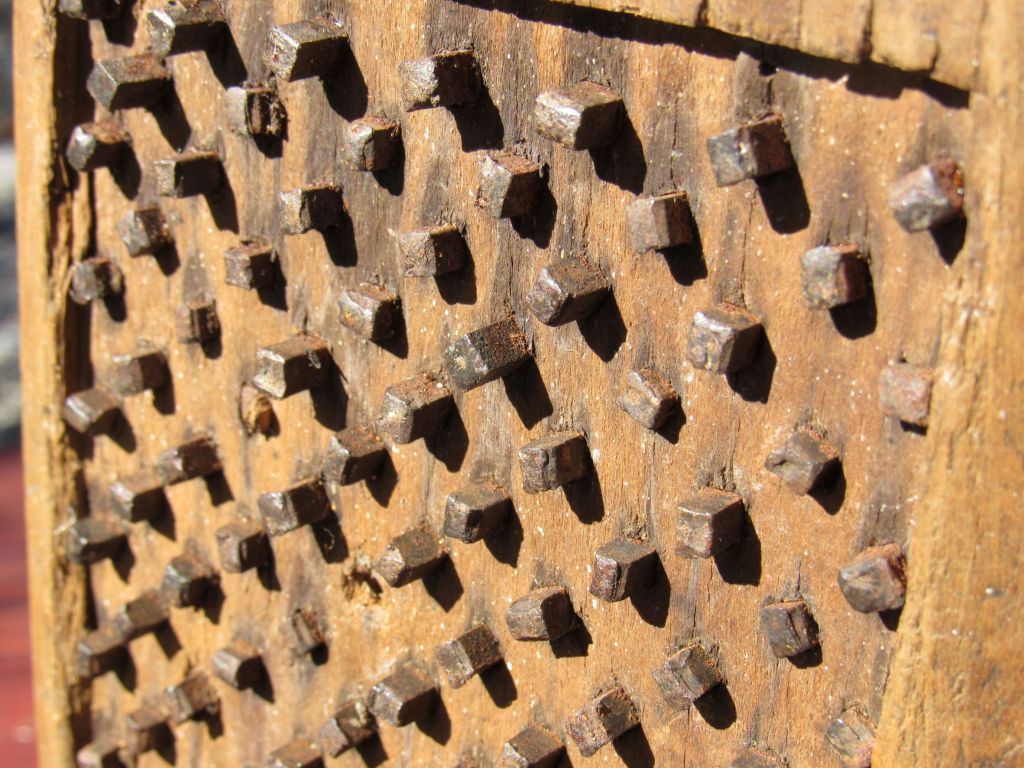

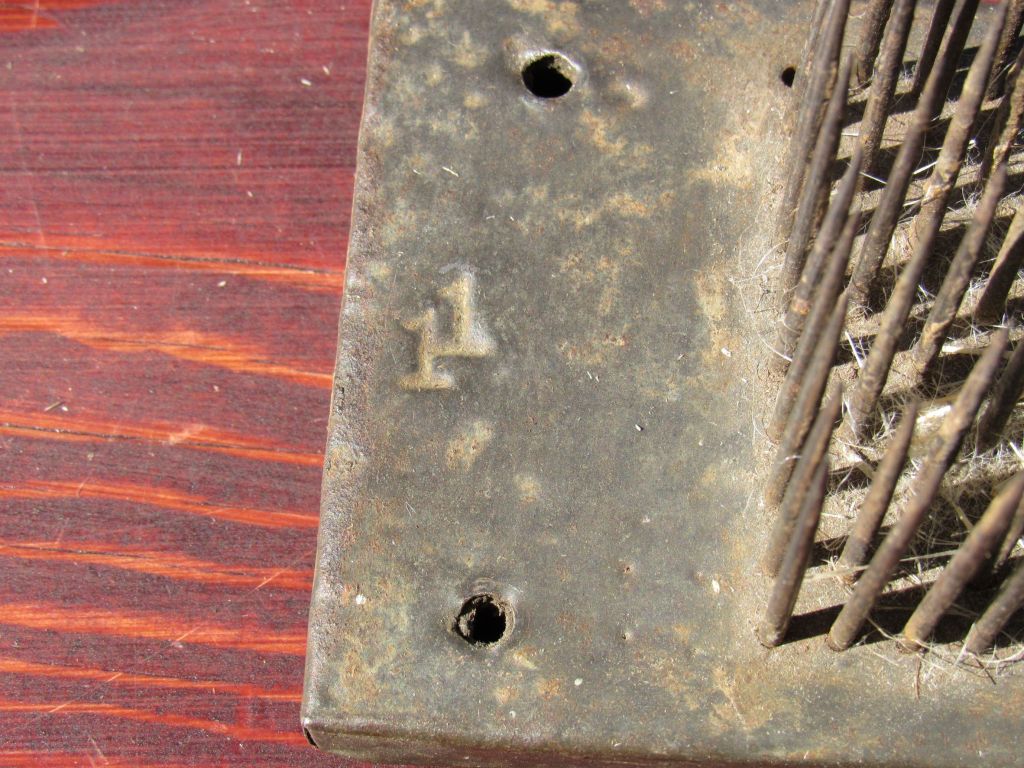

Although the mark is worn on Jocasta,

what is left appears to be the same as the mark on Gina’s wheel, even down to the little bobble on the tail of the letter “S.” But the first letter is almost completely worn off of Jocasta.

I think I can see an “I” with one of the double dots, as on Gina’s wheel. But it is hard to be sure.

To compound the puzzle, around this time, collector Craig Evans sent me a photo of a wheel that looks much like Jocasta, but marked with “JR.”

Could James Ramsey have changed stamps at some point? Was there another J. Ramsey wheel maker in the family—or a different JR altogether?

At this point, I wanted to find a confirmed James Ramsey flax wheel. He was from St. Johnsbury, Vermont, so I wrote to their History & Heritage Center, but did not get a response. For the third time, I abandoned the research—this time for about a year.

I took it up again last month when I decided to do this blog post.

Both Gina and Craig mentioned that wheel collector, Sue Burns, had donated a James Ramsey wheel to the Fairbanks Museum in St. Johnsbury. I wrote to the museum and found that they had disbanded their wheel collection and had given the Ramsey wheel to one of three other museums, most likely the St. Johnsbury History & Heritage Center.

So, I wrote to the History Center again, and this time immediately got a response. It turns out that the only Ramsey wheel donated by Sue Burns was a great wheel, not a flax wheel.

Without seeing a confirmed James Ramsey flax, I cannot be sure that this wheel was made by him. Nevertheless, given what we can see of the maker’s mark, it appears very likely that Jocasta was made by James Ramsey.

Edward Fairbanks’ 1914 history of St. Johnsbury provides an interesting portrait of James Ramsey. He came to St. Johnsbury in 1817, where he took over a previously built grist mill.

“Ramsey was a character, a large, bony Scotchman, with a fund of droll stories which he delighted to tell to the neighbors and over which he would shake with honest laughter.” (Fairbanks p. 146)

Ramsey settled his family near the mill, set up a carding machine in the home and, in 1820, with a partner, also built a sawmill.

James Ramsey had served in the war of 1812, with the rank of Captain. “Cap’t Ramsey as time went on built a new house. He became a stiff anti-slavery man and his house was one of the underground railway stations, so called, where runaway slaves were taken in and helped on their way to Canada” (Fairbanks pp. 146-47)

During demolition of the home in the 1930s, a second windowless cellar was discovered under the regular cellar—an underground railroad stop that actually was underground. (Caledonian Record article).

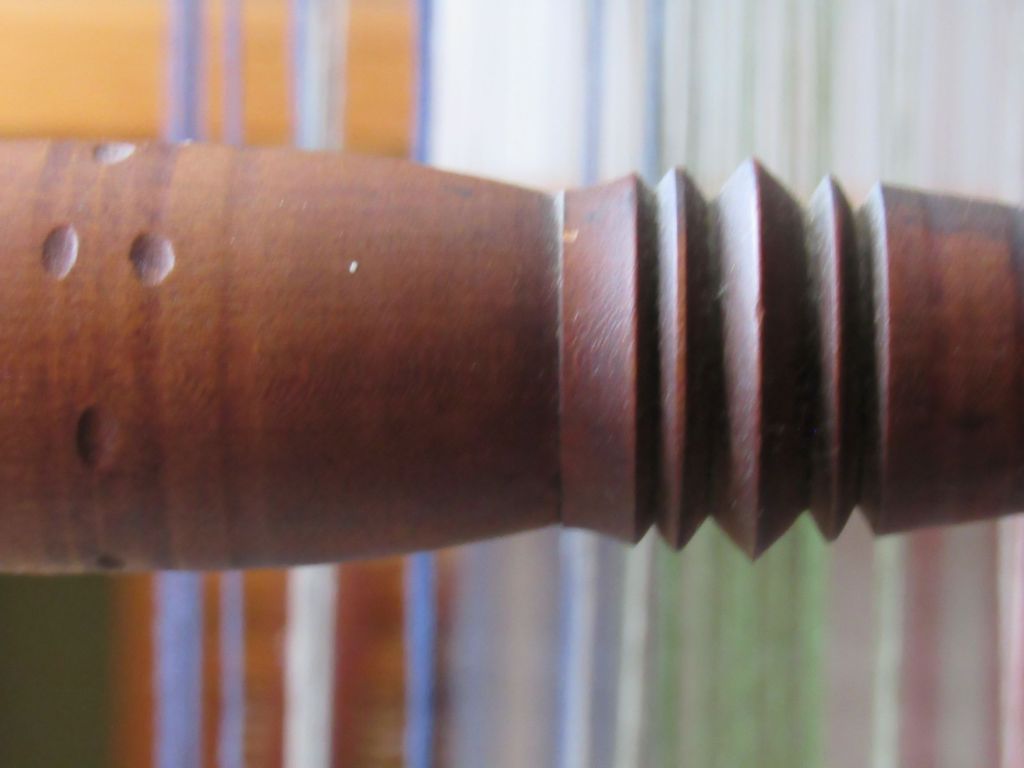

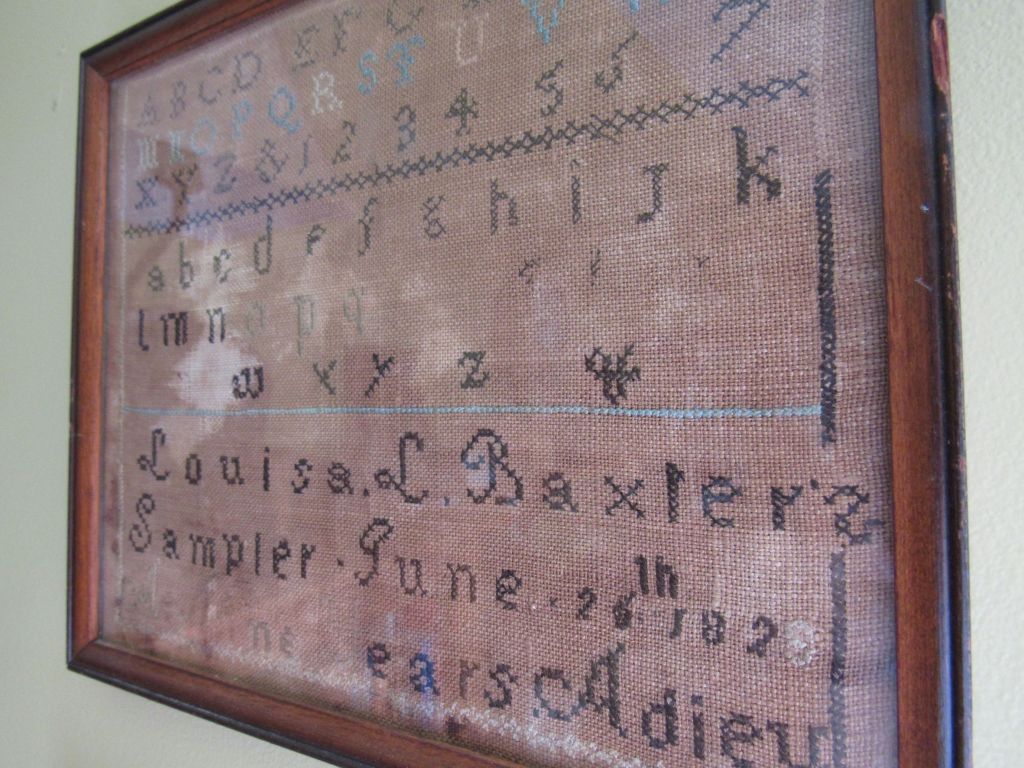

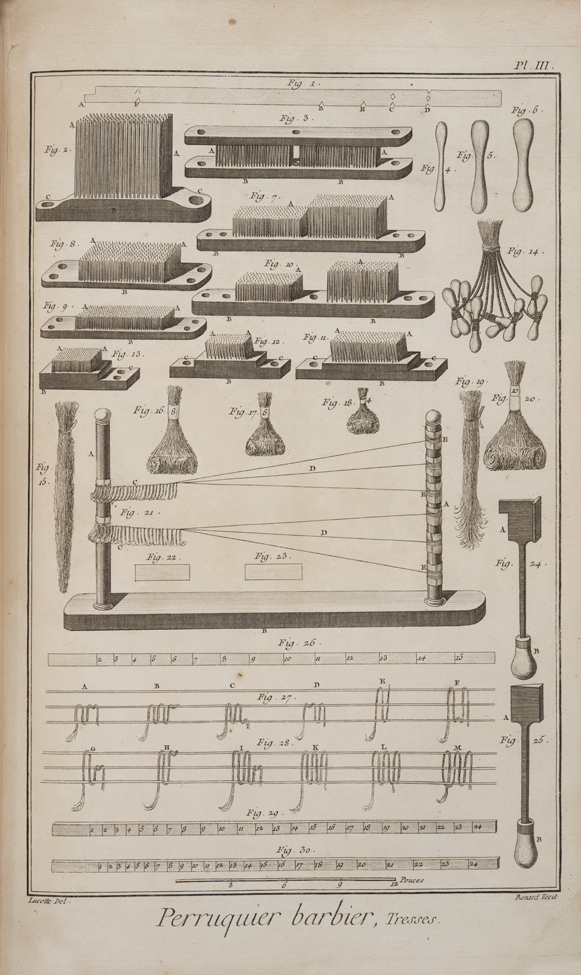

“Ramsey also became a spinning wheel manufacturer; his wheels for spinning domestic flax were considered a superior product; with oil stained red rims and cranks and spindles of best hard Swede stock.” (Fairbanks pp. 146-47) His advertisement shows the range of his products:

“Improved Patent Accelerating Wheel Head $1.13 each–Manufactured by James Ramsay–Cast Steel Set in Brass–Will Require Frequent Oiling–Spinning Wheels of every kind; Quilling Wheels, reels, shuttles,–And Spools may be had at the –Shop in St. Johnsbury, Caledonia County, Vermont–All warranted good or no sale.” (Caledonian Record article)

James died in 1860 in St. Johnsbury before seeing his youngest son, John, die in the Civil War in 1862.

This glimpse into Ramsey’s life and personality made me even more curious as to where he came from and whether he was related to Hugh Ramsey. So, I took another stab at genealogical research on ancestry.com and this time hit pay dirt. According to several family trees, Hugh Ramsey was born in Londonderry, New Hampshire, to parents James and Elizabeth, alongside twelve other children.

Hugh had seven brothers, named John, Robert, David, James Jr., Matthew, William, and Jonathan. Hugh’s brother William (1750-1823), like Hugh, left Londonderry, and by 1800 or so was living in Vermont.

William’s second son, James, was born in Londonderry in 1778, married Hepzibah Crossfield in 1805 in Surry, Vermont, and by 1817 moved to St. Johnsbury, where he and Hebzibah eventually had eight children and he made spinning wheels. So, it turns out that James, our St. Johnsbury wheel maker, is Hugh Ramsey’s nephew.

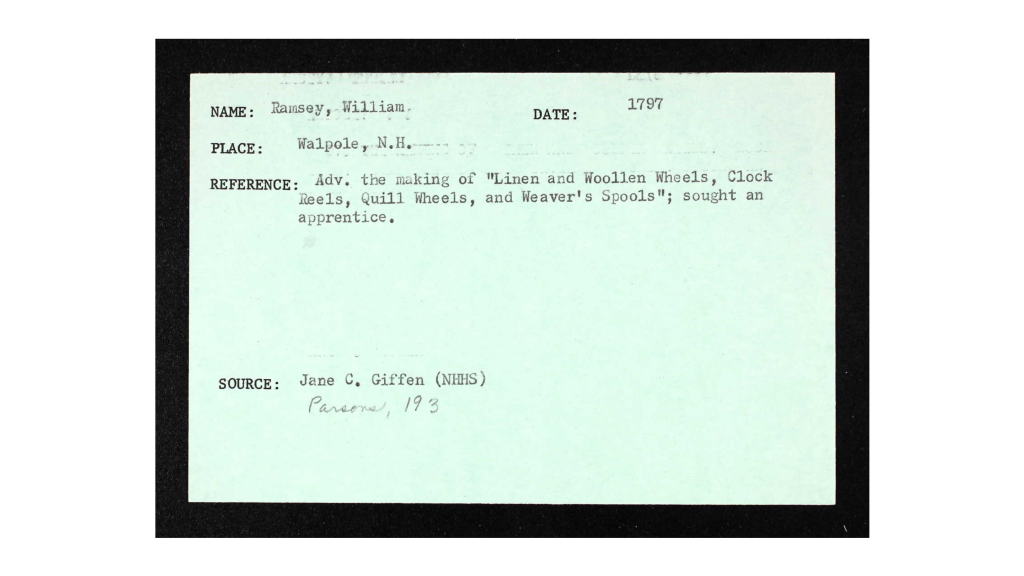

Interestingly, one genealogy showed James’ father, William, making spinning wheels in Walpole, New Hampshire, based on a listing in the U. S. Craftsperson files, which cited a 1797 advertisement selling wheels and seeking an apprentice.

I have not been able to find any other evidence, however, that this William (James’ father) lived in Walpole, although it’s certainly possible.

It is also possible that it was James’ brother, not his father, who made wheels in Walpole because The History of Walpole’s genealogy section lists William Ramsey, “wheelwright,” his wife, Elizabeth Hibbard, and their two oldest children as residents. (Frizzell vol II, p. 237).

The William who married Elizabeth Hibbard was James’ brother, born in 1782. If the 1797 date is accurate in the Craftsperson files, he would have been only 15 or 16 at the time, which seems quite young to setting up business and seeking an apprentice.

So, my on-again, off-again research sparked by one flax wheel with a worn maker’s mark continues. More research is needed to confirm that Jocasta was made by James Ramsey, to determine which William was making wheels in Walpole, and to figure out how the JR marked wheels fit into the picture.

While wheel maker research never seems to be completed—each discovery reveals new paths and wrinkles to explore–it also turns up unexpected treasures, such as this fascinating excerpt from the 1914 History of St. Johnsbury:

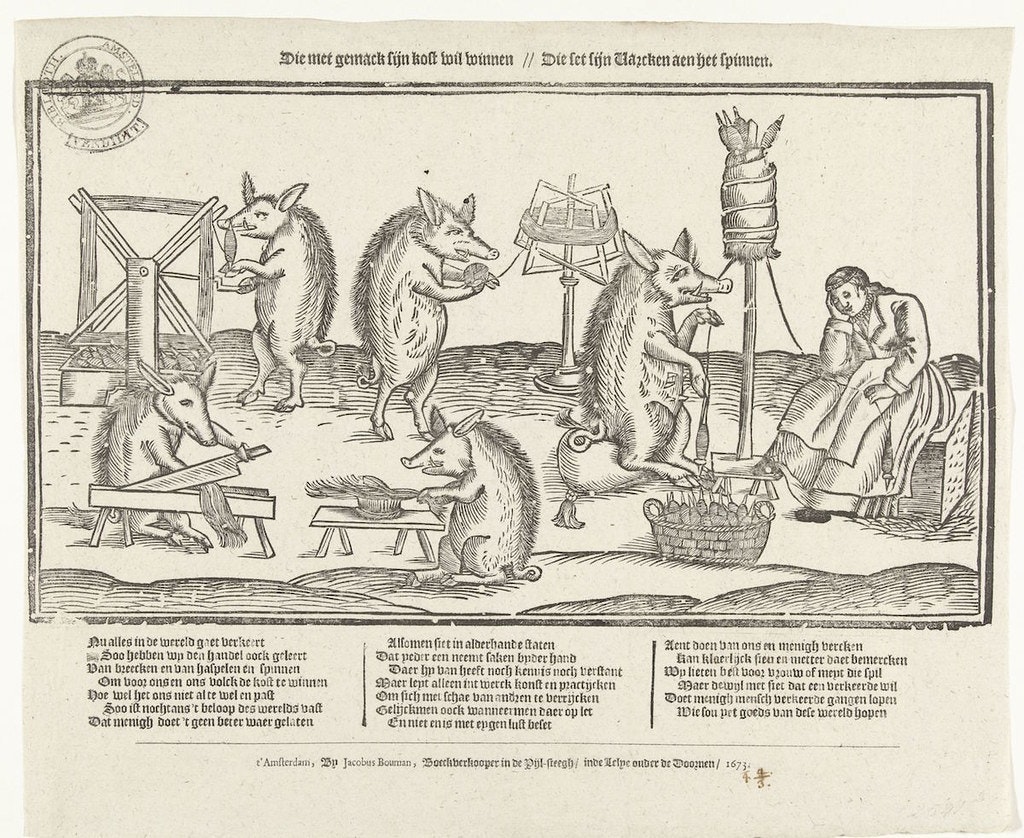

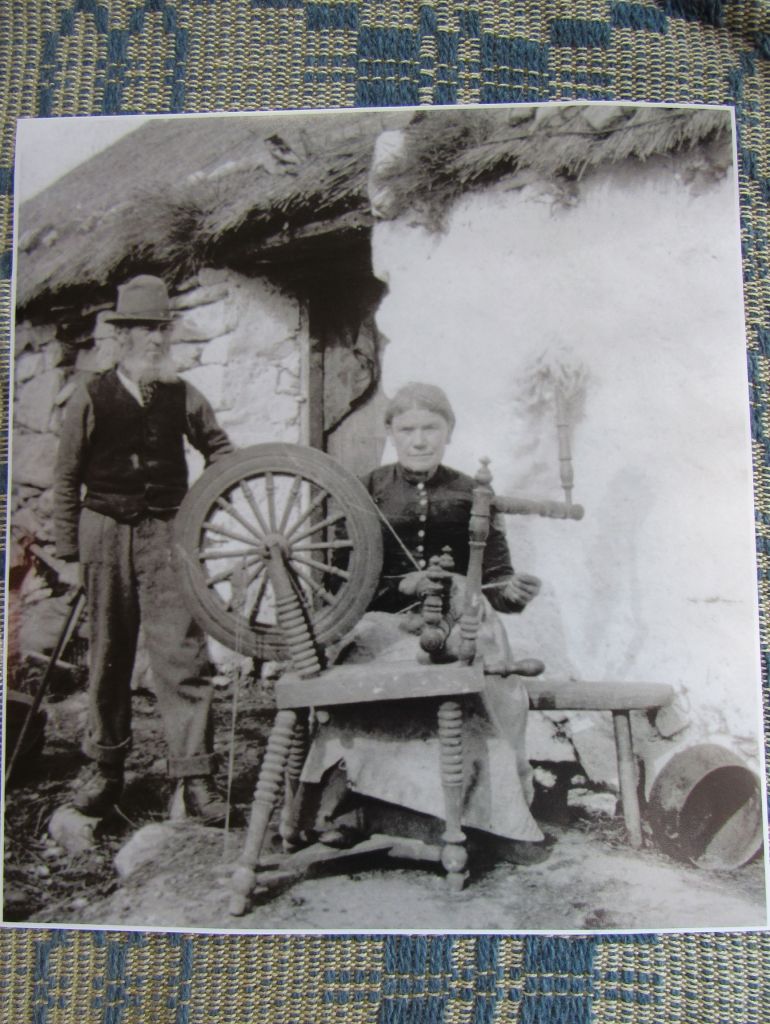

“Spinning and Weaving

These were necessary accomplishments in the department of woman’s industry. As soon as wool and flax could be raised on the clearings the spinning wheel was started and later the loom, and all the clothing of the settlement was of homespun made in the family kitchens. After 1800 nearly every well to do family would have either wheel or loom or both, the girls became skilled spinners and the mothers wrought firmly woven fabrics on their heavy looms.

An average day’s work would be to card and spin four skeins of seven knots each, forty threads to a knot, two yards in length. Flax spun on the little wheel would be two double skeins of fourteen knots each. When enough was spun for a web of twenty yards it was boiled out in ashes and water and well washed; then spooled and warped ready to weave into cloth, for various garments. Table cloths and towels were woven in figures, dress goods from flax, colored and woven in checks.

The volume to which this family industry attained is expressed in the returns given for the year 1810. During that year, the women of St. Johnsbury turned off from their looms 16,505 yards of linen cloth, 9,431yards of woolen, 1797 yards of cotton cloth. A total of 27,733 yards.” (Fairbanks pp. 138-39) “After some years [in the 1820s and 30s] mills began to be set up in different parts of the town [for dressed cloth] … Many of the women however continued to manufacture their own cloth.” (Fairbanks pp. 139-140)

With such a large volume of spinning, it is no wonder that so many antique wheels bear marks of heavy wear. Jocasta was well used

and has been one of the very best wheels for spinning fine flax in my flock.

If anyone has more information on James Ramsey and his wheels, please let me know.

Thank you to Craig Evans (JR wheel), Gina Gerhard (Ramsey great wheel), and Krysten Morganti (Cummer wheel and Hugh Ramsey wheel) for allowing me to use their photographs. Also, thanks to Gina for her research on James Ramsey.

The Fairbanks Museum & Planetarium in St. Johnsbury, the St. Johnsbury History & Heritage Center, and the Old Stone House Museum & Historical Village all helped in my attempt to locate a confirmed James Ramsey wheel. I am very appreciative that they took the time to respond to my questions.

Edited to add on November 17, 2022: After I posted this, Vermont weaver, Justin Squizzero (The Burroughs Garret), sent me photos (below) of one of his wheels, which is unmarked and from a Vermont collector. While it has some minor differences from Jocasta and Craig’s “JR” wheel, it has some remarkable similarities. The legs, in particular, have the same turnings at the “ankles” and it has similar grooves down the sides of the table top. Those particular features set these three wheels apart from Shaker wheels, which have smooth legs and tables. Notably, the S. Cheney wheels also share the ankle turnings and table grooves (see previous post “Sweet Cicely and Chancey”). So, while these particular wheels at first glance almost appear to be Shaker wheels, they all share the same deviations from Shaker wheel design. That suggests some connection between these three wheels. Were they made by the same person at different times, by related wheel makers, or was there some geographical market influence over the non-quite-Shaker style? Fascinating. Thanks Justin.

References:

Feldman-Wood, Florence, “Hugh Ramsey, Spinning Wheel Maker,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue $48, April 2005, pp. 4-5.

Taylor, Michael, “Londonderry, NH, Flax Wheels,” The Spinning Wheel Sleuth, Issue #48, April 2005, pp. 2-4.

St. Johnsbury History & Heritage Center, Caledonian Record newspaper, February 1, 2012.

Merrimack Valley Textile Museum, All Sorts of Good Sufficient Cloth: Linen-Making in New England 1640-1860, Merrimac Valley Textile Museum, North Andover, Mass., 1980.

Cummer, Joan, A Book of Spinning Wheels, Peter E. Randall, Portsmouth, N.H. 1984.

Fairbanks, Edward, The Town of St. Johnsbury Vermont, The Cowles Press, St. Johnsbury, VT 1914.

Frizzell, Martha McDanolds, A History of Walpole, New Hampshire, Vol. II, Vermont Printing Co. 1963.

Pennington, David & Taylor, Michael, Spinning Wheels & Accessories, Schiffer Publishing, Altglen, PA, 2004.

Ancestry.com for research on Ramsey genealogy